Elite court painters of the Joseon Dynasty produced colorful works filled with wishes for the longevity of the king and the royal family. Their labor appeared on wide canvases, folding screens, hanging scrolls, and wall paintings.

“White Cranes.” Kim Eun-ho. 1920. Color on silk. 214 × 578 cm.

This mural is found inside Changdeok Palace on the western wall of Daejojeon, the queen's chambers. It was painted by Kim Eun-ho (1892–1979). His work inherits traditional royal court decorative paintings, which feature splendid colors and delicate brushstrokes.

© National Palace Museum of Korea

The palaces of the Joseon Dynasty overflowed with color. The walls, pillars, and ceilings were decorated with dancheong, traditional paintwork coloring high-status buildings. Generous use of the primary colors — red, green, yellow, and blue — brought vibrant contrasts into halls and rooms and inspired the coloring of court ladies’ hanbok.

East Asian countries have similar but distinctly different color schemes. In China, yellow represents royalty and subdued colors are coordinated to emphasize solemnity. Japan leans toward subtle variations of many intermediate colors, such as violet, purple, and light green. In Korea, the complementary contrast between primary colors s a unique blend. The bright primary colors form the aesthetics of decorative artwork at the Joseon court that can still be viewed today.

Best Court Painters

“Picturesque Landscape of the Myriad Things on Mt. Geumgang.” Kim Gyu-jin. 1920. Color on silk. 205.1 × 883 cm.

Hung on the western wall of Huijeongdang, a hall at Changdeok Palace where the king presided over state affairs, this painting was d by the renowned painter-calligrapher Kim Gyu-jin (1868–1933) after he visited Mt. Geumgang. It follows the style and tradition of the Joseon Dynasty’s view of Mt. Geumgang and court decorative paintings. It also contains modern elements, including the painter’s seal, which had never been used before.

© Cultural Heritage Administration

The palace was no place for random artwork. Colors, motifs, and themes had to be formal in deference to the palace’s status as the residence of the royal family and the seat of national authority. Artists also had to be mindful of the great height and expanse of palace architecture. Thus, court paintings had to be much larger than the hanging scrolls and folding screens found in private houses.

The most talented painters in the country were recruited to work at the palace. Their workplace was Dohwaseo, the royal bureau of painting. It occupied the entrance of present-day Insa-dong, a traditional arts and crafts neighborhood near Gyeongbok and Changdeok palaces. The royal quarters were filled with the works of selected painters, who used liberal amounts of expensive paint.

Symbol of the King

“Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks.” Artist unknown. 1830s. Ink and pigment on silk. 219 × 195 cm.

This two-panel artwork symbolizes the King of Joseon. The decorative painting is believed to have been installed in Haminjeong, a pavilion at Changgyeong Palace, where the king received officials and held banquets.

© National Museum of Korea

A staple set piece frequently appearing in historical TV dramas is the “Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks” painting (Irwolobongdo) that was installed behind the throne in the palace’s main hall. The painting’s motifs are symbols expressing the idea that there is only one king and wishing for eternal life for the royal family. The sun and moon are incarnations of yin and yang and symbols of brightness. The five peaks represent the center of the Earth and correspond to the sky and the seat of the king, who is the Son of Heaven. The number five is significant, as it is the midpoint of the decimal system. Pine trees and waves are added for a perfectly symmetrical painting. The painters used refined pure mineral pigments, such as azurite for the sky, malachite for the peaks, and cinnabar for the pine trunks. Such magnificent colors and overwhelming images of the natural world were placed behind the king to elevate his authority.

The same composition was also painted on folding screens, placed behind the king when he was resting during travel, and in Binjeon, the hall where the king’s body was kept temporarily after death. Therefore, it was the most symbolic decorative artwork of the king’s reign. The two-panel painting that was presumably installed in Haminjeong, a pavilion at Changgyeong Palace, is one of the oldest among the many extant “Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks” paintings. The artist is unknown, but the true workmanship of a Dohwaseo painter is evident through the depiction of the subject in dignified form and meticulous coloring.

Universal Desire

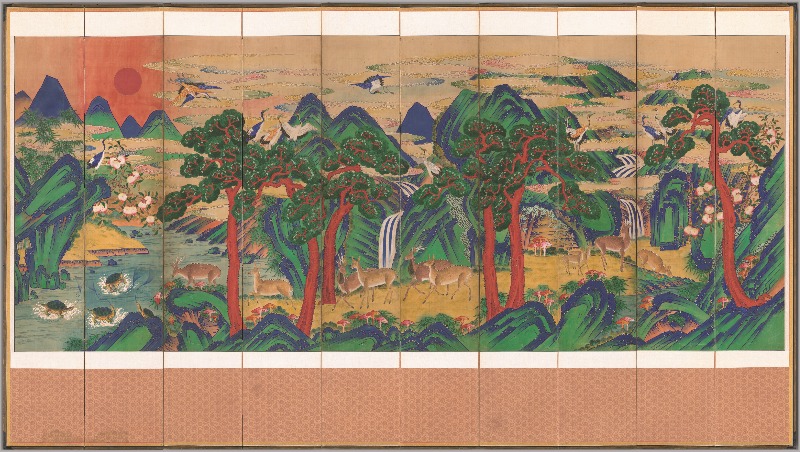

“Ten Longevity Symbols.” Artist unknown. Late 19th century. Ink and pigment on paper. 132.2 × 431.2 cm.

Extant late 19th century paintings of the ten longevity symbols are characterized by flat space composition and conventional depiction of the scenery. This work donated by Lee Kun-hee, the late chairman of Samsung Group, shows a similar trend.

© National Museum of Korea

The ten symbols of longevity come from an old religious and cultural concept in Korea, dating back to the Goryeo Dynasty. Since longevity is a basic human desire, it is symbolized throughout the world. However, it is difficult to pinpoint regions outside of Korea where longevity symbols were chosen, named as such, and then used in paintings. Koreans perceived the sun, moon, mountains, water, stones, pine trees, bamboo, clouds, mushrooms, turtles, cranes, and deer as symbols of longevity. In paintings of the ten longevity symbols (sipjangsaeng), mountains, water, and clouds serve as the background of the immortal world and auspicious animals are depicted enjoying a leisurely life.

On New Year’s Day, the king gave sipjangsaeng paintings to his ministers. That may explain why this style of painting was widely popular not only at the royal court but also among the general population. A large folding screen with these ten symbols was best suited for a celebration of longevity, such as a 60th birthday party.

“Peonies.” Artist unknown. 1820s. Ink and pigment on silk. 144.5 × 569.2 cm.

As the king of flowers and a symbol of wealth, peonies served as an important motif in Joseon ornamental paintings. Many folding screens with peonies remain today, thanks to a large supply that was used frequently for royal ceremonious rites, including weddings, funerals, and ancestral rites.

© National Museum of Korea

Peonies were another fixture of Korean court paintings. In East Asia, the peony is considered the “king of flowers” and symbolizes wealth and glory. Thus, peonies were glorified in numerous literary works and paintings, and planting and cultivating them was a popular pastime.

A large folding screen with colorful peonies supplied the backdrop at weddings and banquets, but it was also used for memorial ceremonies such as funerals and ancestral rites. The peony supposedly embodied an auspicious spirit descended from the sky and hence contained wishes of remembrance. This is why some peonies were painted with petals of four different colors blooming on a single stem. The artist’s goal was to express the spirit manifested in the peony rather than the flower itself.

Various Formats

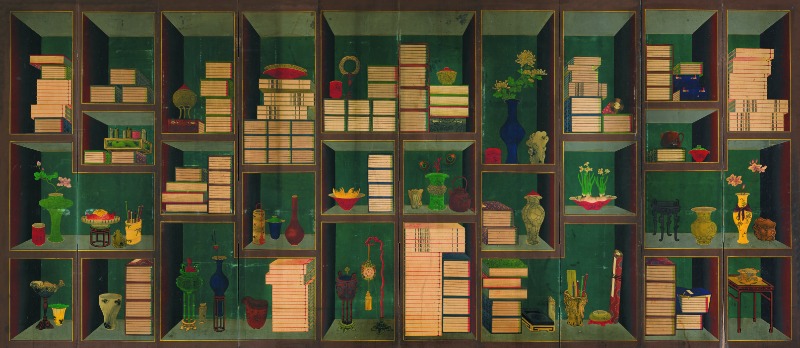

“Chaekgado.” Lee Eung-rok. 19th century. Ink and pigment on silk. 152.4 × 351.8 cm.

This painting of a scholar’s accoutrements on a bookshelf is in a style unique among Joseon court ornamental paintings with its rare display of Western painting techniques.

© National Museum of Korea

Chaekgado paintings, which depicted scholars’ accoutrements on a bookshelf, was introduced from China in the late 18th century. This is a rare example of a type of decorative court painting in which Western techniques were applied. Court artists attempted to use a Western single-point perspective and shading tothe illusion that s in the painting actually existed, as in trompe-l’oeil paintings. King Jeongjo (r. 1776–1800), who emphasized the rule of letters and the law, tried to use this painting style to strengthen the royal authority and edify the people. When he met with his ministers in Seongjeongjeon at Changdeok Palace, a folding screen featuring chaekgado instead of sipjangsaeng loomed behind the throne as the king expressed his thoughts on his studies. He said that when he did not have the time to read books, he found comfort in simply having this type of painting close by.

Yi Eung-rok, the son of an acclaimed painter of the 19th century, was particularly accomplished in chaekgado paintings, and his son and grandson continued his legacy. Court painters usually did not leave signatures on their works, but Yi put his name on a seal in his. In chaekgado paintings, the bookshelf appears real, thanks to the three-dimensional s and the oblique lines of the shelves converging toward the vanishing point in the center. The background color, with low brightness and saturation suited for illusionary paintings, reflects the adoption of Western painting techniques. As such, chaekgado paintings of the 18th and 19th centuries reflect Joseon people’s curiosity about the West.

Some court paintings are not in the form of folding screens or hanging scrolls. One notable example is a hwajodo painting — a style that featured various birds and flowers — found in Gyotaejeon, the queen’s living quarters at Gyeongbok Palace. This painting, spanning more than 2.6 meters, was originally placed above the main hall of Gyotaejeon. The fantastic atmosphere is overwhelming, with flowers and birds descending in an oblique composition. Roses and plum blossoms, symbolizing eternal youth and loyalty, as well as a pair of parrots were painted in the queen’s chamber to express wishes for a happy marriage.

Gyotaejeon was destroyed and rebuilt several times. This painting was presumably attached to the wall when the building was restored in 1888. At that time, it was occupied by Empress Myeongseong (1851–1895), consort of King Gojong (r. 1863-1907). As if the painting’s message was in vain, the empress was assassinated and Gyotaejeon demolished once again. If the Joseon court paintings were witnesses, they would narrate a history of both grandeur and turbulence.

Lee Jae-ho Jeju National Museum Curator