Byoung Soo Cho’s architecture, which explores themes such as “contemporary vernacular” and “organic vs. abstract,” has been described as “refinement in roughness, casualness within refinement.” Cho is renowned for his ability to achieve a balance between the two extremes of Korean naturalness and modernist abstraction. His work expresses his attitude toward Korean culture and philosophy as well as the essence of architecture that he has long explored.

Instead of building his famous Earth House above ground, architect Byoung Soo Cho boldly designed the house such that it is being embraced by the ground itself.

© Kim Jae-kyeong

Concrete Box House is an important example of the architect’s work. A large opening was d in the building’s center to connect the interior space with the outside.

© Hwang Woo-seob

To Byoung Soo Cho, the earth is an architectural theme, and the architect uses the existing topography as much as possible to minimize damage to it. He also concentrates on expressing the experience of humans communicating with nature through the medium of architecture.

© texture on texture

Modern Architecture: A Critical History, Kenneth Frampton’s highly acclaimed survey of modern architecture and its origins, has been a classic since it first appeared in 1980. But it wasn’t until a new chapter appeared in the fifth edition, published in 2020, that the British-American architect and historian mentioned Korean architecture. In his description of Korea’s relatively late entry into the modern architectural scene, the author highlighted the works of notable Korean architects Kim Swoo-geun (1931–1986), Byoung Soo Cho (*1957), and Minsuk Cho (*1966). This inclusion in Frampton’s seminal work introduced Byoung Soo Cho, head of his namesake BCHO Architects studio in Seoul, to a global audience.

Cho decided to study architecture in 1978, after seeing an architectural drawing for the first time at an exhibition that commemorated the completion of the Sejong Center for the Performing Arts at Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Square. Thinking that he might benefit from studying in the home country of writer Mark Twain, he left for the U.S.

“I had come across Mark Twain’s What Is Man? at a used bookstore near Cheonggye Stream in Seoul. I was shocked by Twain’s dark portrayal of human nature, which led me to ponder the same question.” Ever since reading the short story, Cho’s faith in humanity has remained at the center of both his life and his work as an architect. It also led him to explore emotional architecture, as he began asking himself questions about emotion and reason.

Experiential Architecture

Cho found his new life on the pastoral campus of the University of Montana somewhat simple. One day, he looked up at the sky and saw the beauty of nature, although the scenery was relatively unremarkable. He was particularly inspired by the barns of Montana, whose unadorned yet practical structures he found to be similar in some ways to traditional Korean architecture. After enrolling in the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Cho began a thorough exploration of his chosen theme of “experience and perception.” At that time, there was a growing sense of skepticism and reflection on modern architecture in the Western world.

“I was deeply moved by Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science by Prof. Alberto Pérez-Gómez of McGill University, and also by Kenneth Frampton’s article ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance.’ I felt that the reflection on modern architecture should start from the perspective of humans communicating with nature. I also felt that Korean architecture offered that alternative.”

Cho focused on the way in which Korean architecture blends easily and organically with nature, thanks to its lack of complex detail or exaggeration. This served as the motivation for his pursuit of “experiential architecture” beyond visual proportions or forms, which he made the subject of his master’s thesis. In his work, Cho focuses on people’s experiences of spaces, how those experiences influence their perception of nature, and the relationship between structures and empty spaces.

Box Series

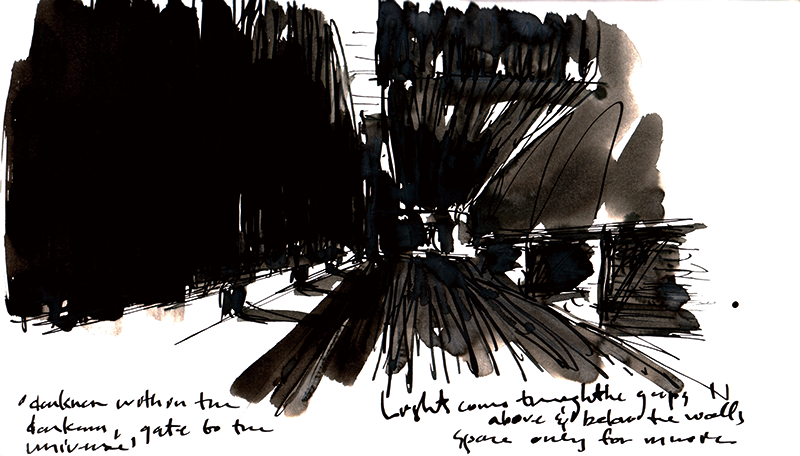

Architectural sketch for Camerata Music Studio, Gallery & Residence, a combination of music studio and living space.

Courtesy of Byoung Soo Cho

The first floor of the three-story Camerata building is used as a music studio. To convey the look of a barn in Montana, the interior columns were eliminated, and the long concrete wall to the west was given a rough texture. The ceiling shown in the photo doubles as the wire-suspended floor of the mezzanine on the second floor. The rough texture of the concrete enhances sound absorption, with the help of a grooved wooden panel.

© Kim Jong-oh

After completing his studies, Cho returned to Korea and embarked on his architectural career. Plywood with a stainless steel finish, Galvalume roofing, and slender columns, which he used for the Village of Dancing Fish, a special needs housing project in Paju, Gyeonggi Province, were the best choice given the limited budget. Cho’s combination of simple details and materials d an interesting composition. As he explained, eco-friendly buildings are often the result of exploring cost-effective solutions.

Two more of Cho’s early works are today considered iconic examples of his architectural world. Sitting on a peaceful hill in Yangpyeong, Gyeonggi Province, the Concrete Box House, shaped like the Korean letter ㅁ, serves as the architect’s second home and embodies the concept proposed in his master’s thesis. The square courtyard with its ten columns made of reclaimed wood is reminiscent of the gardens in traditional Korean houses, or hanok. However, rather than mirroring traditional architectural forms, Cho’s design seeks to invite light, air, and the elements into the building and provide a view of the sky.

The building’s structural experimentation is particularly noteworthy. Tothe simple concrete box, Cho used a natural method of waterproofing the concrete during the curing process, thus avoiding the use of chemical agents. His use of concrete and wood, two materials with contrasting contraction rates, was a risky but ultimately successful experiment. The interior is supported without beams, relying only on the wooden columns spaced five to six meters apart, which allows for an even distribution of force. This also enabled the use of a square, flat roof without parapets. Crucial to the entire project was Cho’s intimate knowledge of concrete slump and the dimensional shrinkage of wood.

Located in the Heyri Art Valley in Paju, the Camerata Music Studio, Gallery & Residence is both a recording studio and the home of renowned disc jockey Hwang In-yong. Cho sought to maximize the studio’s sonic experience, drawing inspiration from barns in rural Montana. The bold idea of filling a dark space with music and a single beam of light resonated with Hwang’s childhood memories of a salt storage barn. To enhance the auditory experience, Cho removed the interior columns and suspended the mezzanine with wires. The acoustic challenge was met by roughening up the concrete ceiling to act as an absorbent panel, a smart solution given the project’s budgetary constraints. In addition, a courtyard was d between the building’s two box-like sections, one housing the music studio and the other serving as Hwang’s private residence.

Cho went on to continue his box series, combining simple forms toin-between spaces and revealing experiences beyond architecture. Later on, the architect’s work evolved and became more dynamic as he bended and twisted the straight lines of his earlier designs and began to use naturally flowing curves.

Reflection on Earth

With a total area of six pyeong (roughly 20 square meters), Earth House comprises two bedrooms, as well as a library, kitchen, bathroom, and boiler room, each with an area of one pyeong (3.3 square meters). Along with the two doors leading to the courtyard, the main entrance to the house is so small that visitors have to duck when they enter. The architect intended this as a way of expressing moderation, self-reflection, and humility.

© Kim Yong-kwan

Cho’s experiments led him to design his Earth House. Boldly dug into the ground, the building’s concept originated from his familiarity with earth, but it also reflected his belief that the simpler the space, the easier it is to experience the sky, trees, stars, and wind. This belief was also present in Cho’s Jipyoung Guesthouse, named after its guiding concept, which translates to “horizon.” Most of the building is subsumed into the side of a cliff such that it commands a natural view of the ocean, with the space embraced by the earth around it.

Cho further developed this interest in earth and land at the 4th edition of the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism in 2023, where he served as general director. How can we restore the paths of the mountains, water, and wind of Hanyang (the name of Seoul during the Joseon period)? Cho asked himself this question with the aim of connecting the original terrain of Seoul, which is surrounded by mountains, with its waterways, creating pleasant, pedestrian-friendly spaces with a refreshing breeze.

Recently published by Thames & Hudson, Cho’s book Byoung Cho: My Life as an Architect in Seoul discusses the natural environment of the city where he was born and raised, and the range of architectural works he has d that express his thoughts on nature and the South Korean capital. For Cho, earth is not an abstract concept found in the study of the humanities, but rather a physical reality that directly influences how we experience space. “I believe in the importance of the natural environment, the cultural environment, and their respective contexts. I am especially interested in their physical contexts, including topography, wind, and water.”

A look at Cho’s home and office as well as the buildings he has designed offers a glimpse into the original form of spaces that have been lost due to the rapid urbanization of Korea. At an age where others enjoy their retirement, the architect maintains a routine of taking walks in the morning, working happily during the day, and socializing with friends over wine in the evening. He is mindful of the Dalai Lama’s teachings on relationships, as he strives to practice emotional architecture. For an architect with a career that now spans some 30 years, architecture is all about creating a warm space for living as well as a form of intellectual stimulation.

Concrete Box House includes ten wooden columns set five meters apart, all connected to a 20-centimeter-thick concrete roof. The combination of wood and concrete, materials with different contraction rates, was one of the architect’s experiments, which proved to be a success.

© texture on texture

Jipyoung Guesthouse was built following the complex contours of the earth as if it were permeating into the building. Indigenous plants are seen growing out of the cracks in the concrete walls and on the roof; this was the architect’s way of allowing the architecture to harmonize with its natural surroundings.

© Sergio Pirrone

Lim Jin-young CEO, OPENHOUSE SEOUL