In recent years, Korean art museums dedicated to a particular artist have been established by local governments or cultural foundations to commemorate their individual legacies. They pay tribute to artists who have left an indelible mark on Korean art history, treasuring their artistic achievements and perpetuating their names.

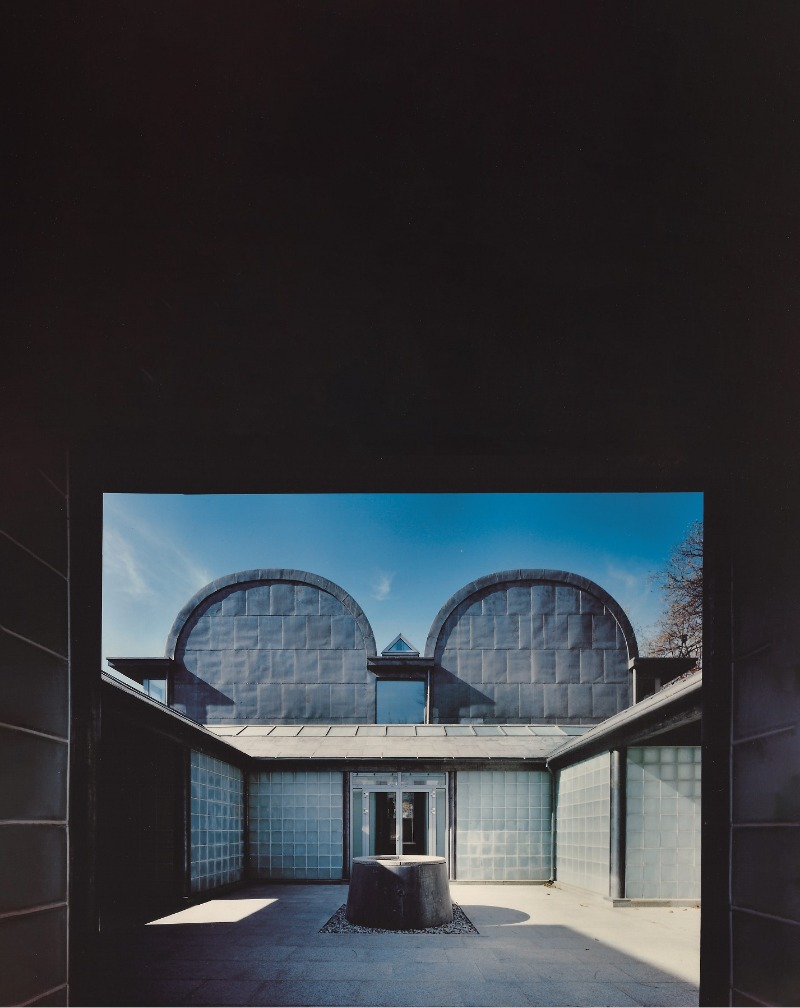

The main entrance of the Whanki Museum at the foot of Mt. Bugak in Seoul. Comprising softcurves, the lower part of the main building is made of stone, while the semicircular roof is finished with lead-coated copper plates. Opened in 1992 to commemorate the artist and his oeuvre and support contemporary artists, the museum won the Kim Swoo-geun Architecture Award in 1994.

ⓒ Whanki Foundation•Whanki Museum

Art museums named after an individual fall largely into two categories. The first are those named after a patron who was an avid art collector, such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum or the Whitney Museum of American Art. These museums provide an interesting window into their patrons’ collecting philosophy and the place of their works in the flow of art history. The second are museums dedicated to a single artist, such as the Van Gogh Museum, Musée Picasso and Musée Matisse, which offer a multifaceted view into the respective artists’ lives and works.

Over the past ten years, Korea has seen a marked increase in such single-artist museums. They are usually built in the artists’ hometowns or places otherwise connected to them in some way. The Jong no Park Nosoo Art Museum in Jongno District and the Choi Man Lin Museum in Seongbuk District, Seoul, are examples of artists’ residences turned into public art galleries that have become popular attractions. Park No-soo (1927-2013), who majored in Korean painting, is known for his clean, contemplative style, and Choi Man Lin (1935-2020) was one of the pioneers of abstract sculpture in Korea.

The Kim Chong Yung Museum in Pyeongchang-dong and the Kimsechoong Museum in Hyochang-dong, Seoul, are art galleries highlighting marginalized sculptors. Quaintly elegant, the museums themselves are beautiful works of art. While Kim Chong Yung (1915-1982) was a pioneering Korean abstract sculptor whose works radiated vitality, rooted in his keen insight into people and nature, Kim Sechoong (1928-1986) was largely immersed in religious themes. Such museums dedicated to single artists host special exhibitions and educational programs illuminating the artists’ lives and oeuvres and giving visitors the chance to learn more about them.

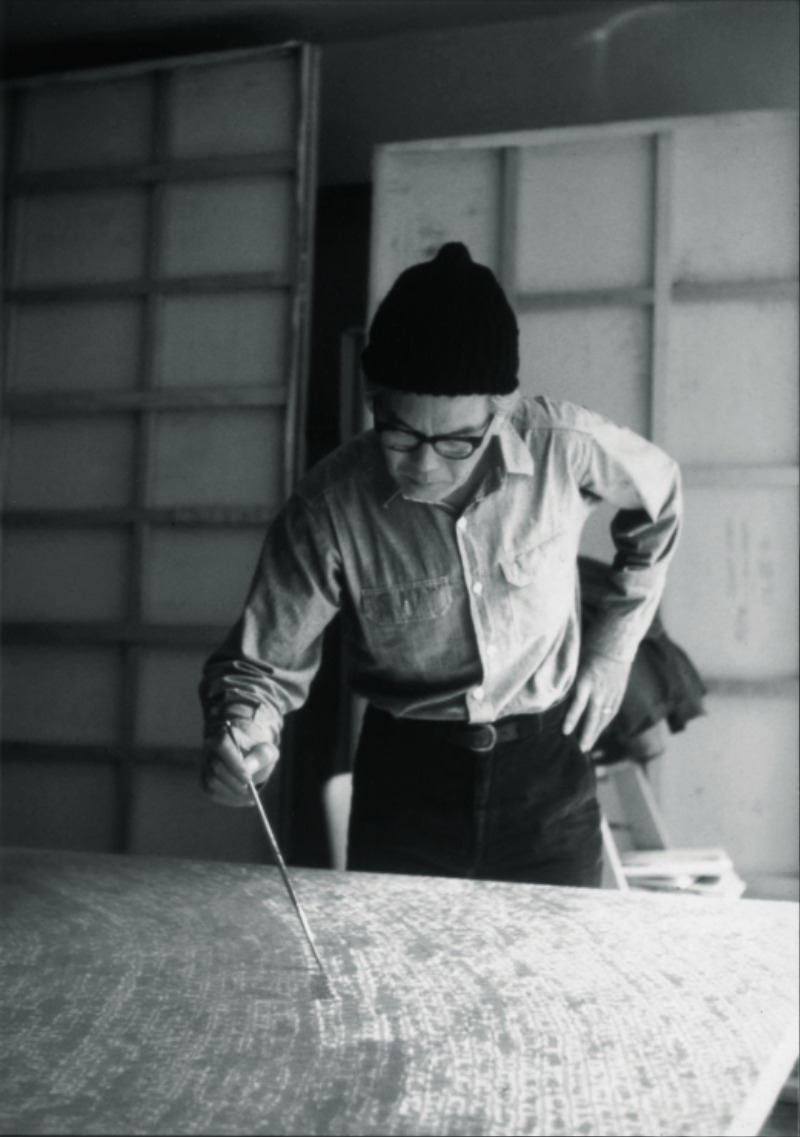

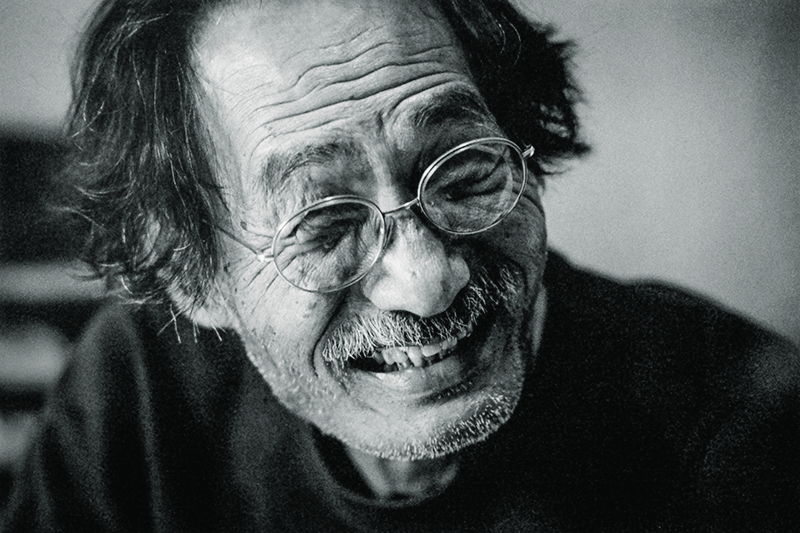

Kim Whanki developed a distinctive style incorporating Western modernism with lyricism that expressed Korean sentiments.

ⓒ Whanki Foundation•Whanki Museum

Two Hearts, One Mind: The Whanki Museum

Kim Whanki (1913-1974) is undoubtedly the most prominent artist in Korean art history. This honor is well deserved not just because one of his most recognized works, “Universe 05-IV-71#200” (1971), sold for HK$88 million (around US$11.2 million) at a Christie’s auction in Hong Kong in 2019, setting the record for a Korean artist. When studying in Japan, Kim learned Western painting techniques and used them to express very Korean sentiments, using motifs such as the moon, mountains, the ocean, white porcelain vessels, cranes and plum blossoms.

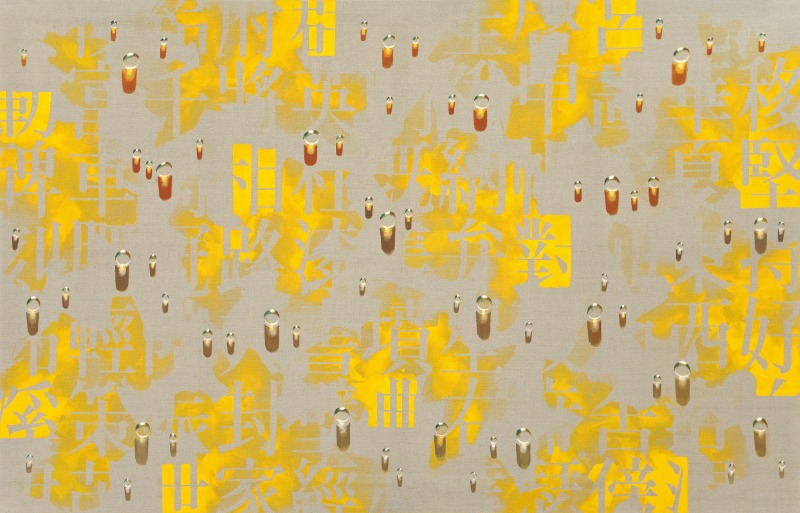

Although a bright future lay ahead of him in Korea, Kim left behind fame and stability and went to New York in 1963. There, he encountered abstract ism, based on which he d a uniquely Korean abstract art that embraced subtle lyricism. This proved that he was capable of rising above himself and the person he was in the past, another reason why he remains revered to this day. In his abstract dot paintings, Kim painted thousands of dots that filled the entire canvas, no single bleeding or overlapping dot looking the same.

Located in hilly Buam-dong, Seoul, the Whanki Museum can be reached by climbing a winding alleyway. Set against Mt. Bugak, the museum itself is like a beautiful painting. After Kim’s passing in 1974, his wife Kim Hyangan (1916-2004), a writer, donated many of his artworks, which made possible the museum’s opening in 1992. It houses the largest number of Kim Whanki’s dot paintings, worth millions of dollars.

The exhibition hall showcasing Kim Whanki’s dot paintings from the 1970s.

ⓒ Whanki Foundation•Whanki Museum

Kim Hyangan’s real name was Byeon Dong-rim. She was a modern woman who first married Yi Sang (1910-1937), a poet and writer who was a pioneer of modern Korean literature. But lung disease took Yi’s life at a young age, just several months into their marriage. Seven years later, Byeon was introduced to Kim Whanki, a lanky widower with three children. Despite her family’s adamant ions, she married Kim and took his pen name “Hyangan” as her new name. Sensing that her husband needed a change of scenery, she proposed moving to Paris. She left ahead of him to look for a studio, and he joined her a year later. After Kim passed away in New York, she established a foundation in his name and opened an art museum in Buam-dong, close to the city center but surrounded by nature. Staying true to her promise, she spent the rest of her life upholding her husband’s name.

A unique feature of the Whanki Museum are the two semicircular barrel-vault roofs, attached side by side so that the main building resembles two people standing next to each other. Kim’s later works, such as “Duet 22-IV-74 #331” (1974), feature abstract images of two people standing together, rendered in dots and lines. The two tall pine trees in the museum’s courtyard also bear a resemblance to the artist and his wife.

Longing for Family: The Chang Ucchin Museum of Art in Yangju City

Chang Ucchin (1917-1990) was an artist known for his innocent portrayals of nature and family. In 1963, he set up an atelier in Deokso in Yangju City, Gyeonggi Province, where he could enjoy the beauty of nature not too far from his family in Seoul. His 12-year stay there was an active time, during which he held his first solo exhibition and participated in group exhibits. It was a period in his career when he sought experimentation and innovation.

In 2014, the Chang Ucchin Museum of Art in Yangju City was inaugurated with 260 artworks his family donated to the city. The murals “Table” (1963) and “Animal Family” (1964), removed from the walls of his atelier in Deokso when it was torn down, are part of the museum’s permanent exhibition. The simple white design of the museum building echoes the simplicity of Chang’s painting style. It was designed by architects Songhee Chae and Laurent Pereira of Chae Pereira Architects and based on a motif from the artist’s painting “Tiger and Magpie” (1984).

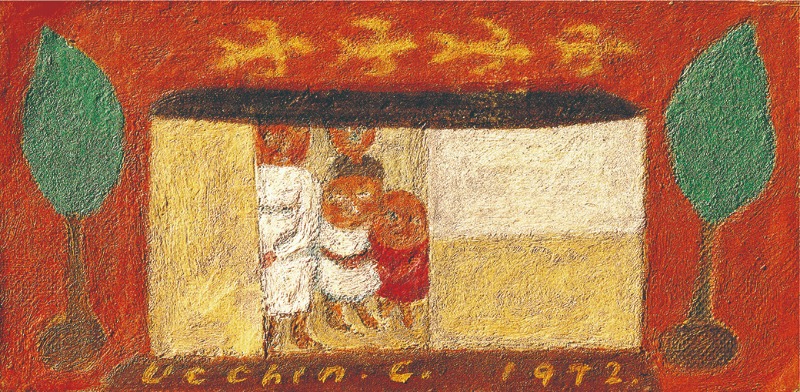

Chang liked small paintings. In the donated collection, the most noted work is “A Family Portrait” (1972), the size of an adult’s palm. The small house in the painting fills the entire canvas. It has just enough space for four people: a family consisting of a mustached artist father, a mother dressed in white, and two children with hands neatly gathered in front. The house is set against a red background, possibly depicting the sunset the family is admiring. The trees flanking the house look like guardians protecting them.

In front of the museum is a valley. In the summer, many family visitors come not only for the exhibitions but also to play in the water, and in spring and autumn, to enjoy the beautiful spring blossoms and fall foliage. Chang disliked the bustling city and would have loved his namesake museum where he could revel in the ever-changing seasonal landscape. It seems to embody his artistic style, characterized by bold surrealistic composition and harmony of nature, animals and humans.

The Chang Ucchin Museum of Art in Yangju City opened in 2014 to honor one of Korea’s most prominent modern and contemporary artists. In October that year, it was selected as one of the eight greatest new museums in the world by the BBC.

ⓒ Chang Ucchin Museum of Art, Yangju City

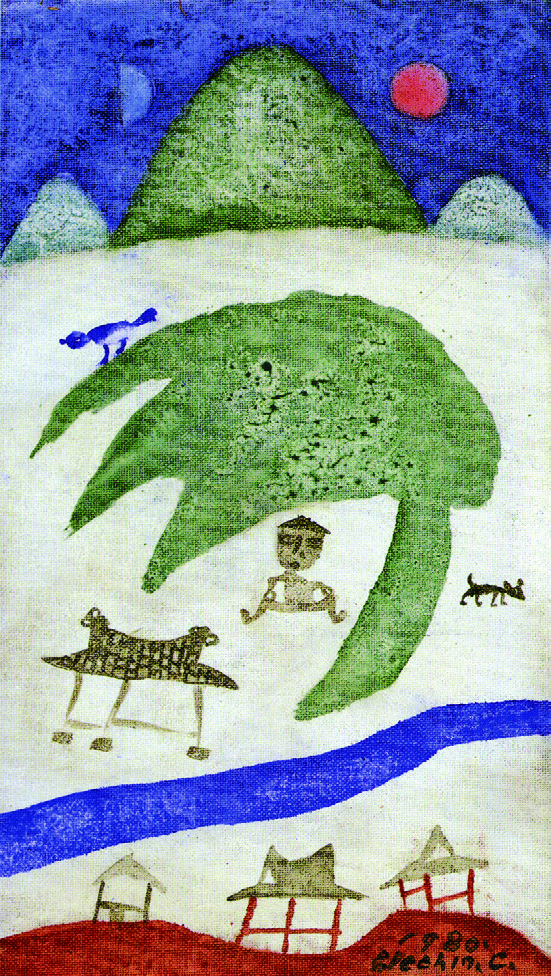

“Child.” 1980. Oil on canvas. 33.4 × 19.2 cm.

One of Chang’s paintings from the early to mid-1980s, when the artist lived in Suanbo. His works from this period are suggestive of landscape paintings.

ⓒ CHANGUCCHIN FOUNDATION

“A Family Portrait.” 1972. Oil on canvas. 7.5 x 14.8 cm.

A painting from Chang’s later years in Deokso, showing the symmetrical composition characteristic of his works.

ⓒ CHANGUCCHIN FOUNDATION

Chang chose subjects from everyday life, such as houses, trees, children and birds, expressing their fundamental nature in a bold, simple style.

ⓒ Kang Woon-gu

Paintings Come Home: The Park Soo Keun Museum in Yanggu County

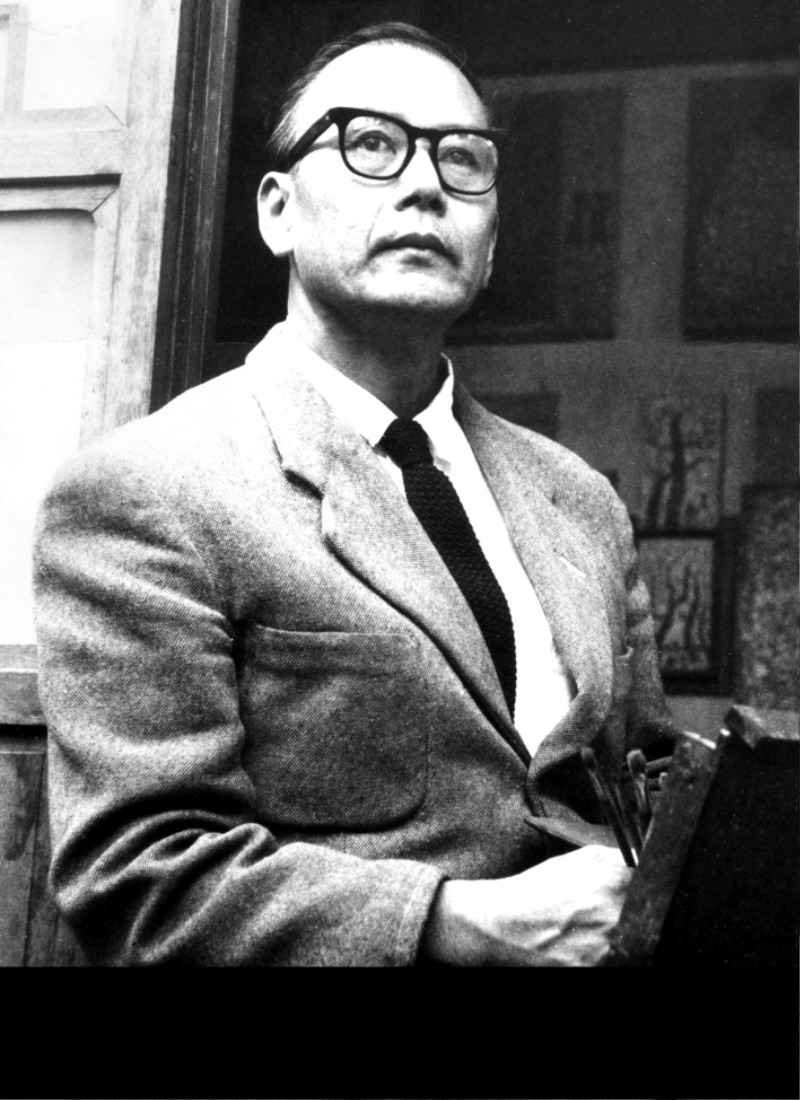

Park Soo-keun, who liked to capture images of ordinary people on canvas, achieved a folksy aesthetic with simplified lines and composition on rough textures that look like granite.

ⓒ Moon Sun-ho

Park Soo-keun (1914-1965), one of Korea’s most beloved artists, was born in Yanggu County, Gangwon Province. After seeing a picture of Jean-François Millet’s “L’Angélus” at the age of 12, he resolved to become a painter. Abject poverty prevented him from obtaining a formal art education, let alone going abroad to study, so he taught himself how to paint. Nature was his teacher; his senses were his guide.

After the Korean War, Park worked at a U.S. army PX (post exchange), drawing portraits. Park Wansuh (1931-2011), one of the most prominent writers in Korea who is known for her profound portrayals of Korean society, including its dark underbelly of capitalism and the anachronistic family system, was working at the commissary at the time; it is commonly known that Park Sookeun inspired her to write her debut novel “The Naked Tree.”

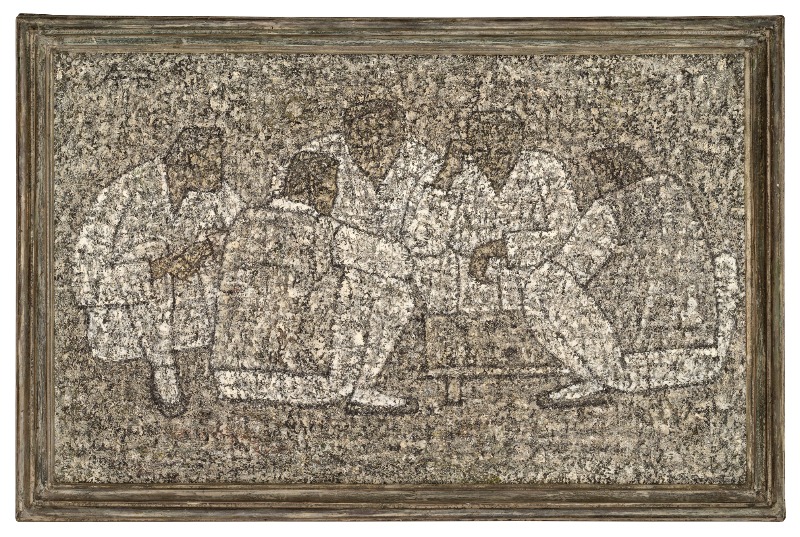

Park had a predilection for painting leaf less trees, their bare branches hiding flower buds and shoots waiting to bloom in spring. His modest and desolate paintings whisper of hope and longing. He employed a distinctive matière technique of painting, drying and repainting multiple s, thereby creating a unique texture that makes the finished painting look like a rock carving. The figures in his works are expressed in simple lines with indistinct facial features. It is difficult to identify them or discern their facial s; they seem to be universal figures representing their time. The mothers in his works can be seen as one’s own mother or everybody’s mother. Their simplified forms have the sublimity of religious paintings.

The Park Soo Keun Museum in Yanggu County opened in 2002 at the site of the artist’s birthplace. Architect Lee Jong-ho designed the museum to look as if it were engraved in the ground like one of the artist’s paintings. Nestled in nature, the museum has a cozy, peaceful atmosphere. It currently houses over 235 works, including pieces donated by the artist’s family and patrons as well as acquisitions the museum has been making every year. Lee Kun-hee (1942-2020), the late chairman of the Samsung Group who was an avid art collector, was also a huge fan of Park’s works. Lee purchased “Leisurely Day” (1950s), which had been owned by a private collector, at a Christie’s New York auction in 2003. His family donated the piece to the museum in 2021, along with three other oil paintings and fourteen sketches. Park’s warm, earthy paintings depicting hometown sentiment had finally come home.

The Park Soo-keun Pavilion, located on the grounds of the Park Soo Keun Museum in Yanggu County. Built in 2014 to commemorate the centennial of the artist’s birth, it displays works donated by patrons.

ⓒ Park Soo Keun Museum in Yanggu County

The Park Soo Keun Museum in Yanggu County was built at the site of the artist’s birthplace in 2002. Piles of irregularly shaped granite are ed up, resembling the rough texture of Park’s paintings. The museum began with only a small collection as his works were so highly priced in the market, but it has since gathered 235 pieces through donations and acquisitions.

ⓒ Korea Tourism Organization

“Leisurely Day.” 1959. Oil on canvas. 33 x 53 cm.

Park submitted the painting to the 8th National Art Exhibition of the Republic of Korea held in 1959. Lee Kun-hee, the late chairman of the Samsung Group, purchased it in 2003 at a Christie’s New York auction, and his family donated it to the museum in 2021.

ⓒ Park Soo Keun Research Institute

“Tree and Two Women.” 1956. Oil on hardboard. 27 x 19.5 cm.

One of Park’s most famous works, this painting features a bare tree symbolizing the Korean people after the Korean War, who never lost hope. It is presumed to be the motif of Park Wansuh’s debut novel “The Naked Tree” (1970).

ⓒ Park Soo Keun Research Institute

Return to His Roots: The Kim Tschang-Yeul Art Museum on Jeju Island

The Kim Tschang-Yeul Art Museum in Hallim-eup on Jeju Island houses the artist’s first waterdrop painting. Widely known as the “waterdrop painter,” Kim Tschang-yeul (1929-2021) was born in Maengsan, South Pyongan Province, in present-day North Korea. He was a bright child, not only talented in art but mastering, at a young age, the “Thousand-Character Classic.”

Branded an anti-communist when he was 17, Kim fled North Korea to the South, making the trip alone across the 38th parallel dividing the two countries. After spending six months at a refugee camp, he was miraculously reunited with his father. Happy to see his son alive, Kim’s father relented and permitted his son to pursue his dream of painting, and so Kim entered Seoul National University’s College of Fine Arts. After the Korean War broke out, Kim joined the police force instead of the military. After graduating from the police academy, he worked on Jeju Island for around a year and a half. His history with the island is what led to the opening of his namesake museum there.

The Kim Tschang-Yeul Art Museum on Jeju Island was established in 2016 to commemorate the artist’s achievements and spirit. The museum, which takes its design motif from Kim’s waterdrop paintings, hosts special exhibitions on various themes and educational programs.

ⓒ Kim Tschang-Yeul Art Museum•Jeju

Kim’s works from the 1960s are dark and sticky. They can be classified as Art Informel, expressing post-war existentialism with formless passion. The clumps of paint, like the lump in a person’s heart, gradually change into a sticky liquid oozing out of a hole. They appear like tears of blood silently shed by those suffering from the scars of war. As invitations to overseas exhibitions increased, Kim moved to New York, then relocated to Paris in 1969. It was a time of financial hardship. His workroom was an old stable, and unable to afford materials, he reused canvases after splashing water on them and removing the paint. One morning, he saw a bead of water dangling on the canvas glistening in the light and had a eureka moment.

Kim’s drops of water painted on hemp are hyper-realistic, as though they would glide down if the painting was shaken. It is actually an optical illusion d by the juxtaposition of the colors white and yellow, and the undrawn areas and shaded parts. The luminous droplets, looking like voluminous empty orbs, are a paradox expressing the delicate tension between bouncy tautness and flowing gravity. Deceptively simple, these paintings have garnered Both critical and popular acclaim.

The museum building is in the shape of a small square inside a large one, like the Chinese character “hoe” (回), meaning “to turn.” At 60, Kim embarked on his “Recurrence” series, featuring waterdrops over characters in the “Thousand-Character Classic.” It signified a return to his roots, the first time he held a brush. “I was born in Maengsan and managed to come to Jeju Island without being eaten alive by tigers,” Kim said at the museum’s opening in September 2016. “My wish is to spend my last days here, that is, if I’m not eaten alive by sharks.” In accordance with his last wishes, he was buried under a tree beside the museum. Although Kim never returned to his hometown in the North, he was laid to rest on Jeju Island, his second home. The artist lives on through his artworks and the museum bearing his name.

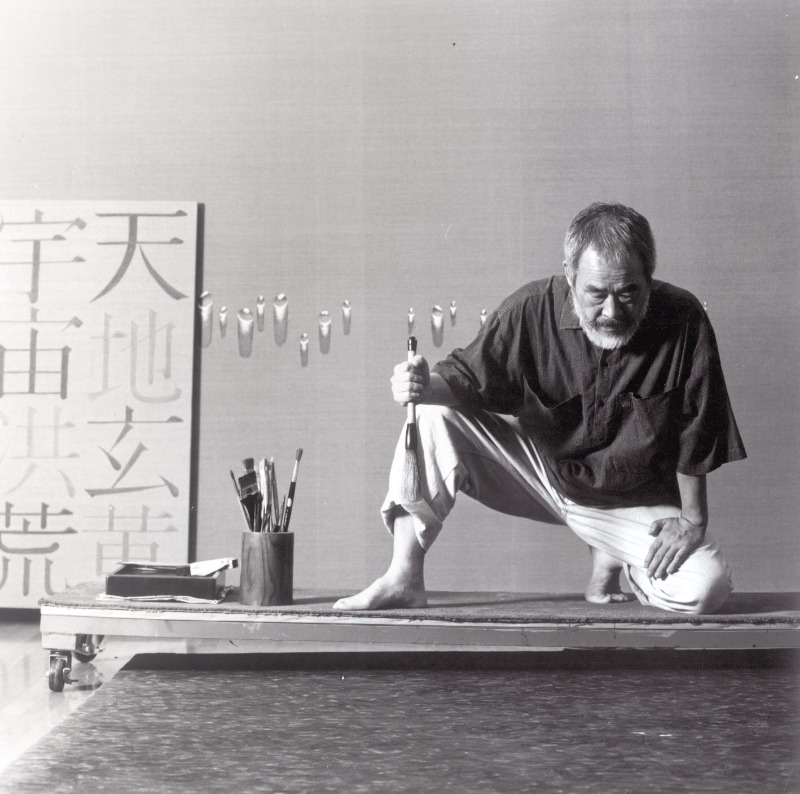

Kim participated in the Art Informel movement of the 1960s; in the early years, he focused on abstraction, expressing suffering from the scars of war. After unveiling his first waterdrop painting at an exhibition in Paris in 1972, he continued to explore the form of droplets using diverse materials such as newspapers, hemp, sand and wooden boards.

ⓒ Kim Tschang-Yeul Art Museum•Jeju

“Recurrence.” 2012. Acrylic on hemp. 195 x 300 cm. In the mid-1980s, Kim embarked on his “Recurrence” series, featuring waterdrops over characters from the “Thousand-Character Classic.” They represent Eastern philosophy and spirituality.

ⓒ Kim Simon