Kim Dong-sik is a master in the art of fan making. For over 60 years, he has made traditional fans in Jeonju, North Jeolla Province, running a family business that has continued over four generations.

Back when the luxury of air conditioning and electrical fans was nonexistent, hand fans were a summertime necessity. People used them to stir the air to cool themselves, and also carried them as an accessory to show their social status or as a ceremonial item at weddings and funerals. Joseon Dynasty yangban were particularly fond of folding fans, especially those with double-ed bamboo ribs (hapjukseon). Unfolding their fan with a flourish, they would cool themselves, snap it closed again, then put it back into the wide sleeve of their robes that served as a pocket. Some treasured the painting on the fan’s leaf as if it were a work of art, while others used it to scratch their itchy back or as a weapon in an emergency. Fans were also useful for secret lovers who wanted to hide their faces.

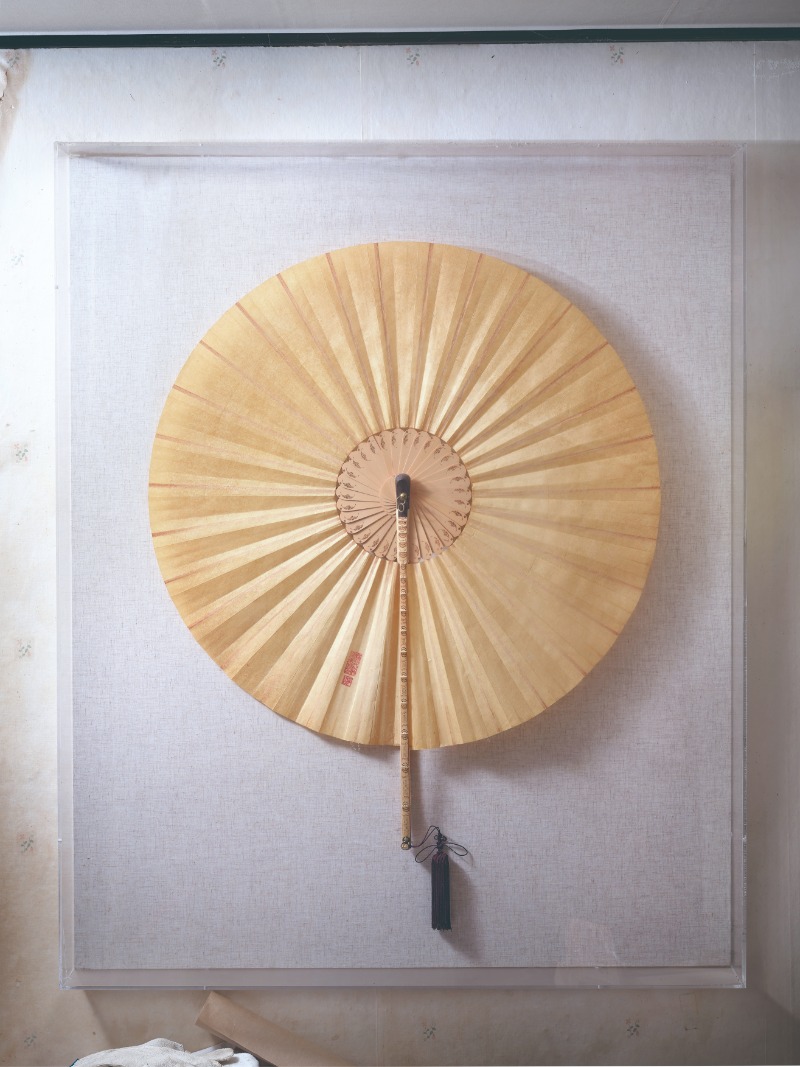

Traditional Korean fans are divided into two major types: rigid round fans (danseon) and folding fans (jeopseon). The rigid fans have ribs radiating from the handle, while the folding fans are further classified into various types according to the number and material of the ribs, the way the leaves are decorated and the parts and accessories used. Among them, the hapjukseon, decorated with mother-of-pearl inlay, metalwork, lacquer work or jade work, is an exquisite type of folding fan that was an important diplomatic gift item when it was developed in the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392).

During the Joseon Dynasty, the number of ribs on fans was specified according to the user’s social standing: 50 for the royal family, 40 for the upper classes and fewer than 40 for the upper middle class and ordinary people. “A Record of Seasonal Customs in Korea” (Dongguk sesigi), written by the late Joseon scholar Hong Seok-mo (1781-1857), states that the fans offered to the king on Dano Day in the spring were distributed to his courtiers and attendants. The state operated Seonjacheong, an agency responsible for making fans, and the Jeolla Provincial Office supervised the production and collection of fans to be sent to the king.

Painstaking Process

In his workshop filled with bamboo stalks, the artisan Kim Dong-sik holds up a thin bamboo strip. “To make a hapjukseon, bamboo strips are cut this thin from the outer part of the culm, and two strips are glued together, the skin facing outward, to make one rib of the fan. Compared with Chinese and Japanese folding fans made with the softer inner parts of bamboo, hapjukseon last much longer. Durability is one of the defining characteristics of traditional Korean folding fans,” he says.

Kim completes 140-150 procedures to make a single fan. The first step is obtaining the most suitable bamboo culms. A bamboo tree grows to its full height in the first year and then ripens only on the inside, taking at least three years to obtain the proper hardness.

“Young bamboo may look better, but it’s too soft inside when split. Three-year-old trees are the best. The yearly stock of bamboo should be acquired in the dry weather of December and January since the wood gets moth-eaten when it’s humid,” Kim explains.

Spotless bamboo culms are split into the size of the fan ribs, and the sticks are soaked in water for five days so the greenish skin turns yellow. The sticks are softened in boiling water and cut away at the inner side until they’re 0.3-0.4 mm thick. By this time, almost two thirds of the original stick have been removed.

The next part is the hardest: the strips should be cut so thin that light can pass through them. “That way, the fan opens and closes smoothly and the flexible frame can stir a cool breeze with the slightest movement of the hand. The outer surface of the bamboo culm is so hard and resistant to decay that a folding fan can last for over 500 years if it’s properly looked after,” says Kim.

The thin strips are glued together to make the ribs, which are arranged in a fan shape and then dried for about a week. For durability, two kinds of glue are used in a 4:6 mixture. The first is made from dried and boiled air bladders of croakers, and the second from animal bones, tendons and leather simmered together for a long time. Once the skeleton of the fan is completed, the lower parts of the ribs are decorated with bats, cherry blossoms, dragons and other designs using heated iron tools.

The next procedure is to cut and polish the materials used for the outer guards, preferably wood from jujube trees, birch trees or the heartwood of old, blackened persimmon trees. The guard sticks are decorated with thin bamboo plates or coated with black or red lacquer and brilliant mother-of-pearl inlays. The skeleton is then polished smoothly, the ribs evenly glued, and the leaf cut from hanji (mulberry paper) is attached. Finally, a pivot ring made of brass, nickel or silver is inserted in the head to fix the guard sticks and complete the fan.

Up until the 1920s, the production process was divided into six parts, each one handled by a different artisan. This was possible when the demand for hand fans was still high.

Cutting bamboo culms into thin strips is the most difficult part of making hapjukseon, says master fan maker Kim Dong-sik, who runs a family business that has continued over four generations.

Oldest Fan-Making Business

Once the double-ed strips are prepared, the remaining work is done in a separate workshop. Except for mealtimes, this is where Kim spends all his working hours. The cast iron knives and tools hanging in neat rows on one wall and the ancient-looking workbench attest to the experience and expertise of this master craftsman who has dedicated over 60 years of his life to making fans the traditional way.

Gesturing toward the knives, Kim says, “At first, the knives had wide blades, but 20 years of repeated use and sharpening has worn them down to look like narrow fillet knives. This file was made and used by my maternal grandfather before I inherited it.”

A black-and-white photograph of his grandfather hangs on the wall between the shelf and the door. He was a skilled artisan of the late Joseon period whose fans were sent to King Gojong as a tribute. Kim had the good fortune of learning his skills in detail from his grandfather when he was a child.

Kim’s is the oldest fan-making business in Korea. It began with his great-grandfather on his mother’s side and was succeeded by his grandfather in the photograph (Rah Hak-cheon), then his uncle (Rah Tae-sun) and then finally by Kim himself. He was introduced to the craft in 1956, when he was 14 years old. As the eldest child in a poor family with eight children, he was taken out of school and sent to his mother’s parents to learn the craft. A large number of fan-making artisans lived in the village, and bamboo and hanji, the main materials for making fans, were readily available in the area.

As hand fans were a household necessity at the time, a skilled craftsman could make a modest living. “At first, I helped with odd jobs and learned things just by watching. I guess I was good with my hands; I could cut neat bamboo strips with ease,” Kim recalls. “The adults noticed and began to teach me properly. I was so quick and eager to learn that they praised me lavishly, which made me try harder.”

Perhaps the difference between a mere technician and an artisan lies in dedication. Once he had started, Kim made up his mind to “make great works of art.” He wanted to make fans of his own style using the skills his grandfather had passed on. His fans fit snugly in the palm when folded; when they are opened into a semicircle, the ribs are in perfect symmetry.

Nevertheless, financial difficulties occasionally forced Kim to consider giving up. After underwriting a bad loan, he could barely put food on the table, let alone buy materials for fans.

At that time, one of his friends gladly lent him some money along with advice that he would never forget: “You’re a natural-born fan maker, so never give up.” These words were so deeply engraved in Kim’s heart that he has since stuck to his craft at any cost.

Kim Dae-sung, the artisan’s son, became a designated trainee in 2019 and is carrying on his father’s craft to keep the tradition alive.

National Intangible Cultural Heritage

Kim makes every part of his fans with his own hands. His pride in creating an artwork has sustained him to this day, but financial worries have never left him.

“You can’t make a living making fans now, so young people don’t want to learn the craft. I didn’t want to see the tradition die in my generation, so I cautiously asked my son if he would like to learn it, although he had his own job at the time. I was grateful when he said he would try it,” Kim says.

His son, Kim Dae-sung, took up his father’s craft in 2007. He quickly learned the skills that he had seen his father use all his life and became the fifth-generation artisan in the family. His son’s commitment encouraged Kim to seek official recognition for the art of fan making. Applying for the title of cultural heritage holder, he ed related materials and systemized the production process over three years. In 2015, he was designated as the first National Intangible Heritage title holder in the art of fan making. Since then, other fan makers have received the same recognition, and his son became a designated trainee in 2019.

At the end of the interview, a young man who has been cutting bamboo strips at one corner of the workshop finishes his work and joins us. This is Kim’s grandson, the son of Kim Daesung.

“My grandson is a university freshman. He said he wants to try learning how to make fans. I appreciate his interest but I’m not sure if I should encourage or discourage him,” Kim considers.

Lee Gi-sook Freelance Writer

Lee Min-hee Photographer