Violent Korean dramas have grabbed headlines as global hits, but dramas with an alchemy of romance, comedy and character development are the core of Korean video entertainment. The new term “K-melodrama” reflects values that appeal especially to young adults.

“Kingdom,” “Squid Game,” “Hellbound” and “All of Us Are Dead” – a newcomer to Korean television dramas through Netflix’s recent global hits might assume that they’re all about terror and gore.

But stories laced with romance, comedy, tragedy and personal conquest have always been the bedrock of Korean TV dramas. The real spark in international interest in Korean dramas dates back to 2002 when KBS released “Winter Sonata,” which captured Japanese viewers’ hearts. The next year, the historical drama “Dae Jang Geum” (also known as “Jewel in the Palace”) captivated an even bigger overseas audience. Notable later hits include “My Love from the Star” from 2013 and “Crash Landing on You” from 2019.

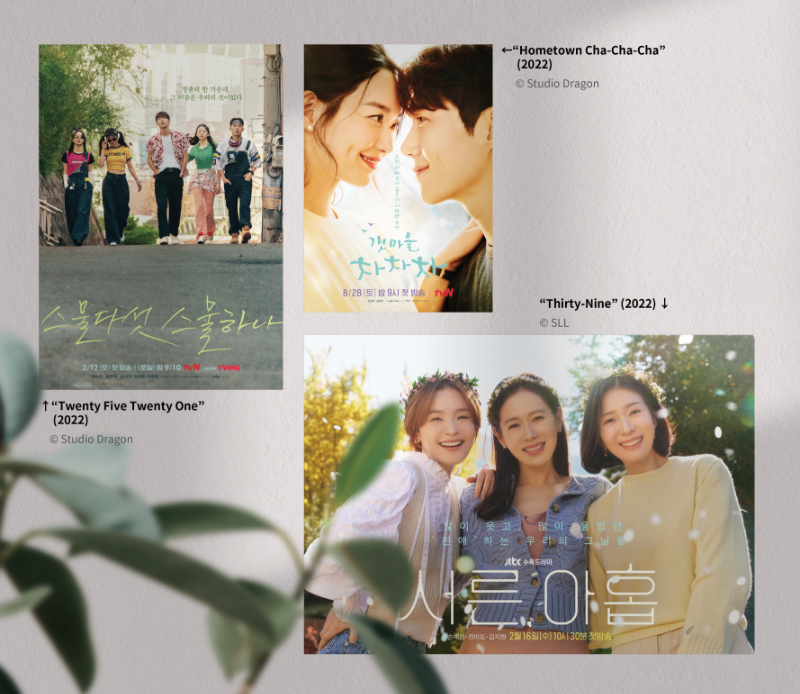

The right mix of elements generates mass appeal, though the buzz may not be so loud. When “Squid Game” became a global sensation in 2021, keeping viewers transfixed on the do-or-die competition, “Hometown Cha-Cha-Cha,” a romantic comedy set in a seaside village, quietly occupied Netflix’s Top 10 list in many markets. Likewise, when evil-doers and criminals in “Hellbound” were being sentenced, “A King’s Affection” was also parked in the Top 10, spinning romance in a fictitious palace.

Central to the nonviolent fare is conflict between the male and the female protagonists andtheir individual emotions, all expressed in a subtle manner. The emergence of global OTT (over-th-etop) streaming services such as Netflix have entrenched these dramas on viewer menus.

The two heroines in “Twenty Five Twenty One” start out as rival fencers but become best friends, cheering and supporting one another.

© Studio Dragon

New Label

The term now being used for the recalibrated genre is “K-melodrama,” or “K-melo.” On the surface, melodramas may not have changed much as they still deal with cliched love, but there are fundamental changes in tone and content. This change is driven by the generational transition in audiences. The main melodrama viewers are millennials and Gen Z, who collectively range in age from teens to the early 40s. They place a premium on work-life balance, much more than their parents’ generation did. Thus, K-melodramas are packed with nods toward attaining happiness, having enriching experiences and finding their sense of self through various relationships.

The overarching change is a nearly total absence of the damsel-in-distress trope, once typical of Korean dramas. The story of a knight in shining armor lifting a struggling woman up the social ladder is no longer appealing. Instead, viewers are more drawn to an equal relationship where the man and the woman share similar interests, values and lifestyles, finding true love at the end.

For example, the heroine in “Hometown Cha-Cha-Cha” is a dentist who escapes the turmoil of her career in Seoul and opens a practice in a seaside village. There she meets a handyman who is officially unemployed but much more complicated and educated than he seems. She falls in love with him, turning the usual worldly values on their head. “Our Beloved Summer,” which aired last year, was another hit with an atypical storyline. Two young people who were each other’s first love have to reconnect because of a documentary being made about them. The drama focuses on the emotions they share rather than the circumstances they are in.

“Thirty-Nine” is a romantic drama dealing with the friendship, love and emotions of threefriends soon to turn 40.

© SLL

“Hometown Cha-Cha-Cha” features a blossoming romance between a displaced city dentist and smart handyman, and their warm relationships with neighbors in a seaside village.

© Studio Dragon

Divergencies

What these recent K-melodramas have in common is that the protagonists do not obsess over success or wealth. Instead, they value relationships and the simple pleasures of everyday life. Global audiences can relate to dramas projecting such changed values as personal needs and priorities are questioned.

Different from the older generation whose lives mostly revolved around work, young Koreans want work-life balance. Gone are the days when a business card proved a person’s worth. The younger generation pursues happiness by doing something that they enjoy, usually irrelevant to their line of work. We can see this in “Hospital Playlist,” where the doctors unwind by playing in a band on the weekend. Rather than dreaming of succeeding as doctors, they’re happy doing the things they like.

Though melodramas once concentrated on the male-female relationship, they now increasingly focus on other types of relationships. In the past, the lens was typically fixed on women competing for Mr. Right. However, “Thirty-Nine,” which aired its final episode in March this year, focused more on the “womance” among the three heroines than on their romantic relationships with men.

Viewers want more than a love story from melodramas, some of which take on a new angle almost resembling that of a human drama. The recent “Twenty Five Twenty One” featured rival fencers, Na Hee-do and Ko Yu-rim, who end up being best friends and supporting each other. “Hometown Cha-Cha-Cha” also focused on community warmth and closeness, which is hard to find in today’s individualistic societies. And while in past melodramas the characters’ jobs were only in title and work scenes barely shown, recent dramas depict jobs in greater detail, giving insight into the characters and making them more realistic.