Landing in Korea 12 years ago to work on merger and acquisition deals, American Mark Tetto never imagined that an old house would change his life.

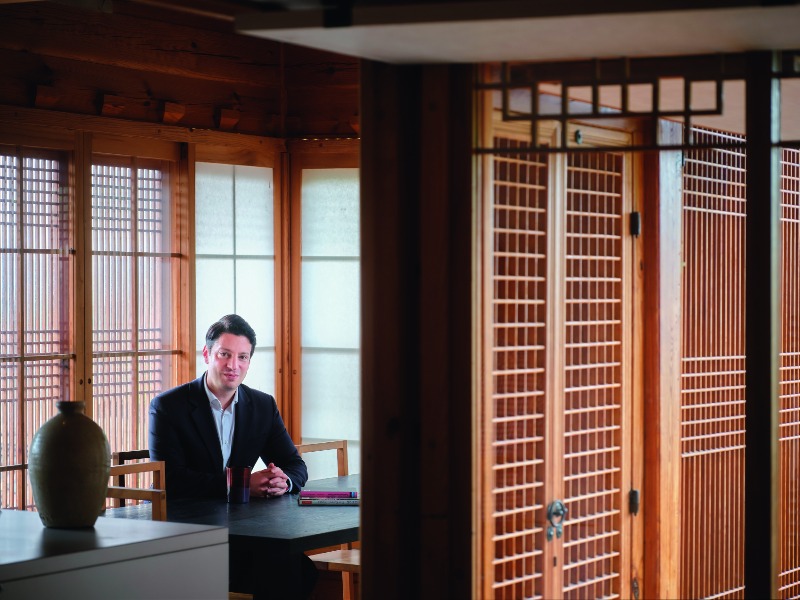

Moving into a hanok inspired Mark Tetto’s interest in Korean art and culture. Through his interviews with artists, he continues to learn about Korean ideas of beauty.

Mark Tetto may have been what Koreans see as the perfectly successful New Yorker: an undergraduate degree from Princeton University, an MBA from Wharton Business School, a Wall Street investment banking job at Morgan Stanley. It does make you wonder: why did he trade in that life and a Manhattan apartment for a new career in Korea and a hanok perched at the top of a very high, narrow alley in Seoul?

THREE GOALS, NEW TRACK

Soon after arriving in Korea, Tetto decided that no matter how long he stayed, he would work toward three goals: attain job expertise and perform well, learn the language, and make many interesting Korean friends from different industries. “Somehow I thought, if I did these three things well, then there would be some very interesting opportunities,” he says. And after five years things did start to happen. In a nutshell: “I changed companies, changed my house, and all of a sudden I was on TV.”

First, Tetto moved to TCK Investments, where he is now co-CEO. The company was formed by Ohad Topor who shared a similar vision: to do global finance from Seoul. While working in global investing, Tetto is also active in the venture capital industry.

Next, he moved to a new house, or rather an old house. One of the interesting people he had met was Nani Park, who had written a book about hanok and offered to show him some in Bukchon. “On a whim, I followed her here. I wasn’t looking to move but she showed me this house, and I ended up living here,” he says. Renovated to include a new basement area, the house is named Pyeonghaengje, meaning “a house where lives unfold in parallel.”

While all this was happening, Tetto was asked to appear on “Abnormal Summit” (a.k.a. “Non Summit”), the JTBC show that has f luent Korean speakers from various countries exchange views, giving insights into different cultures and ways of thinking. Sometimes, when the discussion turned to tradition, he ended up talking about his house. Thus, Tetto became engraved in viewers’ minds as a foreigner who is very knowledgeable about Korean culture.

In fact, Tetto had started studying up on old Korean furniture and art out of necessity. He realized that none of his old furniture and nothing he could buy in the shops was suitable for his hanok. “I thought, if I was going to live here, I was going to do it properly. I decided to learn about this space, and to do that, I thought I should learn about the Joseon Dynasty and what furniture people had in their houses,” he says.

FROM CONNOISSEUR TO COLLECTOR

What started out as a simple quest for a living room table turned Tetto into an art connoisseur, collector, writer, and lecturer. Eventually, he made the table himself, an octagonal piece inspired by traditional latticed doors. In the process, he mentally pictured other items for the house, thinking, “Should I put a bandaji [chest] here, or a dojagi [ceramicvessel] there?” He began visiting museums and doing his research.

“I first started studying Joseon baekja [white porcelain], and then you look further back to Goryeo celadon, and then even further back to Silla togi [earthenware]. You go back but then you go forward as well, which I didn’t expect. I might be researching online for a dalhangari [moon jar], and then all of a sudden the names of modern Korean artists come up, names like Koo Bohnchang and Ik-joong Kang. I found the pattern of white porcelain moon jars can appear in modern Korean art,” Tetto says.

So, Gorye Dynasty jar sits on the kitchen bench top, and coffee is served in colorful lacquered copper cups by Huh Myoung-wook. In the living room is a folding screen featuring Koo Bohnchang’s ethereal photographs of blue and-white porcelain. A piece of Silla earthenware adorns a Joseon wooden chest with a modern monochrome painting hanging above. From a wall closet, Tetto casually brings out an antique wooden lunchbox and an ancient unified Silla roof-end tile. Downstairs, he slides open the doors of the wardrobe he designed himself, revealing shelves and racks in a composition inspired by Joseon chaekgado (painting of a scholar’s bookcase), with his clothes hanging like curios. On the wall facing the bed in the guestroom is a photograph by Kim Hee-won printed on traditional mulberry paper, or hanji, showing latticed doors opening out onto the garden, as though extending the room and bringing the outdoors inside. Tetto’s collection is a mix of old and new, and every piece has a story. All of the modern pieces were made by people whom he met when interviewing artists for Living Sense magazine.

“Once you hear an artist’s story, that person’s work becomes much more meaningful. Now that work is not just an , it’s something that I have a relationship with,” he explains, giving his dishes by the potter Ji Seungmin as an example. “The plates are not just plates. I know this person. I met him and his wife before they married. They invited me to the wedding. So now there’s a story with these s.”

Over the past four years, Tetto has interviewed some fifty artists. This has given him a precious education on Korean art, and has led to opportunities to lecture on what he has learned.

Tetto’s hanok, named Pyeonghaengjae, is decorated with s just right for the house, including old furniture, ceramics, artworks old and new and even a table that he designed himself.

SECOND CHAPTER

When first asked to lecture on Korean art from a foreigner’s point of view, he asked himself “Am I qualified?” He pored over his interviews and house and found three common threads in both traditional and modern Korean art: yeobaekui mi, jayeonui mi and jeong. The best English approximations, respectively, would be “the beauty of empty space,” “the beauty of nature,” and human touch and warmth that, for want of a better word, is often translated as “affection.”

“As foreigners, we do see things in a somewhat different way. One point I can share is how amazing these things are to us,” he says. “I take a lot of joy in trying to get the word out about Korean art and artists. I didn’t go to art school nor did I study art or art history or art criticism. But meeting the artists one by one taught me a lot about Korean ideas of beauty.”

Tetto is now enjoying what he calls the “second chapter” of his life in Korea, and says, “The Mark of today is very different after five years of living in a hanok. Just sitting in this space was teaching me things and transforming me.”

Appreciative of the opportunities that have come his way, he has turned to philanthropy to give back to society. He joined Young Friends of the Museum, and together they raised money to purchase two precious Goryeo Buddhist artifacts from Japan, which they donated to the National Museum of Korea (NMK). On his own, he purchased 21 ancient Silla roof-end tiles (sumaksae) from an American collector, which also went to the museum. In addition to the NMK, he also supports the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) and the National Ballet.

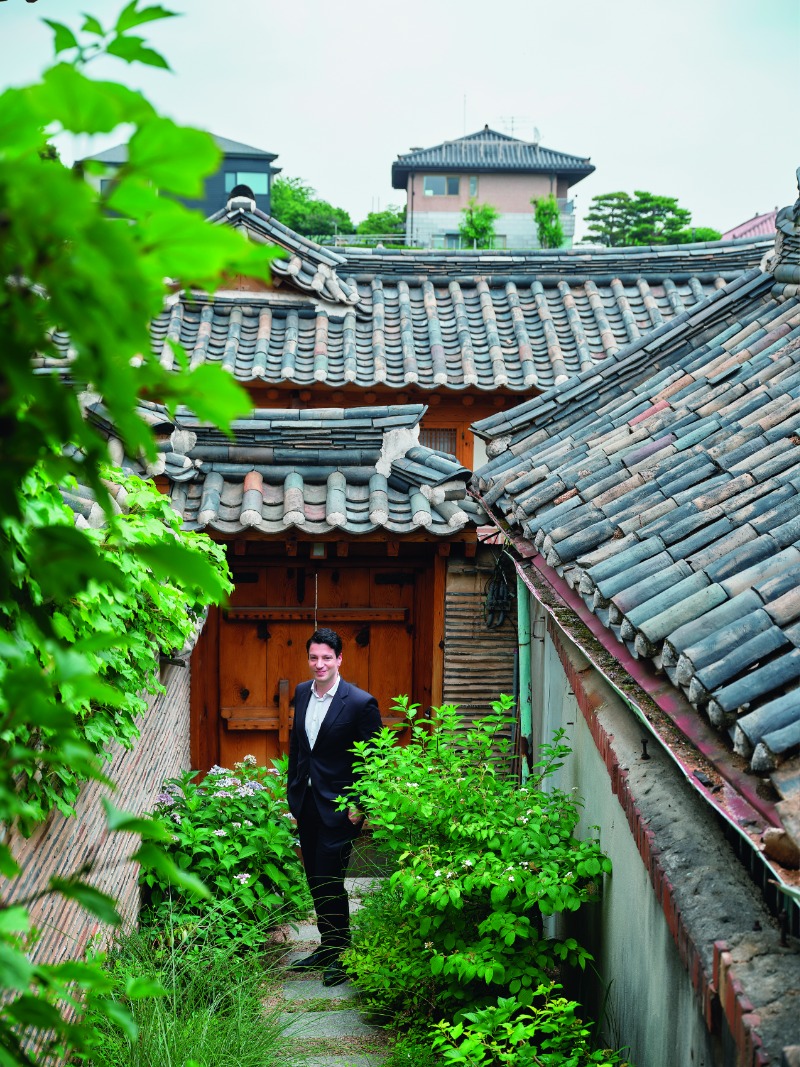

The flowers and plants lining the path leading from the front gate to the front door of the house enhance the beauty of the seasons

NEW PERSPECTIVE

This year, Tetto was asked to serve as ambassador for the Museum Week, held in mid-May. His role was essentially to encourage people to visit museums and art galleries by hosting a number of events and creating social media content. Though New York has some of the greatest museums in the world, he says he rarely went to them. But now museums, and an old house, have changed his life.

Tetto has 177,000 followers on Instagram, and the comments left there suggest his perspective on Korean art and culture has made many people take a second look at what is around them. As he walks home through the alleys from his office in Gwanghwamun, he basks in the sense of neighborhood. In his writings about Korean culture, he calls the alleys the face of Seoul, the place where the real life of the city takes place. And when he gets home, a Joseon Dynasty official on a hanging scroll in the entry (whose identity Tetto is investigating) watches over him as he takes off his shoes.

While many Koreans may have aspirations about New York, Tetto says, “It’s a very exciting and diverse life I’ve found in Korea. If I was in the U.S., I would mostly be doing my day job and going home. That would be it.” And probably sitting on furniture and eating off plates from Wal-Mart, he muses.

The portrait of a Joseon Dynasty official, who seems to be guarding the entryway, is thought to date to the early 20th century