Since first making inroads into Britain and the United States around the year 2000, Korean musicals and have seen remarkable success in Asian countries. Broadening their reach in the form of original productions, licensed musicals, joint ventures and investments, Korean musicals are poised to become the next frontier of Hallyu.

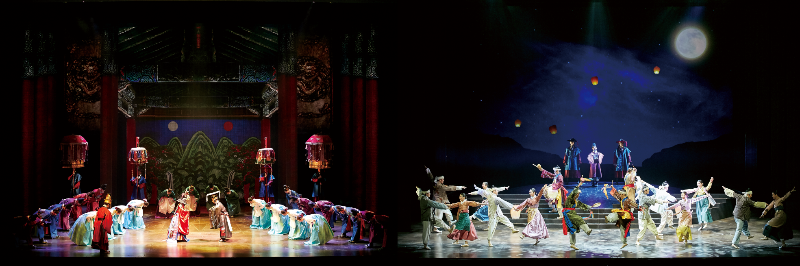

“The Last Empress” is a large-scale original musical that premiered in 1995 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Empress Myeongseong’s death. It is an epochal work, the first original Korean production to be staged overseas. The magnificent stage and elaborate costumes captivated global audiences.

© ACOM

Despite a series of setbacks resulting from a dampened economy and the coronavirus pandemic, Korea’s domestic musical industry has continued to grow and develop. Just prior to the pandemic, the size of the domestic performance market was estimated at around 400 billion won (US$316 million), with the majority of sales coming from musicals and concerts. Musicals are estimated to account for an average of 55-60 percent of this market, reaching 80 percent of total sales in 2021.

Since the unprecedented success of the Korean production of “The Phantom of the Opera” in 2001, the domestic musical industry has seen steady annual growth of 15-17 percent. In recent years, local production companies have made aggressive attempts to enter overseas markets to overcome the limitations at home, making new and innovative ventures that have brought stellar results in terms of quality, not just quantity.

Musical production houses began to turn their attention overseas around 2000. This dovetails with the time that licensed musicals started to take root in Korea, which stimulated an awareness of the need to reproduce or maximize the added value of this content.

Going Global

In the early years, original Korean productions mainly targeted the American and British market, namely Broadway and the West End, as well as performing arts festivals such as the famed Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Most notably, the original musical “The Last Empress,” produced by ACOM, and the non-verbal show “NANTA” were the first Korean productions to be staged on Broadway and the West End.

On the back of its successful premier run in Korea in 1995, “The Last Empress” was also performed at the David H. Koch Theater (then the New York State Theater) in Lincoln Center in 1997 and 1998. In 2002, it was staged in English at the Hammersmith Apollo on the outskirts of London. In many ways, it was an epochal work that demonstrated the commercial potential of original Korean musicals and also offered insight into what needs to be considered when breaking into overseas markets. For those in the performing arts industry dreaming of presenting their work to a global audience, it was a source of inspiration.

“Finding Mr. Destiny” is an original musical that was sold in 2013 to China, where the title was changed to “Finding My First Love.” This is a notable example of performance rights for a Korean production being sold overseas.

© CJ ENM

A scene from the Korean performance of “Finding Mr. Destiny.”

© CJ ENM

Posters (from left) for “Finding Mr. Destiny” in Taiwan, Japan and China.

© CJ ENM

Three Avenues to Overseas Markets

The tide turned in the 2010s when production companies began paying greater attention to the Asian market. In the first half of the decade, real expansion into Japan and China began. Japan fast became the main importer of Korean musicals, with some 40 shows being staged over three years beginning in 2012. Productions tailored to the Japanese market were boosted by the 2013 opening of Tokyo’s Amuse Musical Theatre, a dedicated venue for Korean musicals.

Korean musical content has entered overseas markets in three forms: tours of original musicals, Korean productions of licensed musicals and sales of performance rights of original musicals or joint productions involving local staff and investments. Tours of original musicals usually involve staging the show overseas for a set period with a Korean production crew and actors, and the lyrics translated via English subtitles. The jukebox musical “Run to You” was a hit with Japanese audiences during its run in Osaka in 2012 and Tokyo in 2014. Inspired by the songs of DJ DOC, a Korean hip-hop trio who debuted in 1994, it tells the story of three aspiring young singers.

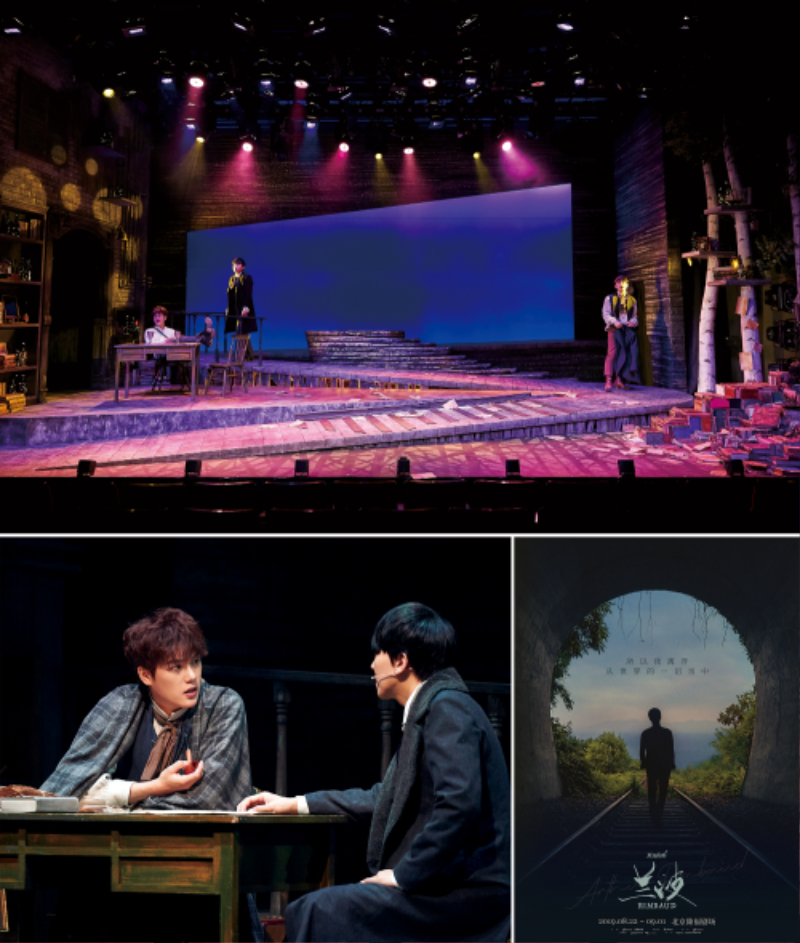

“Rimbaud” portrays the life of the French poet. A Korea-China project, the musical premiered simultaneously in both countries in 2018.

© LIVE Corp.

Likewise, after “Subway Line 1” debuted in China in 2001, the number of original Korean musicals staged in China increased each year. “Song of Two Flowers” (Ssanghwa byeolgok), which tells the story of two Silla Buddhist priests, Wonhyo (617-686) and Uisang (625-702), was invited to China in 2012 for the 20th anniversary of Korea-China diplomatic relations. The following year, it toured Shenzhen, Hainan, Guangzhou and Beijing, generating enthusiastic response. The show was adapted for the local audience, adding new characters and music inspired by traditional Chinese folk songs.

In the case of touring performances of licensed foreign musicals, shows are adapted and reinterpreted in Korean, and the Korean production is then re-exported to another country. Oftentimes, Hallyu stars are brought on board to promote the show. Some notable examples from the early 2000s are “Jack the Ripper,” “The Three Musketeers” and “Jekyll & Hyde” in Japan, and “Notre-Dame de Paris” and “Elisabeth” in China.

Finally, there are shows like “Finding Mr. Destiny,” the first original Korean musical to be adapted into a film, an example of performance rights being sold overseas. When the production was sold to China, the title was changed to “Finding My First Love” and the story adapted to better appeal to the sentiments and culture of the Chinese audience. It drew a considerable crowd upon its opening in 2013, proving the commercial potential of small theater musicals. Many other original Korean musicals have since made their way to China, including “Chonggakne Vegetable Store,” “My Bucket List” and “Vincent van Gogh.”

“Rimbaud,” which portrays the life of the French poet, was a collaborative project by Korea and China. d by the production house LIVE, which also brought “Chonggakne Vegetable Store” and “My Bucket List” to the stage in Japan and China, it premiered in 2018 in Korea and China simultaneously. The following year, the Beijing licensed reproduction was staged ahead of the Korean version. Another Korea-China co-production is “Feast for the Princess” by United Asia Live Entertainment, a production house jointly established by Korean entertainment conglomerate CJ ENM and China’s Ministry of Culture. It tells the story of chefs from around the world vying in a culinary competition toa dish to reawaken a princess’s lost sense of taste. Traditional Chinese cuisine was expressed through dazzling choreography and modern music.

“My Bucket List,” which questions the meaning of life, toured 23 cities in China, the most for any Korean licensed production staged in China.

© LIVE Corp.

Long-term Perspective

In 2019, just before the coronavirus pandemic, the Korean musical scene was greatly affected by political issues and international affairs.

Despite all the difficulties, the Korean musical industry is expected to continue to broaden its boundaries globally, with the potential to become the next frontier of Hallyu. The trend toward one source, multi-use cultural content means that Hallyu resources with proven global appeal will increasingly be brought to the stage. The unknown keys are who and which works will bring about a defining shift in the industry.

Won Jong-won Professor, Soonchunhyang University; Musical Critic