For many who come to Korea, teaching English is a brief stop on the road to something else. For Christopher Maslon, it became permanent. But he also thrives in art, his original pursuit, and dabbles in other areas, always ready to add to the things he loves to do.

© GEOJE CITY

When I heard the cherry blossoms were already in full bloom in the south, my heart, frozen throughout the winter, began to melt. I thought of a certain coastal road on Geoje Island and hurriedly packed, propelled by the thought that the thick tunnel of flowers might shed all its petals before I arrived.

I was in my car before sunrise and relieved to have a large cache of music for the road. The GPS informed me that the drive from Seoul would take about four and a half hours – six if I stopped at rest stops. Of the songs on my playlist, I’m especially fond of “Gran Torino.” It’s about driving a Gran Torino, a U.S. muscle car of the 1970s, to console a tired and lonely heart.

Engines hum and bitter dreams grow

Heart locked in a Gran Torino

It beats a lonely rhythm all night long

The song is part of the soundtrack of the movie of the same name. The protagonist, played by Clint Eastwood, is a grumpy, aloof Korean War veteran whose trauma makes him wary of letting people get too close. When I listen to it, it feels like my car has also become a Gran Torino, comforting me while taking me to Geoje Island.

Pow Memorial Park

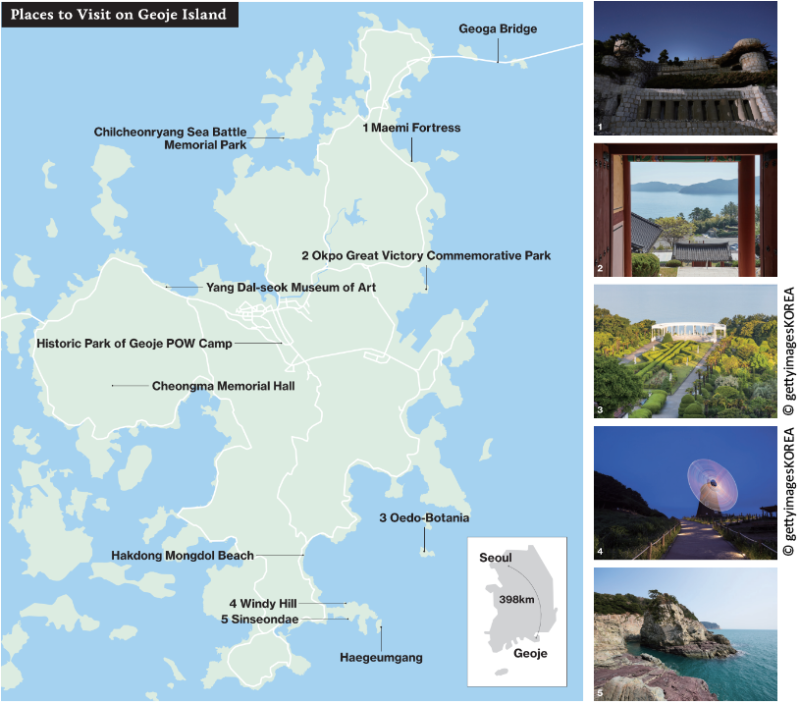

With the completion of the Geoga Bridge, the travel distance between Busan and Geoje Island was dramatically reduced from 140 km to 60 km and the travel time from 2 hours and 30 minutes to 30-40 minutes.

© gettyimagesKOREA

Geoje Island lies between the city of Busan to the east and Tongyeong to the west. Although an island, it has long been accessible by land thanks to Geoje Bridge, completed in 1971, and beside it the New Geoje Bridge, completed in 1999. Both lead to Tongyeong. In 2010, an overland road to Busan also opened when Geoga Bridge, an 8.2-kilometer bridge-tunnel, was built to the east.

The bridges connecting Geoje to Tongyeong span a narrow waterway famous for its many reefs and fierce currents. In 1592, during the first Japanese invasion of Korea, Admiral Yi Sun-shin lured the enemy here and off Hansan Island. His outnumbered warships moved into crane wing formation and routed the Japanese fleet. But no matter how thrilling this sounds, there is a more sobering side to Geoje Island: its history as a holding pen for tens of thousands of war prisoners.

In September 1950, the Incheon Landing led by General Douglas McArthur bisected North Korean forces, reversing the tide of the Korean War. With their supply lines cut off and their ability to repel counterattacks crippled, North Korean soldiers ended up in a 12,000 square meter prisoner-of-war (POW) camp in the Gohyeon and Suwol districts of Geoje Island. The camp began operation in February 1951 with 150,000 North Korean soldiers, 20,000 Chinese Communist soldiers and 3,000 militia soldiers. Among them were 3,000 female prisoners.

The Historic Park of Geoje POW Camp memorializes those captured in war. As soon as I stepped inside, I came across the text of the Geneva Convention, a set of treaties that established international legal standards for humanitarian treatment during wartime. The 1949 agreements in particular define the basic rights of prisoners of war. They were applied for the first time during the Korean War.

The exhibition hall at the entrance of the Historic Park highlights efforts to protect the human rights of the North Korean POWs. It is said that the meals served at the camp were much better than the food given to soldiers at the frontline. Still, regardless of how well the POWs were treated, their agony was inescapable as the war grinded on. Locked up with no idea of how far from home they were, they spent their days as forced laborers. Sometimes, for propaganda purposes, they were forced to act as if they were content despite their circumstances.

Displays of the barracks, uniforms and other materials that shed light on the lives of prisoners make the Historic Park of Geoje POW Camp an educational site and tourist attraction of Geoje Island.

The movie “Swing Kids,” set in 1951 during the Korean War, follows a tap dance team that is assembled to perform at the largest prisoner-of- war camp in South Korea, on Geoje Island.

© NEW

A photograph of prisoners at the Geoje camp doing a folk dance inspired Choi Suchol’s 2016 novel “Dance of the POWs” (Porodeului chum ). On the same subject, theater director Kim Tae-hyung staged the musical “Ro Gi-su” (2015), later adapted by the movie director Kang Hyoung-chul into the movie “Swing Kids” (2018).

Did the prisoners learn, practice and perform the dance in the photograph of their own volition?

In one photo taken in 1952 by Werner Bischof, a member of the internationally renowned photojournalist group Magnum, the prisoners are wearing unusually large masks as they dance in their camp. Presumably, they wanted to hide their identity to avoid attacks by fellow prisoners who felt betrayed, or perhaps to protect themselves and their families from eventual government persecution in North Korea if the photos were seen. This theory is reflected in “Dance of the POWs,” “Ro Gi-su” and “Swing Kids.”

Pebbles that resemble black pearls blanket beaches on Geoje Island. The sound of the water washing over the pebbles when the tide goes out (described as “jageul jageul”) has been selected as one of the top 100 natural sounds of Korea.

© gettyimagesKOREA

One might ask what more could be done for people who once pointed their guns at “our side.” Coming from a generation that has never experienced war, I have nothing to say on such a sensitive issue. I can only hope with all my heart that war and similar threats and violence will disappear from Earth.

I turned toward nearby Chilcheon Island, where most of the Korean fleet was destroyed in 1597. It was the only major defeat of the Korean Navy among countless battles against Japanese warships. Before the battle, Admiral Yi Sun-shin had been removed as naval commander because he disagreed with King Seonjo over strategy. Standing in the yard of the memorial hall, I sighed, then sighed again as I looked down at the water. Some 20 minutes away is Okpo, the site of Korea’s first naval victory against the Japanese under the command of Admiral Yi during the Imjin War. A truce was declared after the initial invasion in 1592, and then a second invasion in 1597. The next year, Japanese forces finally withdrew from the Korean peninsula. My Gran Torino continued on to the next traces of war.

Mongdol Beach

Haegeumgang, an island that features two rocky peaks, is found within Hallyeohaesang National Park. The sun rising over Lion Rock is a spectacular sight that appears only in March and October

© gettyimagesKOREA

Geoje Island is home to many beaches covered with pebbles (mongdol ). One of them is the 1.3-kilometer long Hakdong Mongdol Beach on the southeast side of the island. This beach has no sand. Instead, it’s covered with smooth “black pearl” pebbles of various shapes and sizes.

Pounding ocean waves eroded and fragmented large rocks into pebbles the size of a fist. If one paused to consider how long it took for small pebbles to be d, life would seem to last for no more than a fleeting moment. Hakdong Mondol Beach, shaped like a flying crane, is the most famous pebble beach on the island, attracting a steady stream of tourists all year round.

Wherever the waves wash over the smooth black pebbles, they glitter in the sun, looking exactly like black pearls. Covering the beach, they rub loudly against each other whenever the seawater rushes in. In this fashion, the raw power of the waves is scattered. Unlike sandy beaches, pebble beaches protect residents who live by the seaside.

According to local folklore, all the pebbles on the beach disappeared one day when the waves were particularly fierce. Only sand was left, and the residents trembled with fear at this strange occurrence. But the next day, like magic, all the pebbles were back. This little tale speaks of how much the locals love and treasure the black pebbles, and indeed, efforts are made to stop tourists from pocketing one or two of them as souvenirs. To that end, the account of an awakened American teenager appears on the signboards on every pebble-covered beach:

In the summer of 2018, a small package arrived at the eastern branch office of Hallyeohaesang National Park. Inside were two black pebbles and a letter. A 13-year-old American girl had taken the two pebbles home as a souvenir, but felt they should be returned. “My mother found out later and taught me how long Mother Nature had labored to make these beautiful stones. So I decided to give back the pebbles to their rightful place,” the girl wrote in a letter of apology. Her sincerity is sure to have greater impact on would-be souvenir hunters than any warnings of fines or penalties.

After strolling along the beach I boarded a ferry. I wanted to see Haegeumgang, an island consisting of two rocky peaks whose name means “diamond of the sea.” Sticking straight up in the middle of the water, the island was designated as Scenic Site No. 2 back in 1971. Of Korea’s 129 nationally designated scenic sites, only 15 are marine or insular sites, and two of these are found in the Geoje district of Hallyeohaesang National Park – an indication of the great beauty of the coastal scenery around Geoje Island. Near Haegeumgang is Sinseondae Observatory. A long stairway off the coastal road leads to the viewing site, overlooking cobalt waters and rocky terrain ed in blue and yellow.

Artist of Geoje Island

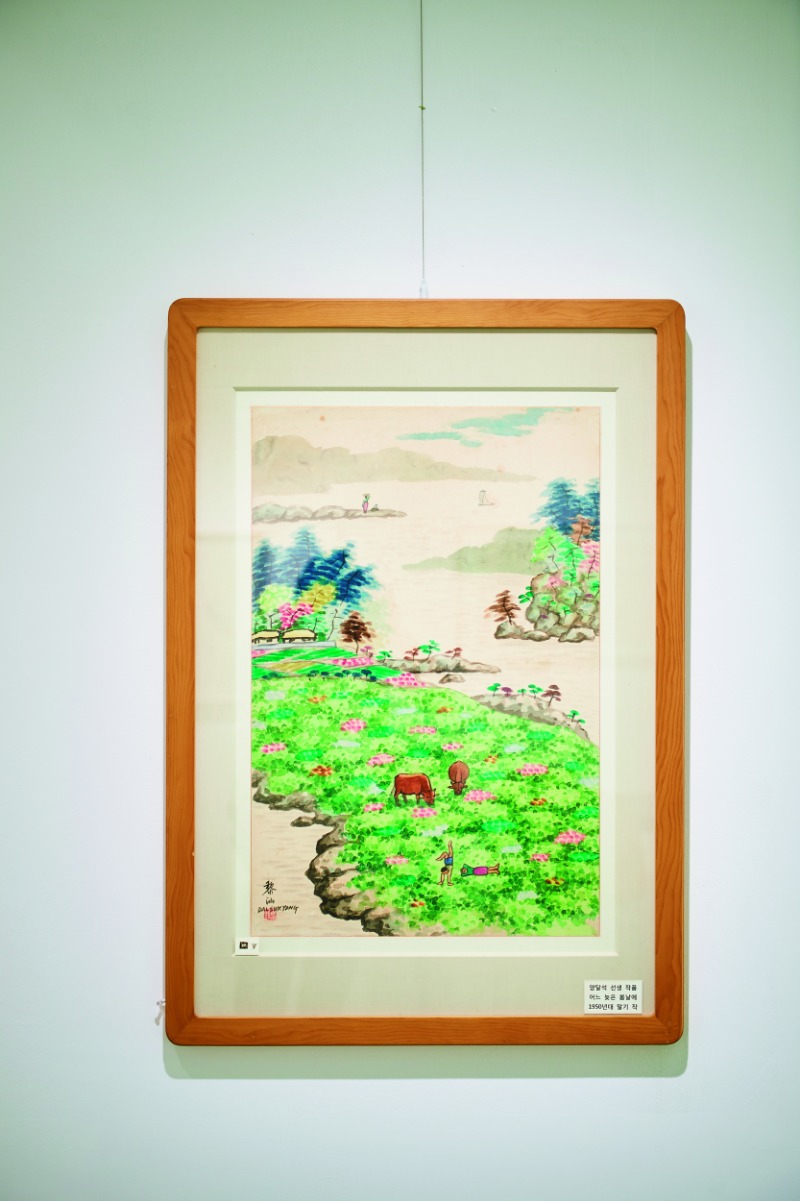

Yang Dal-seok (1908-1984), famous for his idyllic, innocent paintings of the Korean countryside, was called the “painter of cows and herders.”

Cheongma Memorial Hall was built at the birthplace of Yu Chi-hwan, a leading figure in modern Korean literature. The building houses records related to the life and work of the poet, whose penname was Cheongma, meaning “blue stallion.”

With the glories of Haegeumgang engraved in my memory, I returned to port and hit the road again – this time to meet Yang Dal-seok (1908-1984), one of Korea’s earliest Western-style painters, and Yu Chi-hwan (1908-1967), a major name in Korean poetry. Is it possible that the two artists turned into the towering rocks of Haegeumgang after they died?

I first headed to Seongnae, the hometown of Yang Dal-seok. Entering the village filled with murals that replicate his paintings was like entering a storybook. Many of these paintings feature cows and shepherds, with children happily running around though their pants are falling down, clearly revealing their buttocks. Some are doing handstands while others are bent over and looking at the world from between their legs. Their behavior and s are expressed comically. Cows are lazily chewing on grass and the whole world is green and fresh. Everything is peaceful. How could the world painted by Yang be so lyrical and beautiful?

Orphaned at a young age, Yang spent part of his childhood as a servant at his uncle’s house and was familiar with cows. One day, he lost a cow that he had taken out to pasture and received a severe scolding. That night, he scoured the mountains.

When he finally found the cow, he held onto one of its legs and wept. Perhaps painful memories such as this turned him into an artist who dreamt of a world without fear or worry.

At Cheongma Memorial Hall I encountered another artist born on Geoje Island who had dreamt of paradise. Real life may have been grueling for the poet Yu Chi-hwan, but in his works, he never lost hope or determination. His most famous poem, “The Flag” (Gitbal), describes a fluttering banner. It contains a phrase that every Korean has heard at least once: “the voiceless outcry,” used in every literature class as an example of paradox.

Another of his poems, “Geojedo, Dundeokgol,” extolls his birthplace. It is inscribed on a monument that stands in the yard of the memorial hall. Over several lines, the poem brings to life the harsh conditions of his hometown, but in the last line, the poet vows not to abandon it. He promises “to pass after living a benevolent life, tending the fields at sunrise.” It reveals a persona that was unusually easy and tolerant. Yu’s penname was Cheongma, or “blue stallion,” which in my imagination roams the fields and mountains of the island.

Engines hum… My footsteps began pointing toward home. Singing to myself as I always do, I asked myself what kind of promise I could make. Do I have even a pebble’s worth of ease and tolerance? Engine humming, my Gran Torino gave me the answer: don’t be tied down even by such questions.

Kim Deok-hee Novelist

Han Jung-hyun Photographer