After the Korean War ended in a ceasefire, establishing the Military Demarcation Line separating the two Koreas, American troops remained in the South. The U.S. military presence gave rise to a burgeoning live entertainment industry catering to these servicemen living away from home. Korean musicians who stood out at the “Eighth Army shows” later became mainstream acts pioneering trends in Korean popular music.

Hollywood star Marilyn Monroe performs for American and UN troops stationed in South Korea. During her four-day visitin February 1954, Monroe gave 10 performances at military camps across the country, including those in Seoul, Dongducheon, Daegu and Inje County. Braving sub-zero weather, she went on stage in a tight, strappy dress and dazzled her audiences.© gettyimages

The global popularity of K-pop beyond Asia has provided some food for thought. What about K-pop has made it so immensely popular worldwide? What is the cultural potential of a country where music with such a far-reaching impact originated? How did this music evolve to become what it is today? The most fundamental question, however, would probably be about its beginnings.

One common view is that K-pop originated from the Eighth U.S. Army shows that were staged in Korea in the 1950s. According to this perspective, contemporary popular music in Korea was strongly influenced by the American popular music that entered the country through these shows. This, in turn, gave birth to open auditions for discovering new talent, as well as to professional agencies for entertainment management.

Such claims, if not entirely unfounded, are probably an oversimplification. There is a 30-year time gap between the U.S. Army camp shows and K-pop as we know it, and the journey that Korean popular music took during those years bears as much significance as the changes that those shows brought to Korea’s pop music scene.

Presence of U.S. Troops

The 20th century was peppered with wars, all-out endeavors that mobilized massive troops and resources. Around the start of the century, governments began to provide military entertainment to boost the morale and patriotic spirit of their servicemen. The U.S. government laid out plans to supply live entertainment to the soldiers on the front lines during World War I, and these plans came to fruition during World War II in the form of the United Service Organizations (USO), a non-profit entity. During and after the Korean War, big names in American entertainment, such as Marilyn Monroe, Louis Armstrong and Nat King Cole, to name a few, visited South Korea for USO tours.

In actuality, the Korean entertainment industry had already begun catering to the U.S. military stationed in the country. After the nation’s liberation from Japanese rule in 1945, a U.S. military government was temporarily set up in Korea; the 24th Army Corps administered the southern half of the peninsula, creating demand for live entertainment at its camps across the country. At that time, there were quite a number of local show troupes and entertainers in Seoul who had been active since the colonial era. Most were well versed in Western popular music such as the Latin, chanson and jazz genres which had been permeating Korean urban centers since the 1920s.

In the early days of the U.S. Army camp shows, the busiest act was Kim Hae-song (a.k.a. Kim He-szong) and his band KPK. Kim was widely known as the husband of singer Lee Nan-young and father of Sook-ja “Sue” Kim and Aija Kim, two of the three members of the Kim Sisters (see box on page 14). Kim started his career as a singer-cum-composer in 1935 and achieved fame as one of the best jazz musicians in Korea.

The camp club shows really took off when the Eighth U.S. Army headquarters was relocated from Japan to Yongsan, Seoul, and the United States Forces Korea (USFK) was established in 1957. Army camps were set up around the country, including at Yongsan in Seoul, Pyeongtaek and Dongducheon in Gyeonggi Province, and Daegu in North Gyeongsang Province. Clubs for U.S. servicemen sprouted up around these camps; in the mid-1950s, the number of these clubs in the vicinities of Seoul and the Demilitarized Zone alone reportedly totaled 264. The surging demand for live entertainment at these establishments could no longer be met with sporadic shows by Korean entertainers or celebrities invited from the United States.

The first local entertainment agency, Hwayang, opened in 1957, and was followed by Universal and Gongyeong. These businesses employed a structured approach to managing and training talent, prepping for auditions and organizing live music events. In a war-ravaged country, the U.S. camp club shows were a jackpot that guaranteed huge profits. The USFK shelled out an average of US$1.5 million annually to local entertainers in the early 1960s. The entertainment agencies grew rapidly. A 1962 newspaper article reported how these companies set up by “vagabond showmen” had expanded to command some 1,000 entertainers belonging to 25 troupes and 60 bands.

American-Style Shows

Competition intensified as more and more entertainers sought opportunities in the U.S. camp show circuit. Open auditions were held every three to six months in front of American judges dispatched by the U.S. Department of Defense. Candidates were assigned grades that would determine their pay and the shows they could do. Those rated AA were guaranteed high incomes, while others in lower grades were shuttled from one camp to another in rural regions on the back of military trucks. D was a failing grade.

The auditions were introduced by the U.S. military to control the quality of the shows, but their requirements served as de facto rules for local entertainers. Only certain types of music, performances, sounds and manners were encouraged, and anything else was forbidden. Korean-style music and originality were rejected; conversely, the more closely American-style music was emulated, the bigger the reward. “Good English pronunciation,” “ability to convey emotions naturally and attractively” and “good showmanship” delineated the criteria, and Korean performers had to internalize American entertainment, changing their techniques and practices accordingly.

Although they weren’t able to perform their own music, the Korean entertainers took great pride in their job.

The American-style popular music they played in the U.S. Army clubs was generally perceived as urbane and refined.

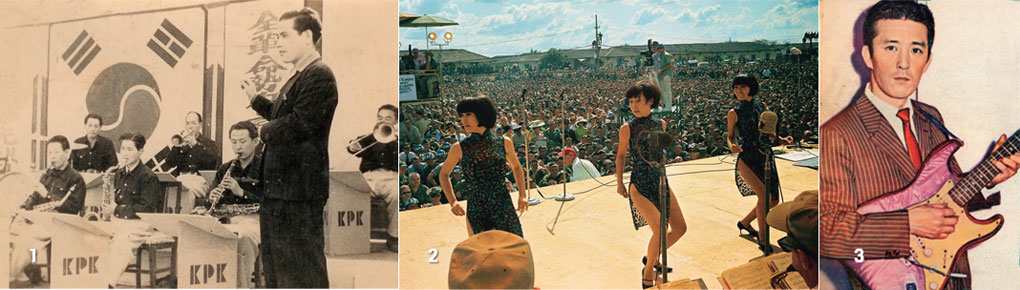

1.Kim Hae-song (1911-1950?) performs with his band KPK, which he formed in 1945 shortly after the nation’s liberation from Japanese rule. Kim and KPK were a regular act in the Eighth U.S. Army shows, mostly performing Korean folk songs arranged in jazz style. © Park Seong-seo

2.The Korean Kittens perform for American servicemen in Bob Hope’s 1966 USO Christmas show held in Tan Son Nhat, Vietnam. Yoon Bok-hee (1946- ; center),the leader of the group formed in 1964, made her debut at a young age in the Eighth U.S. Army shows and went on to become a huge star. © AP Photo by Horst Faas

3.A photograph of Kim Hui-gap (1936- ), a famous composer who produced numerous hits, from the late 1960s. Kim started his career in 1955, straight out of high school, as a guitarist in the Eighth U.S. Army shows. © Kim Hyeong-chan

Versatile Talents

In the early days, the shows mostly consisted of popular jazz songs and Korean songs arranged in jazz style. But after the audition system was introduced, the repertoires were entirely made up of American popular music with the exception of a few famous Asian songs, such as the Korean folk song “Arirang” and the Japanese pop song “China Night.” To pass the auditions, musicians had to learn and practice the latest American pop songs from jukeboxes at the military bases, AFKN (American Forces Korea Network, known today as AFN Korea) radio, and stock arrangements of American music or songs found in “The Song Folio.” Thus, the Korean entertainers gradually became “culturally American.”

The Eighth U.S. Army shows also became specialized to meet the demands at diverse clubs for different clients, such as those exclusively for officers, non-commissioned officers or enlisted men; white clubs and black clubs; and service clubs and general clubs. Service clubs were like large concert halls while general clubs were smaller venues where sales of alcoholic beverages were permitted. The preferred styles of music depended on the audience: clubs for officers where most of the patrons were white and over 30 largely played standard pop, semi-classical or jazz, while rock and roll, jazz, rhythm and blues, or country music were performed at clubs catering to non-commissioned officers and enlisted men.

Korean entertainers had to become skilled in all musical genres, for specializing in one particular genre meant fewer opportunities. That was the nature of the U.S. Army show circuit, which functioned as a kind of substitute for American culture, inspiring patriotism in the servicemen and soothing their homesickness. Consequently, local musicians were required to become human jukeboxes – anonymous faces conveying the sounds and sensibilities of a far-off homeland. To expand beyond imitation, they would need a different stage.

The heyday of the Eighth Army shows lasted from 1957 to 1965, when the United States significantly scaled down its military presence in South Korea due to the Vietnam War. During this period, American pop music trends shifted from swing jazz and standard pop to rock and roll. The Eighth Army shows quickly caught on, producing numerous Elvis Presley and Beatles cover acts.

Compressed Growth

Although they weren’t able to perform their own music, the Korean entertainers took great pride in their job. Among them were more than a few college graduates, which was uncommon for popular musicians at that time. The high pay and “advanced” American culture appealed greatly to them, and the American-style popular music they played in the U.S. Army clubs was generally perceived as urbane and refined. On the other hand, homegrown teuroteu (trot) music, which was popular mostly among rural residents and the urban working class, was given the derogatory name ppongjjak. In the meantime, American-style popular music moved to the mainstream as private TV networks, established in the mid- to late 1960s, recruited entertainers from the Eighth Army shows in large numbers.

Further study is required to precisely gauge the impact of the transition to American-style pop music at that time on today’s K-pop. Like the music of many other countries that have gone without a U.S. military presence, Korean popular music would likely be little different from what it is today without the influence of the U.S. Army club shows. Nonetheless, those shows should be credited for shortening the development process of Korea’s popular music. And it’s certainly interesting to note that “compressed modernization,” a symbolic catchword of Korea’s social and economic growth, can also be witnessed in the trajectory of the nation’s popular music scene.

The Kim Sisters WowLas Vegas

Zhang Eu-jeong Music Historian; Professor, College of General Education, Dankook University

Scores of appearances on major TV shows, such as “The Ed Sullivan Show,”“The Dinah Shore Show” and “The Dean Martin Show.” The first Asian girl group to perform in Las Vegas. These are some of the legendary feats of the Kim Sisters, a Korean female trio who were active on the U.S. entertainment scene – and all of this some 60 years before BTS would achieve breakthrough success in America. The group consisted of sisters Sue (Sook-ja) and Aija Kim and their cousin Mia Kim. Sue and Aija’s parents were acclaimed musicians – composer Kim Haesong and singer Lee Nan-young – while Mia’s father was Lee’s elder brother, composer Lee Bong-ryong. The Kim Sisters began their career in 1953 performing in shows for the Eighth U.S. Army, providing entertainment to American servicemen stationed in South Korea. Not only were they talented vocalists and dancers, they played a variety of instruments. They were such a huge hit with the American troops that they were invited to perform in the United States in 1959.

In 2016, the centenary of the birth of Lee Nan-young, I had a chance to sit down for an interview with the group’s leader, Sue Kim, in Mokpo, Lee’s birthplace and the settingof her monumental song “Tears in Mokpo.” The following is an edited transcript of that interview.

The Kim Sisters in 1970, when they gave a homecoming show at Seoul Citizens’ Hall. It was their first visit to Korea in 12 years. Their four-day show was a huge success. From left: Mia, Sue and Aija Kim. © Newsbank

How was the group formed?

After my father was abducted to North Korea in 1950, during the war, my mother started doing solo acts on the Eighth Army stage to earn a living. But it became too grueling to do on her own, so my big sister Yeong-ja and I joined her. I remember singing Spanish songs while tap dancing. Then, as Yeong-ja had a sudden growth spurt, my younger sister Aija and cousin Mia took her place. That’s how we became the Kim Sisters.

When did you start taking music lessons and what did you learn?

Our father gave us music lessons from a young age. I think it was when I was six; he would appear suddenly from nowhere and shout, “One, two, three!” and all seven of us siblings would immediately have to sing in a round or in harmony. He didn’t spare the rod if we made a mistake. He loved us very much and was very proud of us. But he wasn’t an affectionate father and was strict with us.

My mother was very different. To prepare us for shows, she would first learn the songs herself and was very thoughtful and attentive as she taught them to us. When we were rehearsing, she used to have a basket covered with a white cloth that was filled with fruit like bananas, which were hard to come by back in the day. She promised to give us one only when we learned a new song, which made us work harder.

The Kim Sisters and Lee Nan-young (19161965; center) when they appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1963. © Newsbank2

The leader of the Kim Sisters, Sue, plays the mandolin during an interview with the Dong-A Ilbo at her home in Henderson, Nevada, in 2018. © The Dong-A Ilbo

When did you first go to the United States and what was the response?

My mother signed a contract with an American agent, named Tom Ball, in 1958. But instead of going straight to America, we went to Okinawa, Japan that winter to give a performance for American soldiers there. We flew to Las Vegas in January 1959. It was a four-week contract, but we gave it our all because we felt we couldn’t go back to Korea. Luckily, our first show was an instant hit and our contract was extended. We were even invited to perform on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” In total, we made 22 appearances. I was in charge of selecting and arranging the songs as well as the costumes.

Your mother must have been worried, sending her young daughters to a faraway country. What advice did she give you?

She said two things to us. First, “get along”; second, “don’t date.” She wanted us to get along well and look out for each other. She told us to avoid men because if a guy entered the picture, the group could break up. We’d never had boyfriends before in Korea, and we really had no desire to date men in America.

Is there anything in particular that you remember about those days in America?

For one, we were homesick for Korean food. Work conditions weren’t that great back then. After we did a performance, we would rest briefly on a bed next to the stage and then perform again. One day, Aija broke down crying because she wanted to eat kimchi so badly. So we had some sent to us from Korea, which took ages to arrive. When I went to collect the package, it wasn’t there. Apparently, someone had thrown it away because the juice had leaked all over. I remember grumbling to myself, “That means the kimchi was fermented just right.”

What happened after the Kim Sisters?

Aija got married in March 1967, followed by Mia in April. I felt so alone. Then I met my husband, John, and got married the following April. He was a big fan who had come to see our shows eight times. The Kim Sisters disbanded in 1973; in 1975, my big sister Yeong-ja joined and we started doing shows again, which lasted for 10 years until 1985. After Yeong-ja left the group, Aija and I formed the Kim Sisters & Kim Brothers with our younger brothers Yeong-il and Tae-seong. When Aija passed away from cancer in 1987, we regrouped as Sue Kim & Kim Brothers. Then I injured my back in an accident in 1994. Starting a new chapter in my life, I decided to study for the real estate license exam. I failed seven times and passed on my eighth try. I’ve been working in real estate for over 20 years now. I have two children, Anthony and Marisa, and five grandchildren.

Lee Kee-woongHK Research Professor, Institute for East Asian Studies, Sungkonghoe University