Jeong Yak-yong dreamed of Joseon’s renaissance with the reform-minded King Jeongjo, applying critical intellect to the humanities, science and various other fields of endeavor and advocating practical action. This year marks the 200th anniversary of Jeong’s completion of his seminal work “Admonitions on Governing the People” (Mongmin simseo) as well as his release from 18 years in exile. Although over 180 years have passed since his death, it seems his heart remains by Chocheon, the little stream that runs along his home village.

The North and South Han rivers meet at Dumulmeori in Yangpyeong County, Gyeonggi Province, and flow into the Han River. The area lost its function as a transportation hub for people and goods, but it still produces a dawn mist that inspires artistic works.

Mist covers theof one’s gaze, making it hazy. But the view is not completely obstructed. Eyes still rest on a spot between what is revealed and what is not. Aesthetic curiosity is aroused when balance is achieved between the parts that are transparent and honestly revealed and those that are half-concealed. Dumulmeori, seen from Sujong Temple, has always been a famed destination of poets and artists who wanted to recite a few verses about the lovely, clean vastness of the Han River spread out below them or to capture the scenic expanse with their brushes. Today it is a favorite panorama of amateur photographers.

Ancient Temple and Morning Mist

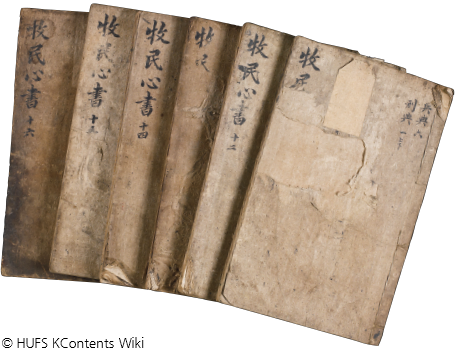

This year marks the 200th anniversary of “Admonitions on Governing the People” (Mongmin simseo), one of Jeong Yak-yong’s most important works. The 48-volume book is highly acclaimed for its criticism of the tyranny of government officials and suggestions on how local magistrates should serve the people.

Dumulmeori (literally “head of two waters”) is a name commonly used for a place where two bodies of water join. Here it refers to the southern part of Yangsuri in Gyeonggi Province, where the North Han River meets the South Han River. An hour’s drive from Seoul, past Hanam and across the Paldang Bridge, brings you to this quiet place with wide-open vistas of the rivers and the mountains. It is the perfect weekend destination for residents of the capital and couples on a date. A further 300-meter hike up a steep path on Mt. Ungil leads to Sujong Temple, which affords the view of the two rivers flowing into the Han River below.

Dumulmeori had a ferry landing that was on the route connecting Jeongseon in Gangwon Province and Danyang in North Chungcheong Province with the ports of Ttukseom or Mapo in the capital. But when Paldang Dam was built in the lower reaches in 1973, this historic place completely lost its function as a watercourse. The dam caused the river to widen and the current to slow down, turning it into a lake-like environment with groves of reeds and rushes, lotus blossoms and water caltrop - aquatic plants that thrive in still water. Taking advantage of this change in the ecological environment, wetland parks have been d by the riverside with diverse facilities and sculptures installed, namely Semi Garden and Dasan Ecological Park, which are crowded even on weekdays.

When Jeong Yak-yong was released from exile, he returned to Majae, his home village in Namyangju, Gyeonggi Province, and lived there until his death. He had dreamed of spending his life fishing in his hometown.

The highlight is morning mist. At dawn, when the temperature difference between the water and the land widens, mist rises without fail over the gentle water surface. First arising from Lake Cheongpyeong, then wrapping itself around the s of mountains, the mist finally descends on the Dumulmeori riverside as daylight begins to shine, offering a breathtaking sight. Anyone fortunate enough to encounter this misty daybreak would stop in their tracks, as if caught inside a memory that has been converted into an old landscape. If you have seen the sun rise over Dumulmeori from Sujong Temple, one of the finest views of the Han River, you’ll find yourself stopping by the small café near the parking lot on the way down and exchanging a few words with the woman who runs it. She will show you a few photos on her phone, the enigmatic views of Dumulmeori that brought her to this place.

When the 22-year-old Jeong Yak-yong (1762-1836; pen name Dasan, meaning “Tea Mountain”) passed the lower-level civil service exams in the spring of 1783, he traveled to Sujong Temple with ten companions. It was a way to congratulate himself and also to comply with his father’s wish that he visit home with his friends in a “not too shabby” manner. It had been seven years since Jeong left home for Seoul, after marrying at the age of 15, to study for the state exams, and over those years his father would have had deep worries. In addition, by coming home in this fashion, Jeong would have wanted to boost solidarity among the Namin, or the Southerners, the political faction to which his kin belonged.

An ancient place more than a thousand years old, Sujong Temple sits in a beautiful natural setting, not far from Jeong’s home village of Majae (“Horse Hill”). When he was young, Jeong often visited the temple to read and compose poetry. On his visit there after passing his exams, he asked for liquor when the moon appeared and wrote poetry, relishing “the joy of returning as an adult to a place where you played as a child.” He recorded the events of that day in a simple volume titled “Excursion to Sujong Temple” (Sujongsa yuramgi).

The Bicentenary of Release from Exile

Compared to his contemporaries, Jeong Yak-yong was as much admired in Korea as Johann Gottlieb Fichte in Germany and Voltaire in France. He left behind a vast collection of books and other writings, the output of a critical mind ahead of its time promoting the practical use of statecraft (gyeongse chiyong). In 2012, Jeong Yak-yong was one of the world’s great figures honored under UNESCO’s “Celebration of Anniversaries” program, along with Herman Hesse, Claude Debussy and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. This year marks the 200th anniversary of both Jeong’s completion of his seminal work, “Admonitions on Governing the People” (Mongmin simseo), and his release from 18 years in exile and return home to Majae. In April, the city of Namyangju (where Majae is located) and the Korean National Commission for UNESCO held an international symposium in Seoul to commemorate the occasion.

Given that Jeong wrote some 500 books, we would have to consult his works every year to examine the road we are taking today. King Gojong, who struggled to protect the country against external powers in the latter half of the 19th century, turned to Jeong’s books every time he fell into despair over his dreams of achieving reform and autonomy, lamenting that he had not lived in Jeong’s time.

Semiwon, an ecological garden in Yangpyeong, is a popular summer retreat. It features some 270 species of plants, 70 percent of them aquatic.

Although the intention of this writing is to explore that part of the Han riverside where Jeong was born and raised and spent his final years, and to scan the traces of his life and thoughts piece by piece, it will not paint Jeong as a strict academic. Jeong read the “Thousand Character Classic” at the age of four, wrote poetry at the age of seven, and by the age of ten had produced a collection of his own poems. But aside from his genius, there are some endearing details that make him seem more human. For example, despite catching the attention of King Jeongjo after barely passing the lower-level civil service exams, he failed repeatedly to pass the higher-level exams until the age of 28. As for Jeong himself, he certainly would have disliked being remembered as an uptight, narrow-minded man.

Compared to his contemporaries, Jeong Yak-yong was as much admired in Korea as Johann Gottlieb Fichte in Germany or Voltaire in France. Given that Jeong wrote some 500 books, we would have to consult his works every year to examine the road we are taking today.

Four-Day Escape from the Palace

The spectacular view of Dumulmeori seen from Sujong Temple on Mt. Ungil has attracted poets and artists from long ago. Since it was not far from his birthplace, Jeong Yak-yong often went to the temple as a child to read and write poetry.

Jeong, singled out by King Jeongjo, joined the royal research institute and library called Gyujanggak and filled several important posts thereafter, going on to draft and execute Jeongjo’s reform policies. But there were at least two known instances of neglect of duty; it seems that his quirks in character matched his talent and abilities. On one occasion, claiming that he wanted to visit his father, who was serving as magistrate of Jinju, located far away from the capital, he took a leave of absence without permission. This occurred in his second year as a resident researcher undergoing special training at the royal institute. When the king found out about it, he ordered Jeong to be brought back to court and be given 50 lashes, but rescinded the order soon after and granted him a pardon.

When he was a royal secretary in charge of delivering the king’s orders, Jeong played hooky again. Among his writings, he left the following explanation:

“It was 1797, when I lived at the foot of Mt. Nam in Seoul. Seeing the pomegranate flowers bloom in the clearing drizzle, I thought to myself it was the perfect time for fishing at Chocheon. The rules state that a court official can only leave the capital after applying for permission. But as it was impossible for me to gain official permission for a vacation, I simply left and headed to Chocheon. The next day, I cast a net in the river and started fishing and ended up catching 50 fish, big and small. The little boat was unable to sustain the weight of the catch and only a few inches remained above water. I moved to another boat and docked at Namjaju, where we happily feasted on the fish.”

Chocheon was a little stream surrounded by reeds in the village where Jeong grew up. For him it was a symbol of home. Namjaju is a small sandy islet just below Dumulmeori, but Jeong’s adventure did not stop there. Having eaten the fish, he craved some greens. Urging on his friends, he headed across the river for Cheonjinam in Gwangju. That is where Jeong and his brothers had studied Catholicism and, no matter how close the boat was moored, the hermitage was so deep in the mountains that the party had to walk a further 10 kilometers.

“We four brothers went to Cheonjinam with a number of other relatives. As soon as we entered the mountains, the flora was lush and green, the flowers in full bloom everywhere, their scent tickling my nose. All sorts of birds sang and chirped, the sound clean and beautiful. When we heard the birds sing we stopped and turned around, enjoying it all. We reached the temple and spent our time drinking and reciting poetry, not returning until four days later. I wrote 20 poems at the time, and we ate as many as 56 kinds of wild mountain greens including shepherd’s purse, bracken and angelica.” (From “Dasan’s Collection of Poetry and Prose” [Dasan simunjip], Vol. 14)

It is not known whether this particular absence from work was reported to the king.

During the Joseon period, aside from their formal names many people carried ho, meaning “pen name,” or “style name,” used by their friends and close acquaintances. Generally, the pen name reflected an individual’s personality or special traits. Often, houses were also given special names and sometimes people used it for their pen name. When Dasan returned to his home village after retiring from government service, he named his study Yeoyudang (House of Hesitation).

The inner yard of Yeoyudang, the house where Jeong Yak-yong was born and raised, and where he spent his final years. Restored to its original appearance in 1957, the house is part of the Dasan Heritage Site. The name of the house reflects Laozi’s advice to deal with all things carefully with fear in the heart.

Like Crossing a Stream in Winter

“I know my own weaknesses well. I have courage but not the ingenuity to carry things out. I like to do good things but do not have the insight to prioritize and select. So, unfortunately, my endless pursuit of good works has only brought abundant reproach. The Laozi (a.k.a. Tao Te Ching) says that in taking part in favored works, one has to be ‘hesitant, like those crossing an ice-covered river’ and in doing the things one has to do, ‘irresolute, like those who are afraid of all around them.’ This is regrettably so. But these two lines provide a treatment for my weak points!”

Being a young official favored by a reform-minded king made it impossible to avoid having political enemies. Jeong’s acceptance of Seohak, or Western Learning, and Catholicism meant that even the king’s favor could not shield him. In the first month of 1800, Jeong retired and returned to his hometown, where he acquired a small fishing boat with a cabin. He wanted to live with his family on the boat, fishing at Chocheon, and even prepared a name board for the boat, expressing these wishes. But the name board was never hung. The oppression of the Catholic Church, which began in the wake of King Jeongjo’s sudden death in the summer that year, nearly claimed the lives of Jeong Yak-yong and his second-oldest brother, Jeong Yak-jeon; they were both banished to remote places. Jeong Yak-jong, his third-oldest brother who firmly adhered to his faith, was martyred.

Aside from “Dasan,” Jeong Yak-yong had another pen name, “Sammi,” which means “three eyebrows,” from which “Sammijip,” the title of his childhood poetry collection was derived. Childhood smallpox had left a scar on his forehead that made him look as if he had three eyebrows. Jeong bore nine children, but smallpox and measles claimed the lives of six of them. He heard of the death of his youngest son while in exile. “It would be better for me to die than to live but I am still alive; it would be better for you to live than to die but you have already died,” he wrote, expressing his deep sadness.

As a matter of fact, Jeong left moving writings behind, mourning each of his lost children. Except for his eldest daughter, who died four days after birth, they were all buried in the family graveyard on the mountain at the back of his home village. Motivated by this personal grief, Jeong delved into treatments of infectious diseases and wrote two medical books, one on treating measles and the other on preventing smallpox.

Passing Summer by the Han River

After 18 years of exile in Gangjin, Jeong Yak-yong, as if in compensation for that time, lived another 18 years in his hometown. Although he had been born by the riverside and dreamed of a peaceful life in the countryside, reality did not allow for this. In 1819, the year after he returned from exile, he visited the fields at Munam (in Seojong-myeon, Yangpyeong County today). Every autumn he had spent many days there, tending the crops with his brother Yak-jeon, when they went by boat to pay respects at their father’s graveside in Chungju. “It was 40 years ago that I began to dream of living here tilling the fields,” he recalled. Yak-jeon had passed away three years earlier, never returning from exile on Heuksan Island.

Jeong Yak-yong spent the last years of his life editing and proofreading the books he had written while in exile. Even then, his extraordinary abilities and quirky nature did not disappear entirely. He composed 16 poems about ways to beat the heat, some of which were titled: “Playing baduk (go) on a cool bamboo mat,” “Listening to the cicadas in the eastern woods,” “Dangling the feet in water under the moonlight,” “Trimming the branches of trees in front of the house for wind to pass through,” “Clearing the ditch for water to flow,” “Raising the grape vines up to the eaves,” “Drying books under the sun with children,” and “Cooking spicy fish stew in a deep pan.” Did he have a physical constitution that made him feel the heat more than others? Or was he stout?

The Dasan Heritage Site, located at Jeong’s hometown in Namyangju, is a complex that contains his gravesite, his restored birthplace, the Dasan Memorial Hall, and the Dasan Cultural Center. The hundreds of books he wrote during his exile are on display at the Dasan Cultural Center. Korea’s first crane, called geojunggi, which was used to construct the Hwaseong Fortress in Suwon, and many other items related to the versatile thinker, author and public administrator are exhibited at the Dasan Memorial Hall.