The DMZ (Demilitarized Zone) is a military buffer area that stretchesacross the middle of the Korean Peninsula along the MilitaryDemarcation Line, separating North and South Korea. Contrary toits name, this Cold War remnant is the most heavily fortified borderin the world today.

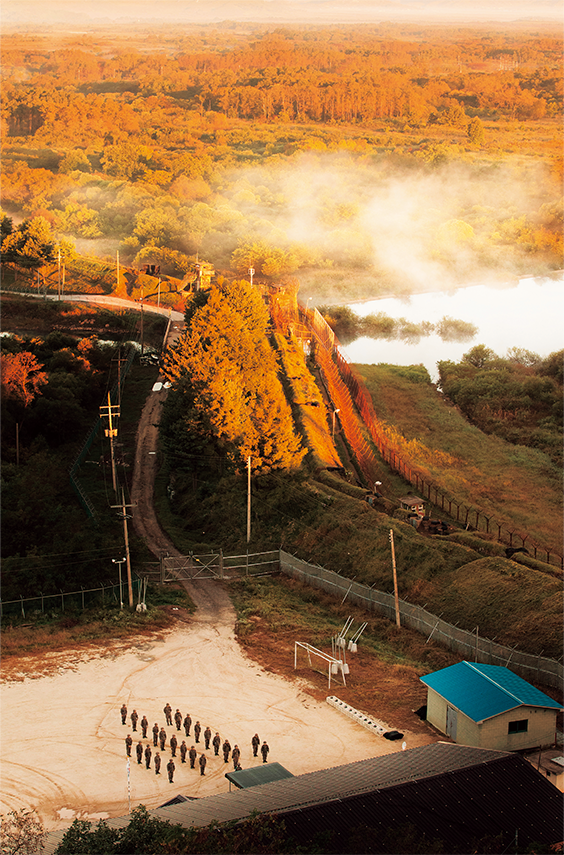

The early morning mist rising from the ImjinRiver hovers over the midwestern front inGyeonggi Province. A military jeep patrols thearea around the barbed wire fence markingthe southern limit line of the DemilitarizedZone, still shrouded in darkness.

At 10:12 a.m. on July 27, 1953, at Panmunjom, LieutenantGeneral William K. Harrison, representing the UnitedNations Command Delegation, and General Nam Il of theDemocratic People’s Republic of Korea signed the Armistice Agreement.Then, without saying a word or exchanging a ceremonialhandshake, they left through separate doors. The DMZ that dividesthe two Koreas was born on that fateful day, the love child of animosityand distrust, silencing gunfire 12 hours later.

Neither War, Nor Peace

This year marks the 63rd anniversary of the DMZ, which wasborn as a consequence of the Korean War. If it were a person, theDMZ would be entering advanced middle age, with more years livedthan left to live. Maybe that’s why people tend to adopt a more tolerantattitude toward the DMZ these days. For example, they oftenconjure up the image of a pristine natural environment long leftuntouched by humans, where wild animals frolic.

But the DMZ is by no means a “frail elderly person” or an “ecologicalhaven.” Rugged plains scorched by repeated wildfires;barbed wire fences running through the green mountains; trenchesand cement stairs meandering up to the ridges; steep and narrowmilitary roads; corn fields tilled by North Korean troops on themountain slopes; bunkers where North Korean troops hide withtheir eyes fixed on the South; and South Korean soldiers keepinground-the-clock watch from frontline guard posts — it might not bea battlefield, but it would be a gross mistake to believe that peaceexists there.

Two soldiers look downover the DMZ from a guardpost at the central front.

DMZ: Reality and Fantasy

The Armistice Agreement stipulates that the DMZ is an area ofland two kilometers wide north and south of the Military DemarcationLine, which extends from the mouth of the Imjin River on thewest coast, marked by the No. 0001 sign post, to Myeongho-ri onthe east coast, marked by the No. 1292 sign post. It is a strip of landcutting across the waist of the Korean Peninsula.

“Along the 155-mile-long barbed wire fence of the truce line”— this is a commonwhen talking about the division ofKorea. To check, a geographer measured the distance along thesouthern limit line, from the mouth of the Imjin River on the westernend to Chogu village on the eastern end. The exact distancewas 148 miles (238 kilometers). Furthermore, technically speaking,the ceasefire line is just a line on the map demarcating the borderbetween the two Koreas. From a historical point of view, it delineatesthe battle lines on that fateful day, which have since been frozenin time.

Soldiers stationed at a centralfrontline unit along theDMZ line up for morningroll call.

When looking out the large glass windows at the observatoriesbuilt along the barbed wire fences, tourists visiting the DMZ areimpressed by the serene green fields in summer and pristine snowland in winter, giving them the illusionthat it is devoid of any activity. Butin fact, cunning tactics are constantlybeing deployed in the border zone byboth sides. For instance, each yearfrom mid-February to May, South andNorth Korean troops conduct operations to burn down the plants and trees that obstruct their field ofvision and line of fire.

The provisions of the Armistice Agreement, which prohibit bothKoreas from crossing the respective limit lines, have been frequentlyviolated since long ago. Each side has been advancing beyond thedesignated limits, moving their barbed wire fences forward bit bybit. There have been many incidents and clashes in the DMZ, suchas those involving forest fires and landmines, digging of infiltrationtunnels, and more recently the resumption of loudspeaker propagandabroadcasts.

The official population around this “no man’s land” is anothermatter of intrigue; it is much less than the actual number of residents.Troops stationed in the area are part of a “hidden population.”For example, the population of Hwacheon County in GangwonProvince bordering the DMZ is said to be around 27,000 as of 2015.But it is no secret that there are many more “invisible inhabitants.”

The DMZ Ecology: Another Myth

The natural environment in the DMZ, contrary to popular belief,is far from natural. The forests have been ravaged by fires, and cutdown and contaminated by the large number of “residents.” Forsome time, scholars have been pointing out that the density of livingtrees in the border area has fallen to less than half the averagein South Korea, urging immediate action to restore the damagednatural ecosystem. Animals living in the barren land have to enduredeafening blasts from the loudspeakers and the glare of floodlightsat night. Not a few fall victim to the ubiquitous landmines.

But reportages on the DMZ often portray the border zone as ahaven for wild animals — herds of roe deer frolicking in the fields,a goat poised high up on a rock staring into the distance, or a familyof wild boars roaming around the barracks. But none of the animalsare posing for the camera. In fact, the cameras are exposing littlemore than the secret habitats of these wild animals.

Although hard to tell from this photograph, a South Korean guardpost at the central front is only a very short distance away from theNorth Korean guard post.

Kim Yeong-beom and Kim Sun-hui were both born in a village insidethe civilian control zone in Cheorwon County, Gangwon Province.In the 1980s, they opened the Frontline Rest Stop in the dandelionfield in front of their village. Longing for the day the two Koreas arereunited, they welcome guests who have gone through a series ofmilitary checkpoints just to get a taste of their spicy catfish stew.

AWAITING THE DAY THE MT. KUMGANG TRAIN RUNS AGAINThe dandelion field in Gimhwa, Cheorwon County, Gangwon Provinceis the northernmost land in South Korea, an unsettling placeover which the black mountains of North Korea loom. The DMZ passesthrough this field. There is also a rusty railroad bridge there. It waspart of the electric railroad to Mt. Kumgang (Geumgang) that waslaunched in 1926 and operated between the Cheorwon and Naekumgang(Inner Kumgang) stations until the line was severed by territorialdivision. The writing on the bridge piers says, “Railroad Disconnected!Mt. Kumgang 90km,” declaring the end of the journey.

In the early 1970s, a young farmer named Kim Yeong-beom, wholived in a village within the civilian control zone in this mountainousarea, proposed to a young woman named Kim Sun-hui from thesame village, quoting the lyrics of the Korean pop song “With You,”which was a big hit at that time: “Will you not spend the rest of yourlife with me in a picturesque house I’ll build in the dandelion field?”Azaleas happened to be in full bloom by the Hantan River. She noddedin acceptance.

Ten years after they were married, while living happily with a sonand a daughter, Kim was finally able to keep his promise. He hadbeen pleading with the county office and military units based in thearea, and at long last gained approval to build a house in the dandelionfield. He put up the sign “Frontline Rest Stop” in the hopes thatsome day the railway would be reconnected, bringing trains filledwith tourists. Although Mt. Kumgang tourists are not likely to stopby anytime soon, word has spread that his wife cooks a mean spicycatfish stew. People are also intrigued by the couple’s heartwarminglove story, making this place a hidden attraction inside the civiliancontrol zone.

Jeongyeon Railroad Bridge, part of the Mt. Kumgang Line, was builtover the Hantan River in Cheorwon County in 1926. The sign on thebridge reads, “Railroad Disconnected! Mt. Kumgang 90km.”

When looking out the large glass windows at the observatories built along the barbed wire fences,tourists visiting the DMZ are impressed by the serene green fields in summer and pristine snow land inwinter, giving them the illusion that it is devoid of any activity. But in fact, cunning tactics are constantlybeing deployed in the border zone by both sides.

Five Faces of the DMZ

It is time to move beyond the common perception of the DMZ asa “land of peace and life,” or the “tragic wound of a divided nation,”and take a clearer look at its true face.

First, the DMZ is a living war museum. The Korean War, whichbroke out on June 25, 1950, was a de facto world war in which some60 countries, including 10 communist nations, took part directly orindirectly. No war in the history of mankind has involved as manynations and diverse nationalities in a single place. The DMZ is evidenceof the East-West power struggle and in itself a Cold War ary.

Second, the DMZ is a rich repository of anthropological and historicalresources. In 1978, Greg Bowen, an American soldier stationedin Korea, found an Acheulean hand-axe by the Hantan Riverin Yeoncheon County, Gyeonggi Province. This is evidence that some300,000 years ago, a human species older than modern humanslived in this area. Ancient mountain fortresses along the Hantanand Imjin rivers reveal that the ancient Three Kingdoms — Goguryeo,Baekje and Silla — frequently engaged in armed hostilitiesin this region some 2,000 years ago. In 901, during the Later ThreeKingdoms Period, Taebong was founded at a site near today’s Cheorwon,in the middle of the DMZ. In 918, the Goryeo Dynasty wasestablished at the same location, and in 1392, the Joseon Dynastywas founded in the Goryeo capital, Gaeseong (also Kaesong), justnorth of the DMZ. As such, the DMZ was the birthplace of threeKorean states.

South and North Korean soldiersstand facing each otheron either side of the MilitaryDemarcation Line which runsthrough the Joint SecurityArea in the truce village ofPanmunjom. The building onthe opposite side is Panmungakof North Korea, and theblue building on lefthand sideis a JSA conference room.

Third, the DMZ is a treasure trove of modern cultural heritage.The old ruined city of Cheorwon was home to a population of some37,000 during the 1940s. It was originally a planned city built by theJapanese during its colonial rule, but was destroyed in bombingraids during the Korean War. Ruins of buildings that still remain —the county office, police station, primary school, church, the agriculturalproducts inspection center,icehouse, train station, and the CheorwonCounty headquarters of the NorthKorean Workers’ Party — are the silentremnants of a city that once was. Cheorwonwas part of North Korean territoryfrom 1945, just after Korea’s liberationfrom Japanese rule, until thesigning of the Armistice Agreement in1953. Seungil Bridge, which crossesthe Hantan River, was built by North Korea in 1948. Next to this isthe Hantan Bridge constructed by South Korea in 1996.

Fourth, the DMZ is a melting pot. Right after the ceasefire, thecivilian control zone outside the DMZ encompassed 100 or so emptyvillages. The government implemented migration measures toattract settlers into the area. As a result, in 1983, when the areadelineated by the civilian control line was at its largest, a total of39,725 residents in 8,799 households were living in the 81 villageslocated within the civilian control zone. Subsequently, as the civiliancontrol line was moved further north, many of these villages wereexcluded. The people who settled in the villages d a uniqueculture. The mish-mash of the disparate cultures of people with differentdialects, ethos, customs, and family histories, melded with themilitary environment to shape a distinct culture of “the third zone.”

Lastly, the natural ecosystem of the Cold War era has beenlargely preserved in the DMZ. Proper ecological succession wouldnot have been possible during the Cold War due to excessive interventions.Even so, pools of water where artillery shells fell havesince turned into ponds, and abandoned rice paddies have becomeswamps. Water plants in these swamps have become home to roedeer while insects and earthworms attract wild animals and birds.

The trees standing in the fields where South and North Koreansoldiers engage in an ancient military tactic of fire warfare every yearhave stopped growing side branches.Perhaps they have learnedthat it is best to concentrate on growing upward so that the flamescan pass beneath their branches. After the fires have swept through,the fields turn green again in spring since only the young foliage isburned away. But large animals, like wild boars, will find little to eatin these fields. Some animals survive on the soldiers’ leftover food,but many are injured or killed by landmines and booby traps.

The border zone is also exposed to latent viruses and pathogens.Hantavirus hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, which is knownto have afflicted about 3,000 UN troops during the Korean War, stillexists there. And diseases like rabies and malaria are rampant inthe area.

Sustaining Dreams of Unification

These faces of the DMZ constitute a historical and cultural heritagenot found anywhere else in the world. This is an invaluablelegacy that has been passed on by the 20th century to the Koreanpeople today. It is now up to us to use this unique heritage to bringcloser to reality our dreams of reunification.