© Gian

The entrance is narrow and the hallway is long. Light seeping from the darkness is constant with unwavering intensity. The pace of time slows. From the left wall, a misty light introduces itself. Something lies there, supine; something vast and firm, a great stone or block of ice. It gradually loses any discernible form, turning into water which slowly vaporizes. The ascending mist transforms into another world. But it is short-lived; eventually a stone reappears. Making our waypast video art by Jean-Julien Pous, we are christened by his vision of the “Cycle” of the universe.

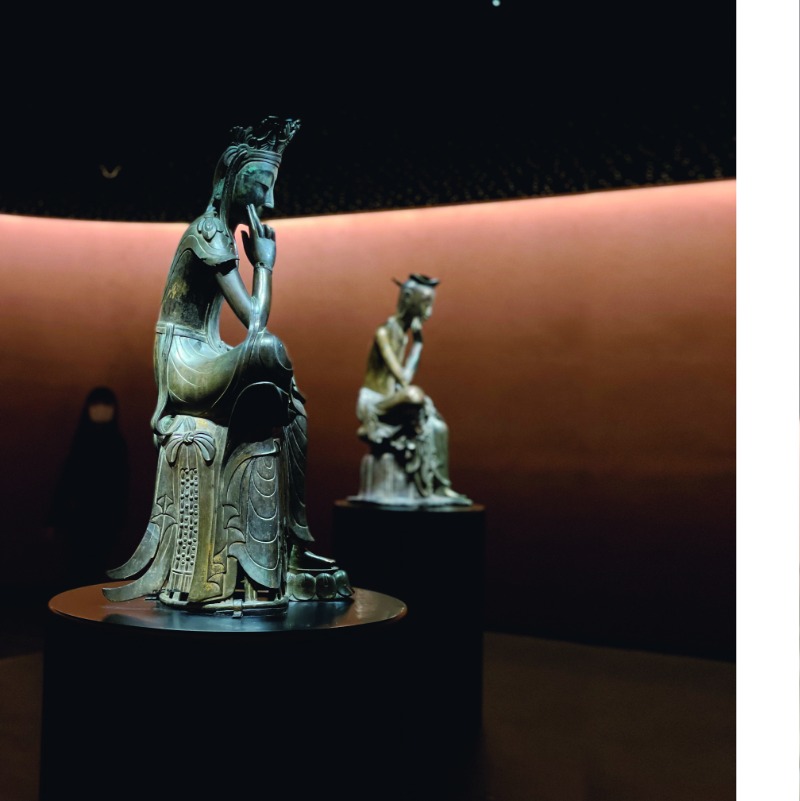

Finally, the “Room of Quiet Contemplation” is before us. Our five senses awaken. Every pore of our body opens and our inner space expands – infinite. As consciousness and calm become one, the floor inclines upwards, little by little, barely noticeable, leading to where light and darkness intersect around two mystical beings.

This room, opened in November 2021, is a collaboration between architect Choi Wook and a team of “brand story” experts commissioned by the National Museum of Korea. Most people first associate the Louvre in Paris with the Mona Lisa. In much the same way, visitors to the National Museum of Korea are now sure to think first of the Room of Quiet Contemplation and its bodhisattva statues, which have rarely been displayed together.

A full millennium separates the Mona Lisa and the two sculptures. Leonardo da Vinci painted the portrait, measuring 77 × 53 cm, in the early 16th century. The sculptures, less than a meter tall, were made in the late 6th and the early 7th centuries. They represent the height of Buddhist art from the Silla period and are designated Korea’s National Treasures No. 78 and No. 83.

These masterpieces share two similarities that define them. First, unlike other seated, standing, or reclining Buddhist images, they hover somewhere between sitting and standing, draped over a small round stool, right foot perched on left knee. Meanwhile, their right hands are raised, the tips of their index and middle fingers grazing their chins, showing an attitude of deep thought.

What are the Maitreya Bodhisattvas supposed to be thinking? We can only speculate, just as we do with “The Thinker,” Auguste Rodin’s iconic sculpture unveiled some 1,300 years later.

Buddhists assume these figures to be contemplating the four phases of life: birth, old age, sickness and death. Yet, encountered in a museum after enough time has passed, even Buddhist images can break free of religious connotations. True contemplation calls for surrendering and finding oneself simultaneously. Perhaps the subtle smiles of these two pensive bodhisattvas are a nod to the faint vibration that lives between this very surrender and discovery, an internalization of time and space that is both broad and deep.