Yeongju is steeped in history and legend. Despite its moderate size, the mountainous town encompasses the sources of two large rivers and the birthplaces of many famous historical figures. It is also home to a storied log bridge, a mysterious “floating rock” and two UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Museom Village in Yeongju, North Gyeongsang Province lies at the intersection of two streams that flow down Mt. Taebaek and join the Nakdong River. Before a modern bridge was built in 1979, this single log bridge was the only passage to the outside world from the village, which is surrounded by waterways on three sides and mountains at the back.

When I opened my map, I imagined what residents of Yeongju centuries ago might have believed: that the world ended where they lived. The small city sits at the top rim of North Gyeongsang Province, which occupies the southeastern part of the Korean Peninsula. The northern edge of Yeongju abuts Gangwon Province, where Mt. Taebaek stands tall, and its western side shares a long border with North Chungcheong Province, where the high peaks of Mt. Sobaek are clearly visible.

On the city’s south side, a steady stream of arrivals once came ashore, laden with tales of distant places. I thought about the waterway that carried them northward to Yeongju – the Nakdong River, the longest river in South Korea.

The geography section of the “Annals of King Sejong” from 1454 says, “The sources of the Nakdong River are Hwangji on Mt. Taebaek, Chojeom in Mungyeong County and Mt. Sobaek in Sunheung. The waters join and when they reach Sangju, they form the Nakdong River.” Sunheung was the former name of the Yeongju area. Moreover, Yeongju was the wellspring of several small tributaries of the Han River, which flows east to west and bisects Seoul. As the source of two of the most important rivers in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula, Yeongju in pre-modern days was, in effect, the beginning and end of the world to Koreans.

A mountainous town with a population of 108,000, Yeongju is a two-hour drive from Seoul. The last stage of the trip includes the Jungnyeong (Bamboo Pass) Tunnel, a 4.6 km passageway through Mt. Sobaek, connecting North Chungcheong Province with North Gyeongsang Province.

Museom Village was formed around the mid-17th century as its fertile land attracted inhabitants. It now has some 40 old traditional houses and 100 residents. It is a clan community, most of its residents belonging to two clans, the Kims hailing from Yean and the Parks from Bannam.

CROOKED BRIDGE

I headed for Museom Village in the southern part of Yeongju. Water flowing from two streams – Yeongjucheon and Naeseongcheon – merge and surround the village on three sides, making it look like an island. Museom means “an island floating on water.” The village, established in the mid-17th century, is filled with hanok, or traditional Korean houses, which were once occupied by local elite families. In terms of geomancy (pungsu in Korean, feng shui in Chinese), the topography here supposedly emits high energy, blessing its residents to achieve their goals. This belief probably arose from the broad, fertile fields which ensured self-reliance.

Among the village’s old traditional houses are 16 well-preserved examples of typical late Joseon Dynasty homes. The village is not widely known to the general public, so it still maintains the quiet atmosphere of a traditional scholarly village.

In modern times, the village came to be known for a single log bridge, laid across the stream to serve as the only passage to the outside world. Indeed, it did until the Sudo Bridge opened in 1979.

In the past, the monsoon season stirred up the stream enough to destroy the bridge regularly, so it had to be rebuilt many times. Today, the log bridge stretches some 150 meters, but instead of being straight across, it is shaped in an enigmatic big S. The beautiful and narrow span is loved by people of all ages and has appeared in television drama series, including “The Tale of Nokdu” (2019), “My Country” (2019) and “100 Days My Prince” (2018). Not surprisingly, walking across the bridge is on the checklist of an endless stream of visitors, myself included.

Up until the end of the 19th century, Museom had some 500 residents in 120 households. The village produced numerous academics and Confucian scholars as well as five independence fighters who made significant contributions to the nation’s liberation from Japanese rule in the 20th century.

Dirt paths along stone walls lead to the Museom Village Exhibition Hall. In one corner of the yard is a monument to the poet Cho Chi-hun (1920-1968). There is no Korean student who has not recited Cho’s poem, “The Nun’s Dance” (Seungmu), from their textbooks. Museom was the hometown of Cho’s calligrapher wife, Kim Nan-hee (1922-); he left his poem, “Parting” (Byeolli), engraved here on a large rock in her handwriting. The poem is about a shy, new bride tearfully watching her husband leave for a long trip, from behind a big pillar in their home. I tried to imagine the young husband in the poem crossing the log bridge one precise step at a time. Suddenly, I felt I could explain why the bridge had an S-shape. It forced a slow pace, prolonging sad farewells.

DYNASTY BUILDER

Not far from the city center is the childhood home of Jeong Do-jeon (1342-1398), a scholar-official who was credited with laying the cornerstone of the Joseon Dynasty by establishing its ruling ideology and system of government. Jeong’s home came to be called the Old House of Three Ministers (Sampanseo Gotaek) because the family produced three government ministers (panseo) during the Joseon period. Though the house has been relocated from its original site due to flooding, it still emanates an aura of power from an influential family.

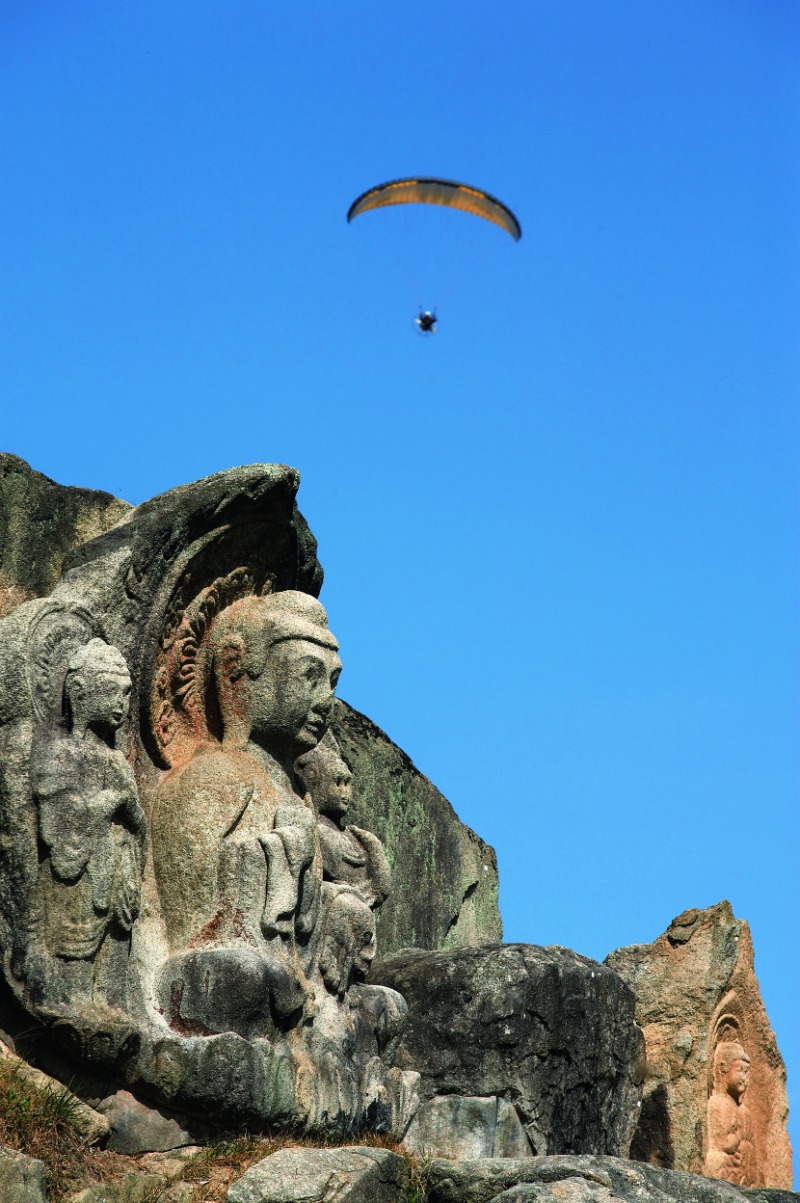

The Rock-carved Buddha Triad on a high streamside cliff overlooking Seocheon exemplifies the sculptural style of the Unified Silla period (676-935). These Buddhist images had been severely vandalized by the time they were discovered, but they still emanate a strong spirit.

In the city center, I looked around Yeongju Modern History and Culture Street, then walked up a gentle slope and arrived at Sungeunjeon (Hall of Worshipping Grace). This is a shrine for the portrait and spirit tablet of King Gyeongsun (r. 927-935), the last ruler of Silla. It is said that the king stopped at Yeongju on his way to Kaesong to surrender to Goryeo. Having just met a revolutionary thinker who opened the doors for one dynasty, I now encountered a tragic king from another, who had to offer his country to a rising monarchy to spare the lives of his subjects.

Today, Yeongju commemorates the king’s love for his people and honors him as a deity. Early morning the next day, I tackled the long, uphill path and steep 108 steps to Buseok Temple, or the Floating Rock Temple. The temple is listed as UNESCO World Heritage along with six other historic temples, including Tongdo Temple in Yangsan, Bongjeong Temple in Andong, Beopju Temple in Boeun and Seonam Temple in Seungju, under the name “Sansa, Buddhist Mountain Monasteries in Korea.” Buseok Temple is especially popular in the autumn, when leaves change color to turn the area into a gorgeous tapestry where sought-after apples are dispensed, pairing with Yeongju’s well-known beef and ginseng.

The legendary rock is found beside the temple’s main hall, named Muryangsujeon, or the Hall of Infinite Life. Legend has it that the rock was used by a guardian dragon to float above followers of different beliefs and scare them from attempting to interfere with the temple’s construction. Buseok Temple was built in 676 during the golden era of Silla, when it defeated rival states Goguryeo and Baekje and successfully unified the Three Kingdoms. At the time, Buddhism received widespread support as the state religion, as evidenced by the scale and importance of Buseok Temple. But 250 years later, Silla would give way to a new dynasty. When I finally arrived in front of the Hall of Infinite Life, one of the oldest wooden structures in Korea, thoughts of the rise and fall of dynasties vanished. I faced the beautiful hall, where Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Pure Land, resides. Indeed, there on the left was the famous buseok, the floating rock.

“Treatise on Choosing Settlements” (Taengniji), an 18th-century ecological guide, says that a rope can pass cleanly underneath the rock. The scientific explanation is that the rock fell away from the granite behind the temple and landed on smaller stones. The fallen rock does not appear to be floating, nor does it touch the ground. To me, the rock looked like a large table that could seat some 20 adults.

The bell pavilion of Buseok Temple offers a panoramic view of the temple grounds and the Sobaek Mountain Range in the distance. The temple was built shortly after Silla unified the Three Kingdoms in 676.

In 2018, it was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List along with six other Buddhist mountain monasteries across Korea.

Buseok Temple has two famous pavilions, Anyangnu (Pavilion of Tranquil Nourishment) and Beomjongnu (Bell Pavilion), located on the central axis of the temple compound leading up to the main hall. The Bell Pavilion’s bronze bell, wooden fish, cloudshaped metal plate and drum are struck twice a day.

REPEATING CYCLE

In the afternoon, I crossed Maguryeong (Horse and Foal Pass), a hill in the direction of Gangwon Province, and visited the mountain village of Namdae-ri, where the tragic boy king, Danjong (r. 1452-1455), stayed on his way to exile after being deposed by his uncle, King Sejo (r. 1455-1468). This is where the southeastern source of the Han River is located.

The trail around Sosu Seowon has hundreds of red pine trees, ranging from 300 to 1,000 years old. Founded in 1542, Sosu Seowon was Korea’s first private Confucian academy. It was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2019, along with eight other Confucian academies across Korea.

At Seonghyeol Temple, a quiet Buddhist temple secluded in the mountains, there is a beautiful ancient building named Nahanjeon, or the “Hall of the Arhats.”

Its doors feature exquisite carvings of lotus flowers and petals, cranes, frogs and fish.

Later, I returned to the neighborhood beneath Buseok Temple and visited Sosu Seowon, one of the nine private Confucian academies of the Joseon Dynasty that are on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Sosu Seowon, also known as Sosu Academy, was the first Confucian academy that received a royal charter. It houses the spirit tablets of some of the country’s greatest Confucian scholars, including An Hyang (1243-1306), who first spread Neo-Confucianism on the Korean Peninsula.

The more I looked around Yeongju, the more I admired its uniqueness. It was home to the man who laid the foundations of a new dynasty and a place that revered the last ruler of a disappearing kingdom; it cultivated numerous scholars and politicians at its prestigious Confucian academy and is where the traces of a young king who was banished and killed in a power struggle can still be found. I felt like I was watching one huge cycle repeating itself.

The writings of another famous son of Yeongju, the scholar and patriot Song Sang-do (1871-1946), prompted me to think deeply about origin and return. His book, “Essays of Song Sang-do” (Giryeo supil), published in 1955, describes in remarkable detail the life of Koreans under Japanese colonial rule. Giryeo was Song’s pen name. Every spring, beginning in 1910, the year Japan colonized Korea, Song left on long journeys around the country to meet bereaved families of patriots and collect newspaper reports and other records about related incidents. He risked death if found with those materials, so he twisted his notes and clippings into the ropes that he used as backpack straps. Late in the year Song would return, worn out and haggard. To be the origin of everything and, at the same time, the “other shore,” or the entrance to nirvana, to which all things can return – this is the spirit entrenched in Yeongju.

On my last morning in Yeongju, as I prepared to return to Seoul, I was still thinking about Song. I decided to take the old road over Jungnyeong. As I drove on the steep, narrow and winding mountain road, I wanted to feel the immense and resolute spirit of the scholar who would have left Yeongju and crossed the rugged passageway on foot. When I reached the top of the ridge, I asked myself whether I was returning to Seoul or leaving Yeongju. I was sure I would be back again, so I decided to tell myself that I was just starting out.