It is characteristic of Korean wooden furniture to bring out the natural beauty of wood by emphasizing its grain rather than relying on elaborate coloring or intricate carving. Park Myung-bae, a titleholder of National Intangible Cultural Heritage in joinery (

somokjang), complements traditional woodworking techniques with a meticulous design process to achieve aesthetic proportionality.

Master Artisan Park Myung-bae at his workshop in Yongin, Gyeonggi Province. Meticulously crafted through a rigorous drafting process and characterized by its simple elegance, Park’s work embodies the distinctive characteristics of traditional wooden furniture.

Crafts that involve working with wood are broadly divided into carpentry, which focuses on building wooden structures (daemok), and woodworking (mokgong), which involves crafting furniture, carving artifacts, and creating precise joints (somok). Artisans who use traditional joinery techniques to make furniture, such as cabinets, desks, stationary chests, and wardrobes, are called somokjang. While wooden artifacts from the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) display ornate artistry, those from the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), influenced by the values of Confucianism, are characterized by simplicity and understated elegance.

The work of master artisan Park Myung-bae represents the typical characteristics of Joseon-era wooden furniture, but with a more exquisite quality thanks to the materials used for the veneer. With an aesthetically pleasing combination of simple lines and dynamic patterns on its wooden surfaces, Park’s work has received praise for embracing modernity while remaining faithful to tradition.

Park explains his philosophy: “Wood without an elaborate grain is useless to a woodworker. For me, wood grain is more beautiful than anything artificial. It’s so natural that you never get bored looking at it. Since traditional furniture is made with little decoration or carving, it is crucial to bring out the beauty of the natural wood grain.” As a result, the artisan has a deep affection for the intricate patterns found in the wood of old zelkova trees that resemble intertwined dragons (yongmok). To Park, they are as beautiful as an ink wash landscape painting.

Technical Skills and Creativity

National Intangible Cultural Heritage titleholders are artisans who have completed many years of extensive training under a master artisan in their respective fields. They serve apprenticeships—first as successors and then as certified trainees—before becoming instructors for heritage transmission as their careers progress. Park, however, took a different route and honed his skills in an unconventional way, quickly gaining recognition, nonetheless. At the age of 21, he won first prize in the woodworking category at the 1971 National Skills Competition. In 1989, he was awarded the Grand Prize for his wood-grained tray (mongniban) at the Dong-A Handicraft Competition, sponsored by the Dong-A Ilbo newspaper. Three years later, Park’s elegant pine wardrobe won the Presidential Prize at the Traditional Handicraft Art Exhibition hosted by the Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation. He spent nearly a year working on the design for this piece, using a method he developed toa unique color tone by searing the pine wood panels with a hot iron.

A s Park expounds, “Originally, this was a technique used on Korean paulownia wood. When paulownia boards are burned with a hot iron and then rubbed with straw, the softer parts are slightly depressed and blackened while the harder parts remain raised, revealing the distinct grain of the wood. The natural grain is so subtle and graceful that this technique was widely used on the furniture of reception rooms (sarangbang) in traditional Korean houses. I applied it to pine wood to achieve more exquisite patterns, and my experiment was rewarded with this great honor.”

Park’s work is exhibited in various locations around the world. A complete set of his furniture, for instance, is on display at the Korean Gallery of the Ethnological Museum Anima Mundi, part of the Vatican Museums, while his living room furniture can be seen at Korean Cultural Centers in major cities such as Berlin, Los Angeles, Osaka, Warsaw, and Washington, D.C. Park also oversaw the production of over 100 pieces of furniture for the restoration of Seoul’s Unhyeongung, a royal residence and the birthplace of Gojong, Korea’s penultimate monarch who ruled from 1864 to 1907. In addition to Park’s outstanding artistry, his extensive knowledge of traditional woodworking techniques was vital to this colossal project.

In traditional Korean wooden furniture, artisans utilize joinery techniques, connecting wooden components through grooved slots or dovetails, and avoid the use of nails or glues. As a young artisan, Park sought out esteemed woodworkers on his journey toward mastering over 70 methods of joining wood.

A Special Relationship

Park was born in 1950 in Hongseong, South Chungcheong Province. His family was so poor that he had to stop his formal education after elementary school. At the age of 18 he moved to Seoul, on the recommendation of a relative who happened to be a carpenter, and entered the workshop of Choi Hoe-gwon, a professor at the Seorabeol Arts University (now called the Chung-Ang University College of Arts). As a result, Park was first introduced to woodworking as an art form, rather than with the aim of producing furniture commercially. Although Park lacked the tutelage of a master artisan, he would have considered Prof. Choi his teacher.

Park recalls, “In the past, professors and specialists focused on design, while the actual production was done in woodworking shops. By running errands for Prof. Choi’s workshop, I was able to observe the entire process of a project, from planning to completion. I may not have been able to study at university, but I think I learned a lot more from the professor’s workshop.”

Some years later, when the workshop closed after Prof. Choi emigrated to Canada, Park had to reconsider his career path. “I thought modern crafts, with their emphasis on individual artistic style, did not suit me, so I turned to traditional furniture making.”

At this point, he sought out a number of renowned woodworkers in order to learn traditional joinery techniques and began acquiring more than 70 methods of joining wooden parts without the use of nails. These methods are critical within traditional joinery, involving years of drying and treating wood for aeration. In 1980, having mastered all the necessary skills to become a traditional joiner, Park began working on his own at the age of 30.

The Best Blueprint

Shortly after setting up his own workshop, Park happened to meet Choi Soon-woo (1916–1984), then director of the National Museum of Korea, and this encounter marked a turning point in his career. As one of the founders of the field of Korean art history, Choi became Park’s mentor, imparting to him his philosophy and insights regarding traditional crafts.

Choi helped Park gain an appreciation of the proportionality of traditional Korean furniture: the front is divided into frames and given panels of high-quality wood with an attractive grain structure. In a country with four distinct seasons such as Korea, where temperature and humidity fluctuate greatly throughout the year, furniture should be constructed with multiple sections, since the use of solid wood panels can lead to warping. While these sections are included for functional reasons, they alsoa sense of aesthetic proportion. Thus, the question of how to divide them in order to optimize this proportionality becomes a crucial concern in designing a piece of furniture.

In 1984, Park was commissioned to decorate the main room in the inner quarters of Cheongwadae, then used as the presidential residence. Throughout the entire process, he learned a great deal from Choi, including selecting the right type of wood, designing with attention to proportion and form, and actually producing the finished items. Just as the nobility of the Joseon Dynasty commissioned skilled woodworkers and worked with them to design and produce custom furniture for their homes, the artisan worked with the museum director to revive the original forms of Joseon-era furniture. Although this partnership was cut short by Choi’s untimely death, Park still adheres to the practice of creating detailed blueprints for each piece of furniture he builds, just as he did when working with his former mentor.

Park explains, “After drawing a blueprint in full scale and hanging it on the wall, I study it for a long time. That’s how I notice things today that I didn’t see yesterday, or something that previously looked okay but might need to be modified. Over time, I revise and redraw things repeatedly in order to develop the best design.”

Park’s rigorous design process has earned his furniture wide acclaim for its meticulous proportions and warp-free quality. Committed to recreation rather than replication, Park continues to sketch and design new pieces whenever he finds the time. Over the years, he has taught 19 certified trainees, including his two daughters, along with numerous other students. He has also maintained a steadfast dedication to the annual exhibition The Master Joiner Park Myung-bae and His Apprentices, whose 18th edition took place in August. With unwavering ambition, Park continues to explore how to further develop the traditional craft.

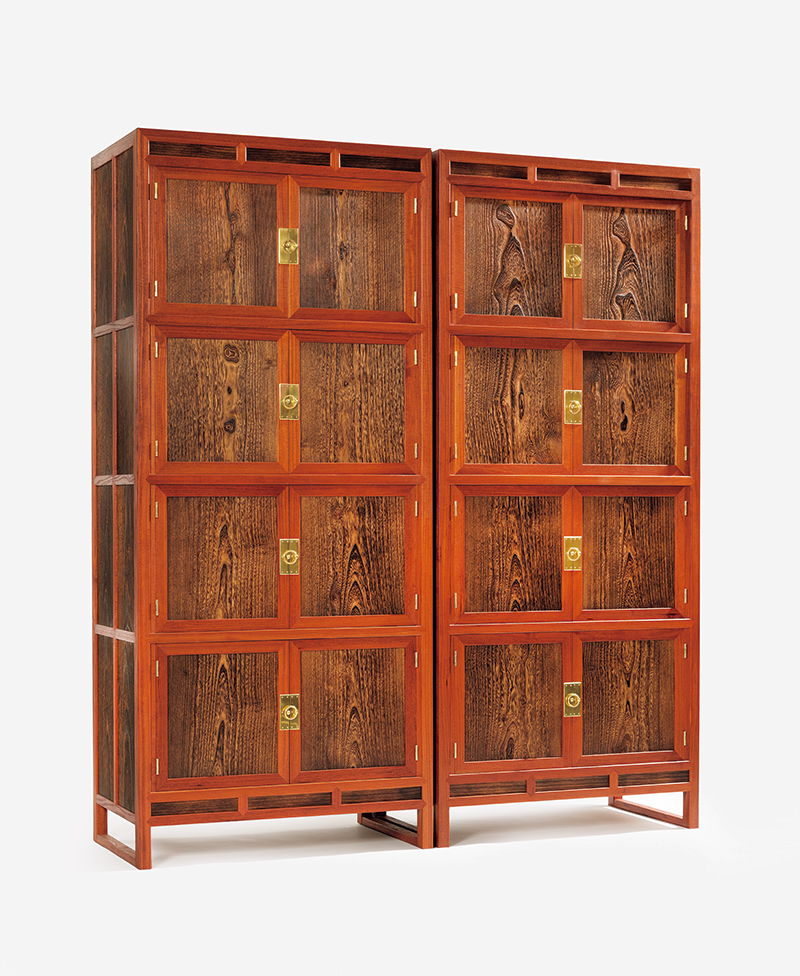

Showcasing simple sections of the façade and rich woodgrain, the four-storied bookcase is distinguished by its refined splendor. In order to protect the wooden boards from potential warping or damage due to repeated contraction and expansion, traditional furniture is crafted with multiple sections. This construction also highlights the inherent beauty of form and proportion.

Known as a meoritjang, this beautifully grained bedside chest is another example of Park’s work. The single chest served as a convenient storage space for items to be kept close at hand. Men used it for storing important s, while women used it for their daily wear.

The drop-front chest, called bandaji in Korean, has a hinged front opening. A necessity found in households of people from every walk of life, the chest exhibits distinct regional characteristics. This photograph shows a bandaji from Ganghwa Island, with a decorative hinge shaped like a gourd bottle.