The performing arts are experiencing a boom in staged readings that convey the literary nature of plays before they become theater productions. They are staking a claim as a genre of their own as they introduce experimental elements, including music and video, and expand the scope of performing arts.

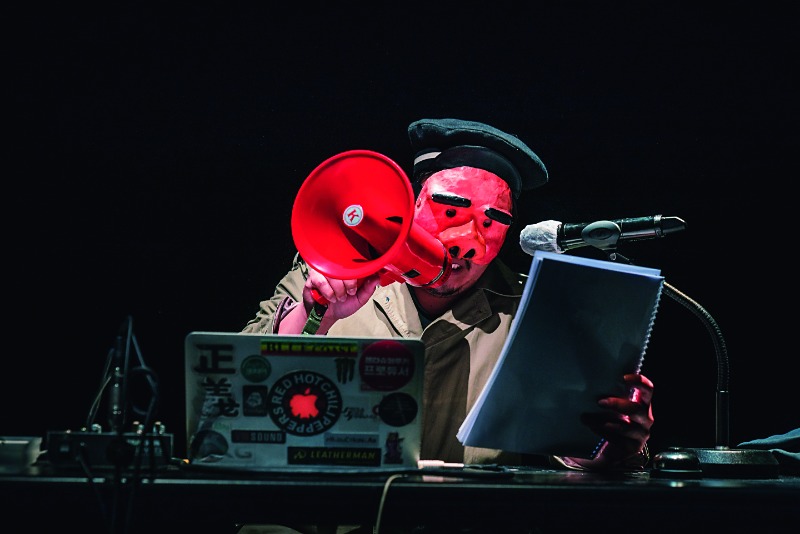

October 2020, actors from Korean theater company Poonggyeong read from “Lobbyist” by Chinese playwright Xu Ying in the third annual “Chinese Play Stage Reading” series, sponsored by the Performing Arts Network of Korea and China.

Courtesy of Performing Arts Network of Korea and China

First popularized in 1945 by a New York theater group called Readers Theatre Inc., staged readings have been gradually gaining traction for decades. The entire focus is the text of a play; actors only read their parts to the audience, the set design is stripped down to a bare minimum or non-existent, and the lighting and wardrobes are simplified as well. Korea can also claim a performance form that could be seen as a kind of proto-staged reading itself. Indeed, the term jeongisu defined someone who read novels aloud as a legitimate profession in the late Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). Known for having superb oral and acting skills, ijeongisu made their living by giving theatrical readings of classic novels. Considering how widespread audiobooks have become in recent years, we could say that the jeongisu were far ahead of their time.

In the modern era, staged readings became a stepping-stone to full theatrical production. They are often used to market the piece to potential sponsors and gauge audience reactions. Around the early 2000s, however, staged readings became performances themselves. The form is now well on its way to becoming an official genre of its own. It is not just professional theater companies, either; staged readings are being performed by community groups and clubs for people who enjoy reading plays, and in schools to develop students’ thinking skills and poetic sensibilities.

International Exchange

Many different institutions and organizations have been instrumental in lifting staged reading to its current popularity. Among them, the Korea-Japan Theatre Exchange Council and the Japan-Korea Theater Communications Center have been pivotal to the effort. For twenty years, the two organizations have facilitated the steady translation of each other’s plays and put on regular performances as well.

Jointly launched by seven theater companies in Japan, the Japan-Korea Theater Communications Center has been bringing contemporary Korean plays to Japanese audiences since 2002, with the support of the Japanese Ministry of Culture. In the first year, readings of works by leading Korean playwrights, including “Finding Love” by Kim Gwang-rim, “Generations Untold” by Park Geun-hyeong, “Empty-handed” by Jang Jin and “Crazy Kiss” by Cho Gwang-hwa, were staged over four days in the basement theater of the University Student Union Building in Tokyo’s Suginami City. The following year, the Korea-Japan Theatre Exchange Council staged readings of three contemporary Japanese plays at the National Theater of Korea’s Byeloreum Studio. Counting the tenth event, staged this past February at the National Theater Company’s Baek Seonghui & Jang Minho Theater, over 50 plays by 50 playwrights have been performed through the two countries’ efforts.

In the beginning, this project shed all theatrical elements, putting the spotlight exclusively on the readings. But certain theatrical expressions have gradually appeared to enhance the writing and style of the plays themselves. This year’s performances showcased elements that were decidedly closer to traditional theater.

In many cases, pieces put on as staged readings go on to become full-fledged theatrical productions. One standout example would be the Japan-Korea Theater Communications Center’s 2019 staged reading of Lee Boram’s “The House Where Boy B Lives,” a play about a 14-year old boy guilty of murder and his family, who are isolated by their community. In 2020, this piece became a full-fledged play, directed by Manabe Takashi. Receiving an award for excellence in the theater category of the Japan Media Arts Festival that year, it also became the first Japanese performance of a Korean play to receive a prestigious award. Meanwhile, in Korea, Japanese plays such as “I Want to See Your Parents’ Faces” by Seigo Hatasawa (about school violence) and “The Great Life Adventure” by Shiro Maeda (a high-spirited depiction of youthful exploits) were also staged to enthusiastic acclaim.

A scene from a staged reading of “Two Stray Dogs” by Chinese playwright Meng Jinghui, in which different human milieus and complex human societies are satirized through a dog’s perspective.

Courtesy of Performing Arts Network of Korea and China

Relatable Stories

The “Chinese Play Staged Reading Performance,” put on by the Performing Arts Network of Korea and China, is also noteworthy. Since 2018, this association has translated and published several Chinese plays each year to promote cultural exchange between Korea, China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. In addition, one of the translations is selected for staged reading. The fifth edition, held this past April at the National Theater Company of Korea’s Myeongdong Theater in Seoul, was so highly anticipated that tickets sold out almost immediately. This suggests that Korean audiences’ interest in Chinese plays has bloomed.

Dozens of traditional and contemporary Chinese plays have been introduced to Korea through these staged readings. Among them, “Fish Man,” “Camel Xiangzi”” and “One Word is Worth Ten Thousand Words” became successful theater productions as well. “Fish Man,” the 1989 debut work of Guo Shixing, one of China’s most influential living playwrights, uses the popular Chinese hobby of fishing to raise questions about our truest attitudes toward life itself. “Camel Xiangzi”,” an adaptation of the eponymous 1937 novel by Lao She, features a rickshaw driver who navigates a turbulent life that reflects the chaotic times around him. It was also published in English under the title “Rickshaw Boy.” On the other hand, “One Word is Worth Ten Thousand Words” is a reinterpretation of the eponymous novel by realist author Liu Zhenyun. Mou Sen, a pioneer in Chinese experimental theater, produced the reinterpretation of the drama set in a rural village.

When the cross-border, collaborative program began, Korean audiences knew practically nothing about Chinese theater, but with each passing year, their interest and excitement rose. The actors’ voices have successfully conveyed the warmth and insight of these works and projected a keen gaze, penetrating the very essence of life.

A scene from a stage reading of “Tea House” at the National Theater Company of Korea’s Myeongdong Art Theater. A story about the tumultuous lives of a group of tea house regulars in Beijing, this production was helmed by star Korean director Koh Sun-woong.

Courtesy of Performing Arts Network of Korea and China

“Home Guest” by playwright Yu Rongjun is a celebrated work that poses witty yet sincere questions about the meaning of life. Held at the Namsam Arts Center in 2020, this production by theater company Juk-Juk successfully conveyed the emotional message of the original work.

Courtesy of Performing Arts Network of Korea and China

New Directions

These days, staged readings are undergoing a transformation. Directors are adding their interpretations and actors are displaying more emotion. Going by the name “dimensional staged readings,” these performances use theatrical elements like music, set design, lighting and costumes. In some cases, they add video or music to enrich the narrative. In short, instead of being focused entirely on delivering the text, dimensional staged readings draw on directors’ visions and adopt certain aspects of traditional theater.

Since last year, the National Theater Company program “Creative Empathy: Plays” has explored new possibilities for Korean theater. To determine the viability of staging selected published works, they first produced a dimensional staged reading. One such performance was “Goldfish Wheelchair,” held in February at The Theater PAN in Yongsan District; it deals with self-awareness and understanding between the perpetrator and victim of identity theft on social media. This production stood out for its unique stage direction. The characters’ social media accounts were displayed on both sides of the stage, helping the audience understand and sympathize with their psyche.

DOOSAN ART LAB, which has supported the experimental works of young artists, staged “Judith’s Arm” in March in the form of a musical staged reading. The play is based on the painting “Judith Beheading Holofernes” by Artemisia Gentileschi, of the Italian Baroque period, and follows the process of resolving why Judith’s arms are unusually thick in the painting. Set in 17th century Europe, this performance incorporated traditional Korean music, using songs and a gayageum (traditional zither), as it explores the story of the female painter and life during that period.

Staged readings are hence coming to audiences in varying manifestations and are growing more common for several reasons. First, unlike in traditional theater plays, the actors do not need to memorize their lines. Second, since the stage setting can be minimized, these readings can be done with a modest budget, and from the perspective of the audience, the reduction of visual stimuli means they can focus entirely on the actors’ voices. Despite concerns over losing the many rich and varied elements that bring stage art to completion, staged readings seem to hold their own charm and connection with the audience and are clearly helping to expand and diversify the performing arts.

A production of “Judith’s Arm,” staged this March by DOOSAN ART LAB (Doosan Art Center’s creator incubator), included a much-discussed gayageum performance. In this way, staged readings are branching out and expanding the realm of the performing arts.

ⓒ DOOSAN ART CENTER

Kim Geon-pyo Professor, Daekyeung University Department of Theater and Film, Theater Critic