Throughout the history of Korean cinema, which spans slightly more than a century, women have largely been relegated to the periphery both in front of and behind the camera. Now, a legion of female directors is gaining recognition for productions that offer their own perspectives on the world. Yim Soon-rye, Byun Young-joo, Jeong Jae-eun, Kim Cho-hee and Kim Bo-ra – these are among the prominent names at the pinnacle of this surging tide.

Yim Soon-rye: Connecting with the Audience

Yim Soon-rye has a long, prolific career as a female film director, a rare profession in itself in Korea. She has also been an active advocate for women in filmmaking, carving out her position as a symbolic figure in the industry.

Director Yim Soon-rye and the production crew for her 2018 feature “Little Forest” on location. Yim made her directorial debut in 1994 with the short film “Promenade in the Rain.” She is the sixth female director in the history of Korean cinema

Yim Soon-rye is currently working on the post-production of her latest film, “The Point Men.” Based on the true story of South Korean Christian missionaries who were held hostage in Afghanistan in 2007, the movie centers on a diplomat and a special agent’s mission to rescue hostages abducted in the Middle East. Despite unexpected setbacks from the COVID pandemic, Yim still managed to shoot major scenes in Jordan last year. Everything went smoothly, so much so that she wondered if she had used up all of the production’s good luck. The action crime film veers from her earlier works; with male stars in the leading roles, she felt there was less room for a feminist perspective. But she said, “Whenever I work on a new project, I caution against presenting characters similar to those in my previous works, and this was true again with this film.”

Yim’s filmography is famously characterized by diversity. “Three Friends” (1996), her debut feature, is about three youths struggling to make their way in society after high school; “Waikiki Brothers” (2001) brings the spotlight to a band of musicians who wander from place to place doing nightclub gigs; “Forever the Moment” (2008) is based on the true story of Korea’s national women’s handball team; “Whistle Blower” (2014) dramatizes real-life events of the fraud surrounding a professor’s human stem cell cloning experiments; and “Little Forest” (2018) is an idyllic piece about a young woman who returns to her rural childhood home to get a fresh start away from the hustle and bustle of the city. In between these incredibly diverse features, she has participated in the production of several human rights films.

Since her first short in 1994, “Promenade in the Rain,” which won the grand prize at the Seoul International Short Film Festival, Yim’s oeuvre has continued to expand and deepen. This is a result of her ceaseless efforts to find a point of connection between her films and their audiences.

She believes that just as important as meeting certain creative standards is achieving mass appeal.

“My first two movies, ‘Three Friends’ and ‘Waikiki Brothers,’ sold fewer than 150,000 tickets combined. ‘Forever the Moment’ was the first movie that opened my eyes to commercial potential,” Yim said. “Since then, I’ve tried to achieve a balance between a message and popular appeal. I must at least recoup production costs to make the next movie.”

“Forever the Moment” remains her most talked-about film, overcoming major potential setbacks. Despite the subject being handball, an unpopular sport, and the lead characters a divorcee and a mother, the movie was a surprise box office hit, attracting over four million viewers. Yim attributed its success to “meticulous planning,” giving all the credit to producer Shim Jae-myung (aka Jamie Shim), the CEO of Myung Films. As founding members of Women in Film Korea, they have performed pioneering roles together in advocating for the rights and interests of women in the film industry.

“In 1999, several women filmmakers, including Shim Jae-myung, director Byun Young-joo and I, got together at the Busan International Film Festival, and there we came up with the idea,” Yim said. “We agreed that we needed an organization to augment opportunities for aspiring female filmmakers, as well as to speak up for the rights of women in the industry.”

“Forever the Moment,” Yim’s 2008 feature, is based on the true story of Korea’s national women’s handball team and their impressive performance at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens. A surprise box office hit, the movie catapulted Yim to mainstream prominence.

Women in Film Korea was officially launched in April 2000. It has published a dictionary of women filmmakers; produced the ary, “Keeping the Vision Alive: Women in Korean Filmmaking” (2001); and hosts a festival for women cineastes at the end of each year. Asked what she thinks of the Korean film scene today as a leading female director, Yim said, “I view the sensibilities of up-and-coming young women directors and the stories they tell in an optimistic light. With that said, I also see limitations as their endeavors are not immediately translating into greater opportunities. But in the past year or two, women’s movies have become more diverse and unrestricted.”

She added that antagonism against feminist movies still persists, as shown by men “who deliberately give such films low ratings,” but she believes that the expansion of the OTT streaming market will afford more opportunities for women directors. “I want to see, and make, movies featuring characters that, regardless of gender, go about their lives without fear or dread as human beings,” she added. This is obviously the world she dreams of.

I’ve tried to achieve a balance between a message and popular appeal.”

Byun Young-joo: Filmmaker with an Avid Fandom

Back in the 1990s, long before she captured viewers’ attention for her frank and outspoken manner on TV shows, Byun Young-joo made her name as a feminist director. Rather unusually for a woman filmmaker born in the 1960s, she has a solid fandom.

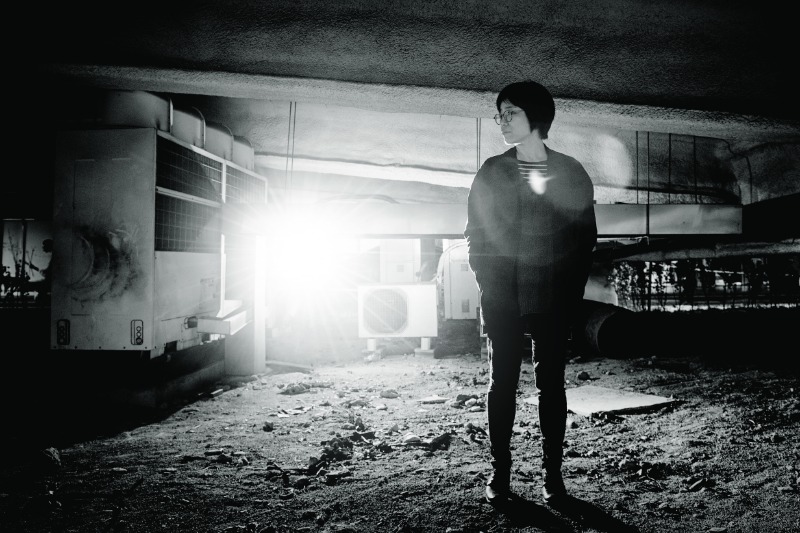

Director Byun Young-joo poses during an interview at a café in Yeonhui-dong, Seoul, in late April. She began her career in the 1990s, with a trilogy of aries about “comfort women,” victims of military sexual slavery of Imperial Japan

For her 2012 psychological thriller, “Helpless,” Byun won best director at the 48th Baeksang Arts Awards while Kim Min-hee clinched best actress at the 21st Buil Film Awards.

Byun Young-joo is a veteran director with a host of films under her belt, including a trilogy of aries – “The Murmuring” (1995), “Habitual Sadness” (1997) and “My Own Breathing” (1999) – probing the story of “comfort women” who, as young girls, were forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II; “Ardor” (2002), which portrays the precarious desires of a middle-aged, married woman; “Flying Boys” (2004), the coming-of-age story of a group of high school seniors; and “Helpless” (2012), a psychological thriller about a young woman who steals another person’s identity in an attempt to hide her past and turn her life around.

Your trilogy of comfort women’s stories garnered enormous attention at major film festivals overseas.

Actually, the trilogy received more reviews overseas than at home. In Korea, people only showed interest in the fact that it was a film about comfort women. I never intended to make films for a good cause, so I felt as if I’d been placed in the spotlight for something other than my movies. Frankly, I wanted to run away. I had completely erased those days from my memory when a director came up to me one day and reproached me, saying, “Why don’t you share your knowhow from production to distribution with younger filmmakers?” I felt so sorry. I’ve since been actively engaged in independent film events

Your first feature film, “Ardor,” depicted a young housewife having loveless sex with a neighbor after learning of her husband’s affair. It could have been controversial

When word got around that I was preparing a feature film, a ton of proposals for a comfort women movie poured in. I refused them all. My 10year career as an independent filmmaker was weighing me down and I wanted to make a film that people would watch.

You must have been worried about how to depict the sex scene.

I thought it was important to do justice to the feminine narrative of Jon Kyong-nin’s original novel, “Once in a Lifetime Day.” What I regret most about the sex scene now is that I was too focused on what I couldn’t shoot. I didn’t think about how I really wanted to shoot it. In that sense, the love scene is “defensive.”

I kept questioning myself afterward, and realized that it would have been better if I’d expressed what I wanted to rather than thinking too much about what I was forbidden from doing. I have to think about what I want to do, and then ask myself whether it’s okay, but back then, I wasn’t able to do that.

There was a long hiatus between “Flying Boys” and “Helpless.”

I’m a huge fan of both genre fiction and genre movies. After “Flying Boys,” I asked myself, “Why is there such a gap between what I like and what I make?” On a trip to Gyeongju, I read the novel, “All She Was Worth,” by Japanese writer Miyuki Miyabe. Then I purchased the film rights. My movie adaptation, “Helpless,” focuses on what turns an ordinary woman into an inhuman being. At the time, the producer told me, “Don’t try too hard to inject a meaningful message or moral into the story. It will be unwittingly projected in the film.” It came home to me what he meant while shooting.

You obviously think that a good feminist narrative or a good female character doesn’t necessarily have to be politically correct.

I’d like to see more female characters, whether passive or active, with an independent narrative regardless of how much screen time they get. I’ve pointed out the passivity of female characters because of the plethora of movies that ify women without giving them a solid narrative

I don’t have an issue with passive characters per se. The director’s gender aside, there needs to be a more diverse spectrum of women’s stories.

“The director’s gender aside, there needs to be a more diverse spectrum of women’s stories.”

Jeong Jae-eun: Ways to Convey Pain

Jeong Jae-eun’s 2001 feature debut, “Take Care of My Cat,” long preceded the boom in women’s narratives in Korean cinema. This alone assures her a place in the lineage of female directors.

“I try to refrain from going to extremes when portraying a character’s suffering or desire.”

Director Jeong Jae-eun poses during a magazine interview after the release of her 2013 ary, “Talking Architecture, City: Hall,” which scrutinizes the construction of Seoul’s new city hall building.

“There probably isn’t a single woman who studied film that wasn’t influenced by ‘Take Care of My Cat,’” a fledgling woman director once said. And it’s true that prominent women directors in Korea today nurtured their dreams watching this groundbreaking movie. The coming-of-age film captures the growing pains of five young women trying to find their way in the world.

Although initially a box office flop, the movie managed to win some devoted fans who campaigned for a second theatrical run. It was invited to many film festivals abroad, including the International Film Festival Rotterdam and the Berlin International Film Festival, where it was strongly received. The Guardian ranked the film among the top 20 classics of modern South Korean cinema.

Why did you want to tell a story about 20-year-old women in your debut feature?

It seemed like a natural progression for me, having previously made short films about an elementary school girl and then a high school girl. In hindsight, the movie was nothing less than a miracle.

Although the film didn’t do so well at the box office, it eventually attracted a loyal fan base.

The audience was diverse, and there were actually more male fans in the beginning. Men’s hostility towards feminist films wasn’t so prevalent back then. I think the male audience empathized with the struggles of the female protagonists, whereas most women didn’t want to see a movie that reminded them of the grim reality of life.

Weren’t those fans disappointed with your next feature film, “The Aggressives” (2005)?

When people asked me why I’d chosen to tell a story about men, I was perplexed. Women directors should be able to portray men in a proper light and vice versa. The movies I watched growing up didn’t necessarily lack representation of women, but male directors portrayed female characters thrown into painful situations, physically and sexually. This could be a cinematic intention to stir viewers’ emotions by displaying raw pain. But, personally, I don’t tend toward outright depiction of characters floundering in pain. I try to refrain from going to extremes when portraying a character’s suffering or desire.

A scene from “Take Care of My Cat” (2001), which captures the growing pains of five young women trying to find their way in the world after graduating from a vocational school. It is considered the first female coming-of-age film in Korea.

How did you get to direct the ary “Beast,” which was part of the “KBS Archive Project: Modern Korea” series?

KBS approached me and asked if I was interested in telling a story about women. Up until then, all episodes in the “Modern Korea” series had been directed by men. Considering the changing times, I think they wanted a woman centered story told by a woman director. In 1992, a female college student killed a man who had sexually assaulted her from a young age. “Beast” tells her story. I combined footage from various TV dramas to portray the brewing internal rage that drove the young woman to commit murder. The main audience of the series until then had been men in their 40s to 60s, but “Beast” attracted young female viewers.

Do you think the attitude of moviegoers has changed in the past 20 years?

It’s a meaningful change that young women today are becoming more responsive to works by women writers and directors. I think women’s increasing self respect and self esteem have led to this change. In that sense, I’m heartened to see more and more female protagonists who aren’t afraid to be frank about their desires. I hope to see this change in the fictional world extend to the real world.

Kim Cho-hee: The Happiness of Self-Liberation

“Lucky Chan-sil,” Kim Cho-hee’s 2019 debut feature, portrays Chan-sil, a vivacious single woman in her 40s who speaks in a local dialect, as she suddenly finds herself out of a job. The female protagonist bears a likeness to the director.

Director Kim Cho-hee talks with actors on the set of “Lucky Chan-sil” (2020), which draws from her own experience as a film producer. The lighthearted film was a success both in terms of quality and audience appeal.

There are certain types of people that you often come across in the real world but almost never encounter as lead characters on screen. Chansil is a prime example: She’s in her 40s without a husband or child and has recently lost her job. Who would want to make a movie about a woman like her?

“Lucky Chan-sil” lightheartedly flips this prejudice on its head. It begins with film producer Chan-sil suddenly finding herself out of work. But rather than despairing, she soldiers on, starting work as a housekeeper for her close friend, a young actress. Along the way, a little romance enters the picture, for the first time in her life.

Chan-sil is Kim Cho-hee’s alter ego. “I wrote the type of story I’m best at and the character just came along,” Kim explained. Her film career began as a member of the production team for director Hong Sang-soo’s “Night and Day” (2008) on location in Paris while she was studying film theory at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. She went on to work as a producer for Hong’s films for several years, but unexpectedly became jobless and was at a loss as to what to do. Eventually, she managed to pull herself up and write the screenplay for “Lucky Chan-sil.”

Kim said she felt a stark difference in the film’s reception between industry insiders and the audience. “When I pitched the screenplay to investors to receive funding, the most common response was, ‘The biggest problem with the script is Chan-sil,’” she recalled. “They thought the story was too personal. On the other hand, the audience fell in love with the character. It could be that moviegoers are the least conservative group.”

Rather than spotlight Chan-sil’s accomplishments and career successes, Kim chose to focus on her dogged, independent spirit. Chan-sil says in the movie, “It’s important to dream not only of financial independence, but emotional independence.” The film also talks about finding pleasure in the small things in life and the joy of reviving a long-forgotten dream.

“That was me. Until my early 30s, I was too bent on success and getting ahead of others. Then one day, it dawned on me that I wasn’t actually cut out for that. It became even clearer when I couldn’t find work as a producer and hit rock bottom. I wanted to tell the audience how truly liberating it is to free yourself from ambitions that are out of reach,” said Kim.

“Lucky Chan-sil” was released in March 2020, when theaters were hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic. But, like the message of the movie, Kim chose to push ahead.

Another key element of the film’s narrative is the friendship between Chan-sil and the owner of her boarding house, played by Youn Yuh-jung. Kim first met Youn on the set of Hong Sang-soo’s “Hahaha” (2010) and maintained a close relationship with her.

After Youn won the Academy Award for best supporting actress for her role in director Lee Isaac Chung’s “Minari” (2020), Kim was often invited to comment as she had worked with the actress on many projects.

In a scene from “Lucky Chan-sil,” the protagonist, who has just lost her job, moves to a rented room on top of a hill. Her tenacious spirit resonated warmly with audiences.

“I almost feel like her spokesperson,” Kim said. “Youn is an assiduous actress who demonstrates that luck played no part in the career heights she has reached. I’ve never seen her get a single line wrong. She has experienced many twists and turns in life, so her acting has extraordinary insight.”

Kim is currently working on her next title, a romantic comedy about a man and a woman with mental issues. “It seems I’m walking the same path as commercial film directors,” she said. This means that once the first draft of the screenplay is completed, the arduous process of feedback and revisions begins, which may take several years.

“I prefer movies that hint at the director’s perspectives over ones that offer sheer dramatic enjoyment,” Kim said.

“I wanted to tell the audience how truly liberating it is to free yourself from ambitions that are out of reach.”

Kim Bo-ra: Personal Narrative Illuminates an Era

“House of Hummingbird,” Kim Bo-ra’s 2018 feature debut, probes how an individual’s personal narrative can illuminate the times and aspects of society. The film garnered over 60 awards at home and abroad, bringing its director into the limelight.

During an interview in 2019, Kim said she intended “House of Hummingbird” to be a “letter from 1994” delivered to the people of today.

“Movies directed by women are often lumped together even though we are all starkly different.”

Director Kim Bo-ra’s 2018 debut feature “House of Hummingbird” looks back on an era through the narrative of 14-year-old Eun-hee.

What difficulties did you face making “House of Hummingbird”?

I approached eight or nine investors with my script and plan. Most of them said that a middle school student as the lead wouldn’t work. Many people also asked why it was so important to include the collapse of Seongsu Bridge in the story’s background.

Why did it have to be a middle schooler?

The so called “middle school second year disease,” often translated as “eighth grader syndrome” in English, is a universal phenomenon. Ages 14 to 15 are an awkward period in life, sandwiched between childhood and adulthood, when you’re just starting to open your eyes to the world. In middle school, you’re flooded with so much new information that you find it hard to assimilate, feeling confused and lost; in high school, you become more socialized and acquire a “protective color”; in your 20s, that color becomes your identity; and in your 30s, it becomes rock solid. That’s why the protagonist had to be a middle schooler.

But I had a clear picture of what I didn’t want the character to be like. The middle or high school girls in male directed films tend to be sexualized, with pretty looks and short skirts, and behave too nicely to middle aged men. They are portrayed as innocent kids who burst out laughing at the silliest things. The middle school girls I see around me couldn’t be more different. That’s why I wanted to a character who was a three dimensional human being with complex emotions.

What was the response to the movie at international film festivals?

At the Berlin International Film Festival, people told me that despite the long running time, the movie didn’t feel overly long thanks to its tight plot. I was enthusiastically welcomed at the Tribeca Film Festival because it was the first time that a feature film directed by a Korean woman had been invited to the competition section for Best International Narrative Feature. The movie made the rounds on the global festival circuit in 2018, when the industry was shifting toward greater gender balance in the wake of the Me Too movement. We were warmly received and foreign media ran articles introducing works by Korean women directors as part of a new wave in Korean cinema.

You believe the personal narrative of a young girl can serve as a window into Korean society and politics.

People like to attach the label “feminism” or “women’s solidarity” to the film, but I didn’t make it with that in mind. I’m a feminist, so I guess feminist elements inevitably seeped into the movie.

From my personal experience, the only demographic groups genuinely interested in politics are women and minorities. They have no choice but to take an interest as they are subject to systemic, societal disadvantages in everyday life.

Do you mind being called a “female” director and your film classified as a “female” director’s work?

Movies directed by women are often lumped together even though we are all starkly different. But I don’t expect to see this practice rectified any time soon. Because there’s been such a paucity of women-centered narratives, for now, there’s little choice but to draw attention by highlighting the difference from men’s narratives.

You want to make a war movie from a female perspective. Why?

I’ve been interested in war since my mid-20s. Learning about the acts of brutality committed by the South Korean military during the Vietnam War made me think about the peculiar position of women from a perpetrating nation. I also feel that war hasn’t been dealt with properly in our society. To get to the source of Korean people’s pain, we need to go back to the Korean War.

You’re working on a sci-fi film titled “Spectrum,” based on the novel by Kim Cho-yeop.

There are science fiction movies like “Interstellar” that are based on scientific knowledge, and others that borrow the genre to pose questions about what it means to be human. “Spectrum” is closer to the latter. I’m currently writing the screenplay, with the aim to start shooting next year.