Dancheong, the traditional Korean art of decorating buildings with intricate patterns, has been used since ancient times to preserve wooden structures. It began to flourish with the introduction of Buddhism in the 4th century and continues to this day. Artist and dancheong artisan Park Geun-deok has been involved in cultural heritage restoration for 20 years and reinterprets the traditional art’s motifs and designs in her own original style.

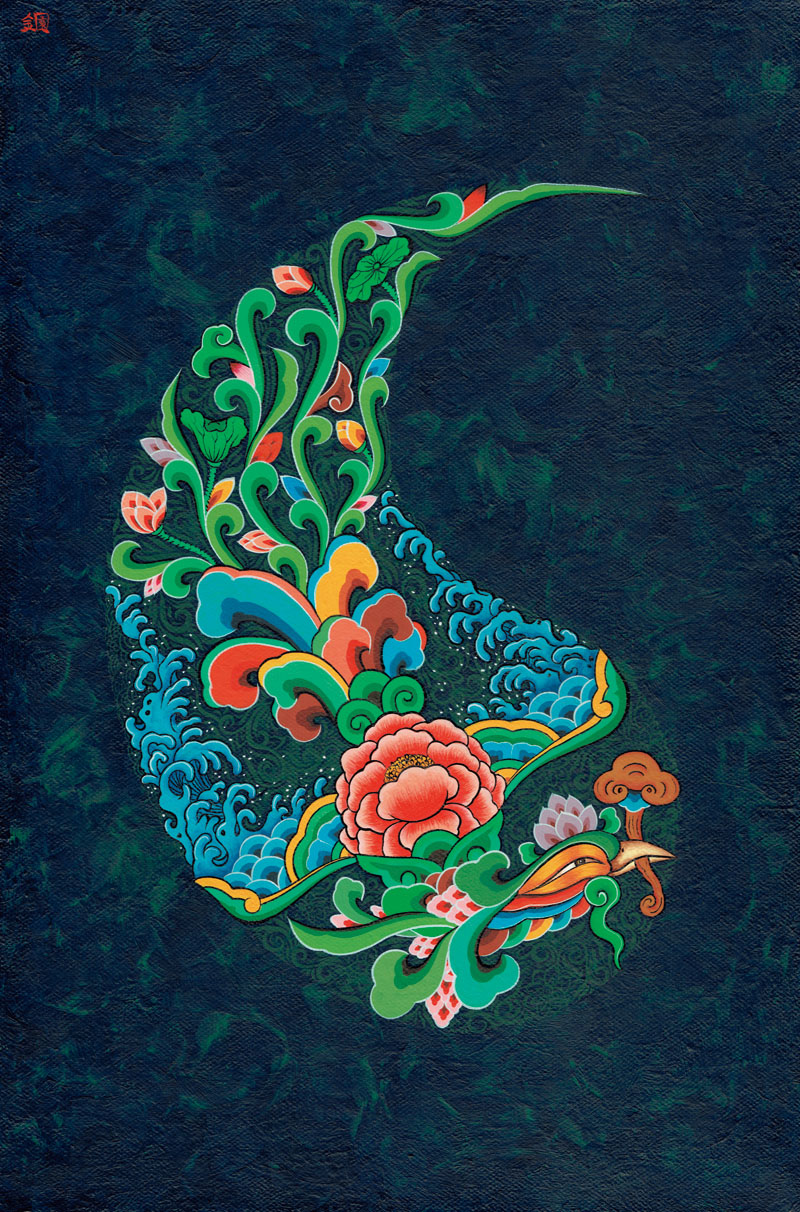

Goldgarden Ⅱ― Peony. 2018. Pigments and gilt on silk fabric. 25 × 38 cm.

Courtesy of Park Geun-deok

The splendor of Korean palaces and Buddhist temples is owed to the vibrant colors and patterns of dancheong. This form of decorative painting was originally used to protect wooden structures vulnerable to changing weather conditions, improving their durability by shielding them from heat, cold, moisture, and more. It was also used to denote architectural hierarchy with different color schemes representing the authority of royal power, religious sanctity, and other values.

As dancheong artist Park Geun-deok explains, “Dancheong is likened to clothing for buildings. Just as the attire of kings and courtiers differs, so does the ornamental coloring according to the building’s purpose and significance.”

Reflecting the influence of Buddhism, dancheong can be seen in Korea and other countries with Buddhist heritage, including China, Japan, and Mongolia. The style varies from country to country; in Japan it is mainly red, and in China predominantly blue and green. In Korea, on the other hand, buildings are adorned with obangsaek, the Colors of Five Directions — blue, red, white, black, and yellow — representing east, west, south, north, and center, respectively. This is based on the theory of eumyangohaeng, yin and yang and the five elements of metal, wood, fire, water, and earth. The paint emphasizes the contrast between complementary colors, alternating between warm and cool or bright and dark tones, which helps maximize vibrancy.

Park Geun-deok has been committed to presenting her work publicly ever since her first solo exhibition in 2022, which earned her acclaim for her modern reinterpretation of dancheong. Apart from the classic motifs of this traditional artform, Park enjoys painting wildflowers and other s commonly found in her surroundings.

COMBINING PATTERNS AND COLORS

The painting process begins with ensuring an even surface. Any gaps or holes in the wood are filled and smoothed with sandpaper, and then agyo, traditional cow hide glue, is applied two or more times. Next comes a base coat of natural pigment, such as celadonite or red ocher. A design is drawn on paper and the patterns’ outlines are pierced with a needle at regular intervals. Then, the paper is placed on the surface of the wood to be painted and tapped with a bag filled with shell powder along the punched lines to copy the patterns on the wood’s surface. Once the colors are prepared, they are applied according to the design. Finally, the shell powder is brushed off and linseed oil is applied for finishing.

Dancheong can be broadly divided into four styles of increasing complexity. The simplest involves only a single base color without any patterns. This is used for public buildings of lesser importance and private homes, but also for palace buildings of the highest rank to express their solemnity. A notable example is Jongmyo, the royal ancestral shrine of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). The second style consists of a single base color and some lines drawn along the borders. It is used to decorate subsidiary buildings, such as ancestral shrines in temples and Confucian institutions, in order toan atmosphere of formality. The third style features patterns drawn at both ends of buildings’ supporting beams, leaving the middle with only a base color. This style is widely used for different types of architecture, such as the auxiliary buildings of temples, palace halls, Confucian academy lecture halls, and pavilions. The patterns used in this style are called meoricho, beam-end patterns, whose complexity depends on the building’s prominence. The final and most elaborate style, used mostly for the main halls of Buddhist temples, involves covering the entire surface of the wood with intricate patterns to maximize splendor.

Green natural pigment is the most frequently used material in dancheong. All pigments are ground in a mortar and then strained through a sieve before coloring. The finer the particles, the lower the saturation.

“Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, a vast collection of records of state affairs, has an entry that mentions Confucian scholars petitioning to ban the use of ornamental painting for private homes. Dancheong was considered so luxurious that even royal palaces weren’t decorated in the most elaborate style. This was partly due to the influence of Confucianism, which emphasized modesty, but also because the raw materials for painting were, and still are, very expensive minerals,” Park explains.

The most common dancheong pattern is yeonhwa meoricho, the beam-end lotus pattern, which incorporates the motifs of a lotus blossom, pomegranate, and green flowers. It is often found on subsidiary buildings in Buddhist temples and royal palaces, Confucian educational institutions, such as hyanggyo (public schools) and seowon (private academies), and other common structures, such as pavilions.

“I also use this pattern a lot in my work,” Park says. “Sometimes I paint it in the traditional style, and sometimes I modify it a bit by replacing the lotus blossom at the center with motifs of local wildflowers, such as Korean dandelion and Thunberg’s smartweed.”

The fabric canvases, made of ramie, silk, and hemp, are dyed naturally by Park herself. The woven structure of the cloth makes it difficult to produce precise color tones on the first attempt, so they are dipped in dyes and then dried repeatedly until the desired result is obtained.

CREATIVE APPLICATIONS OF TRADITION

Park held her first solo exhibition, Goldgarden, at GALLERY IS in 2022. Since then, she has been praised for her original dancheong reinterpretations, which she has presented in annual exhibitions. Last year, she won the grand prize at the Buddhist and Folk Paintings Contest hosted by Gallery Hanok, and was recognized for her paintings of flora and fauna motifs at the invitational exhibition During the Colorful: The Innocent Elephant, held at Moo Woo Soo Gallery.

At the invitational, Park displayed dancheong-inspired works depicting, for instance, an elephant adorned with a headpiece in the shape of lotus and dandelion flowers, and a whale similar to those in the prehistoric Bangudae Petroglyphs in Daegok-ri, a village in Ulsan. Her other paintings were equally striking: phoenixes with wings expressed with ocean waves instead of flames, fish decorated with endangered indigenous plants, as well as radishes and carrots native to Jeju Island exquisitely depicted on silk fabric.

“Traditionally, the most popular dancheong motifs are lotuses, peonies, and other flowers with symbolic meanings. However, when working on my personal projects, Idesigns based on my favorite flowers or wild grasses commonly found in nature. Traditional patterns have a number of interconnected motifs, but I tend to unravel and combine them in my own way. I find these experiments quite enjoyable,” Park says.

The artist also describes how working on her original paintings gives her a sense of freedom, especially when she feels constrained by the rigorous nature of cultural heritage restoration work, with no margin for error.

“Cultural heritage sites are usually located in scenic places. Taking a walk in the natural surroundings away from the work site is truly relaxing. My eyes are drawn to everything; even a blade of grass, stones, or tiny flower petals are never missed. When I look at them closely, I realize that each of the natural s contains a world of its own. I started working on my personal projects to use the images of these moments in my original patterns.”

Goldgarden ― Phoenix. 2018. Acrylic on canvas. 40 × 26 cm.

The phoenix is a mythical creature believed to appear during times of peace. The artist depicted

its wings using wave patterns.

Courtesy of Park Geun-deok

SOURCE OF INSPIRATION

As a cultural heritage repair engineer, Park directs and supervises the work sites of cultural heritage repair technicians, who are predominantly male. In 1999, she enrolled at Dongguk University to study Buddhist art. Immediately after graduating, she began working in cultural heritage restoration, and since acquiring her license in 2022, has also supervised dancheong painting at various sites.

“I learned the basics of my work from scratch at the actual work sites, but I felt my knowledge was limited. So, I went to graduate school and obtained a qualification as a dancheong artisan. Most artisans who have learned the craft through apprenticeship are reluctant to accept college graduates. When they meet a newcomer, they start by asking, ‘Who did you work for?’ or ‘Which master did you study under?’ Depending on which master’s cho [patterns] you used for your training, you automatically belong to a certain school. I used to find this suffocating at times, but I now have a wide network that allows me to learn various techniques and skills while working at many different sites,” Park explains.

Since most heritage restoration projects are government commissions, all procedures are carried out by strictly adhering to design plans. Occasionally, when an error in the design is found at the restoration site, one of Park’s main responsibilities is coordinating between the client and the site to revise or re the design.

“When it comes to preparing colors, for example, there are textbook-like manuals for other genres such as painting and gilding, right down to the proportion of pigments and glue. However, dancheong relies more on extensive experience, as a wide range of conditions like the location of the building and the climate must be taken into account.” As Park expounds, dancheong requires a comprehensive skill set that includes painting, calligraphy, drawing, and handicrafts. This is what attracted her most to the art.

Goldgarden VII ― 20190421. 2022. Pigments and gilt on naturally dyed cotton fabric. 116.8 × 72.8 cm.

The elephant’s ears and nose are filled with classic dancheong patterns used on palace and temple buildings. They were inspired by elephants the artist saw during a trip to Sri Lanka.

Courtesy of Park Geun-deok

“The job of a dancheong artisan includes repairing Buddhist murals that are often found at temples. These murals are mostly paintings of sacred scenes, but they also feature landscapes, Sanskrit words, mountain gods with tigers, and other imagery. Therefore, the artisan should have a broad knowledge of Buddhist art, including calligraphy, religious murals, flower and bird paintings, ink wash paintings, and so on.”

Park is thrilled whenever she looks at the brushstrokes left on old buildings by people from the past. Her work brings her genuine happiness, which is, in turn, the source of her inspiration and creativity.