Postwar Korea adopted a ppali, ppali (hurry, hurry) mindset that remains embedded in its society today. But during winter, if you head to Muju County, deep in the southern interior of the Korean peninsula, you will encounter a hidden side of Korea that offers a respite from the frenetic pace.

© KOREA TOURISM ORGANIZATION

Mt. Deogyu is one of the most beautiful mountains in South Korea. In winter, trees are draped in a stunning blanket of hoarfrost, a product of repeated cycles of melting and freezing.

© Lee Jae-hyung

A Trip to Muju County in North Jeolla Province is an opportunity to revel in the charm of the Korean winter and opens your eyes to the beauty and value of nature. The highlight of a visit here is the topography of Mt. Deogyu National Park. The mountain, whose name means “abundance of virtue,” stretches for more than 30 kilometers, partly covering Muju County and anchoring Baekdudaegan, the north-south mountainous spine of the Korean peninsula.

Hyangjeokbong, Mt. Deogyu’s central peak, towers 1,614 meters above sea level and is complemented by numerous ridges with peaks more than 1,300 meters high, some 20 large and small waterfalls, dozens of ponds, and 13 famous observation platforms.

Below, Gucheondong Valley, whose name stems from a serpentine stream that flows through it, is known for its breathtaking scenery which draws visitors all year round. The most spectacular spots are collectively known as the “33 Vistas of Gucheondong.”

GLASSY LANDSCAPE

Mt. Deogyu is famous for its ski resort. In just 20 minutes, a cable car takes visitors close to Hyangjeokbong, the highest peak. Reservations are a must due to the steady stream of skiers, hikers, and sightseers.

© KOREA TOURISM ORGANIZATION

The true beauty of Mt. Deogyu is best appreciated on foot. In winter, the snow on the tree branches melts slightly in the day’s sunlight, then freezes again when the temperature drops at night. This repeated cycle of melting and freezing forms ice crystals known as hoarfrost that cloak trees, boulders, and rocks. From afar, the landscape appears to be encased in clear glass. The hoarfrost at Mt. Deogyu is the thickest and most transparent in the region, thanks to the mountain’s high ridges and ideal humidity and wind conditions. When you push away the hoarfrost-covered branches, they knock against each other, creating an indescribably clear sound.

Despite being the fourth-highest mountain in South Korea, it is not difficult to reach the summit of Mt. Deogyu. Inexperienced hikers can take a 20-minute cable car ride to a platform at Seolcheonbong, a peak at 1,520 meters. From there, you can overlook the center of Muju-eup, the town in the county’s north. The rest area rents out winter hiking gear, such as crampons, spats, and hiking staffs. When ready, visitors only have a 600-meter walk up to Hyangjeokbong and can enjoy the hoarfrost along the way. Gentle stairs help with the ascent.

Mt. Deogyu is also home to the only Korean ski resort located inside a national park; it boasts the biggest ski slope and the steepest vertical drop in the country. Whether you prefer hiking or skiing, you will be able to appreciate why Mt. Deogyu is considered one of the most beautiful Korean mountains to visit in winter.

The pristine natural environment around Mt. Deogyu and Muju County is simply breathtaking. The annual Muju Firefly Festival in early autumn celebrates the large firefly habitat by Namdaecheon, a stream that flows through the northern part of Mt. Deogyu. At night, the fireflies illuminate the area in a massive mating ritual. In 1982, Muju’s habitat of fireflies and their prey was designated as Natural Monument No. 322.

CONSERVATION

At the Muju Firefly Festival, visitors can observe fireflies in their natural habitat and participate in eco-adventures. Set in a pristine environment, the festival promotes the peaceful coexistence of humans and nature.

© KOREA TOURISM ORGANIZATION

Environmental protection efforts in Korea began in earnest in the 1960s. In 1963, the National Reconstruction Movement Headquarters proposed that the government bestow national park status onto Mt. Jiri, to the south of Mt. Deogyu. The following year, residents of Gurye County near Mt. Jiri promoted and raised funds for the plan. Their efforts paid off in 1967, when Mt. Jiri was designated as the country’s first national park. Mt. Deogyu gained national park status in 1975, making it the tenth Korean national park at the time.

The Korean fir, which grows at an altitude of 1,300 meters at Mt. Deogyu, is familiar to most Koreans as it is a popular Christmas tree. The tall European spruce may be a more common choice for outdoor Christmas trees, but the Korean fir is preferred indoors because of its smaller size and the larger spaces between its branches, which allow for more room to hang decorations.

Unfortunately, the Korean fir may become a rare sight. In 2013, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classified it as an endangered species. To protect it, Yuhan-Kimberly, Ltd., a joint venture of Korean pharmaceutical company Yuhan Corporation and U.S. paper-based consumer product giant Kimberly Clark, launched a Korean fir conservation project with the Baekdudaegan National Arboretum in 2021. The initiative can be compared to building a “Noah’s Ark” for the imperiled tree. Nearly 6,800 seedlings are being grown in the arboretum’s greenhouse, and 120,000 Korean fir seeds were collected in 2022 to further increase this number. The plan is to transplant young Korean firs onto Mt. Deogyu.

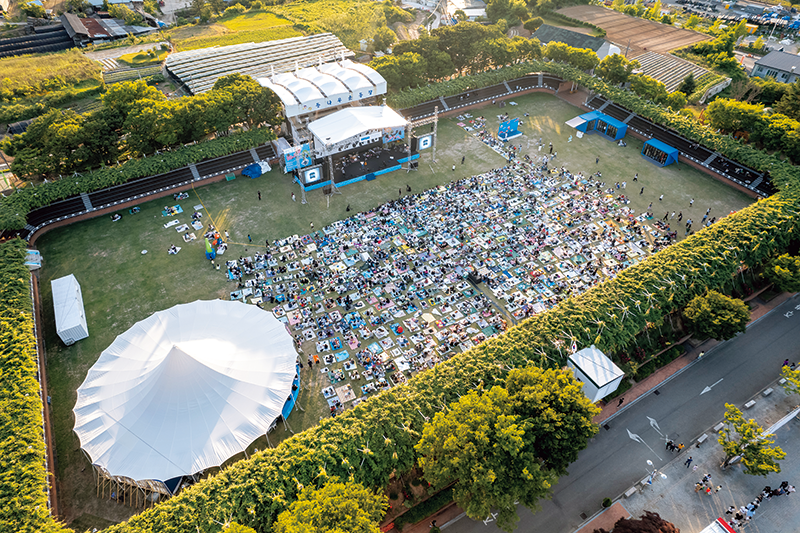

The Muju Film Festival held at Muju Deungnamu Stadium. Some 500 wisteria vines reach all the way up to the roof of the bleachers and provide a natural shade for spectators.

© Muju County

“BACKUP” SITE

There is another place in Muju that is dedicated to preservation. It is the royal historical repository on Mt. Jeoksang, which is located inside Mt. Deogyu National Park. The Joseon Dynasty, which ruled Korea from the late 14th to the early 20th centuries, placed great importance on keeping historical records. The purpose was to prevent the tyranny of the king, who wielded absolute power, as well as to pass down knowledge and expertise to future generations. The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, which contain daily accounts encompassing 472 years of the dynasty’s history, are the most prominent record. They are not only the longest-running historical record of any single dynasty in the world, but the only case where the original volumes remain intact to this day. In recognition of their value, they were designated as a national treasure of Korea in 1973 and inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 1997.

How could the annals be preserved in their original state over many centuries, surviving wars, fires, and countless natural disasters? This can be attributed to the Joseon government’s efforts of creating several “backups.” One set was kept in the capital and another three or four in different places across the country. In addition, every three years, the books were aired under the sun to prevent mold growth and damage from silverfish.

The annals faced dire situations. At the end of the 16th century, when Joseon fought off Japanese invasions with the help of Ming China, all but one copy of the annals were destroyed in a fire. The surviving copy had been stored at the Jeonju repository, about 50 kilometers southwest of Muju, and the government later restored the original number of five copies and dispersed them to repositories across the nation. One of them was the repository on Mt. Jeoksang, an ideal location thanks to its proximity to a cliff that could provide protection from invaders. In addition, Mt. Jeoksang Fortress, which had been built 1,500 years earlier, was reconstructed to fortify areas with gently sloping terrain.

In the early 20th century, the annals that were stored at the Mt. Jeoksang repository were relocated to Seoul, but they mysteriously disappeared during the Korean War. Despite this loss, the extensive collection, comprising a total of 1,893 volumes and 888 books, has been passed down from generation to generation, thanks to the dedicated efforts tobackups.

Taekwondowon is dedicated to taekwondo, the traditional Korean martial art, with facilities for competitions, training, education, and research. It also offers a “taekwondo stay” to the general public.

© Muju County

HARMONY WITH NATURE

Muju is not just a travel destination; it is also a place providing a deeper understanding of the breadth and depth of Korean society’s efforts to coexist with nature. One example is Muju Deungnamu Stadium in the southern part of Muju-eup. It was designed so that the 500 or so wisteria vines that climb up its steel frame provide spectators with shade during summer and shelter from the snow during winter.

Modern architecture places more emphasis on practicality and functionalism, but there is one aspect it frequently overlooks: the interaction between humans and nature. Modern architecture tends to exude an overbearing aura as if wanting to dominate nature, and landscaping can be seen as an effort toan artificial form of nature. The stadium’s architect, Chung Guyon (1945–2011), had a different idea. Rather than artificially transforming and utilizing nature as an architectural component, he let nature take center stage.

Nature is constantly changing. Flowers bloom in spring, trees become lush in summer, leaves fall in autumn, and trees turn bare in winter. The architect used wisteria, whose branches are beautiful even when bare, toa stadium that connects with nature. Taking the stairs up to the bleachers and walking behind the back row reveals the beauty of the stadium.

A trip to Muju is an opportunity to discover that Korean society has not been completely focused on moving forward at breakneck speed. It has also sought ways to interact and live in harmony with nature. As winter is coming to Muju, there is no better time to enjoy its rich history and natural beauty.

From left, © Muju County, © Muju County, © Muju County, © KOREA TOURISM ORGANIZATION