Choi Wook-kyung (1940-1985) was a prominent abstract painter who embraced new international art trends. An extensive retrospective titled “Wook-kyung Choi, Alice’s Cat” was held from October 27, 2021 to February 13, 2022 at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Gwacheon.

To most people today, Choi Wook-kyung is not a familiar name. Like Park Re-hyun (1920-1976), for whom the MMCA held a large-scale posthumous retrospective on the the centennial of her birth, it seemed that Choi’s name would be forgotten soon after her sudden death – a consequence of art history being written mostly from the male perspective. Revisiting the trajectory of Choi’s life as she vigorously built her identity in art and literature from the 1960s to the 1980s, traveling back and forth bet ween Korea and America, is tantamount to filling a void in Korean women’s art history and, eventually, rewriting Korean art history itself.

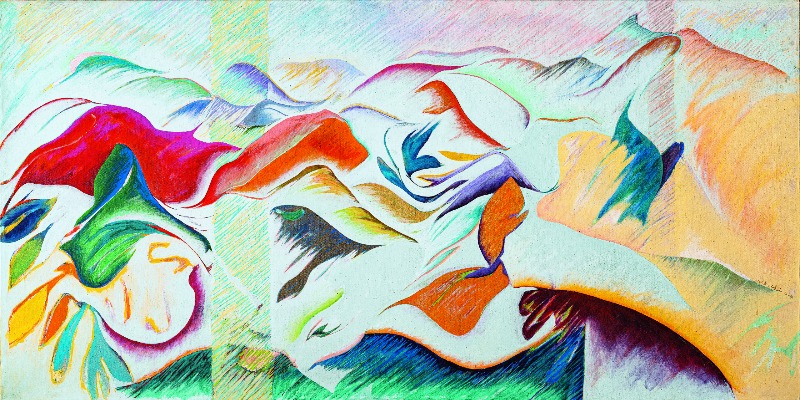

“Tightrope Walking” 1977. Acrylic on canvas. 225 × 195 cm. Leeum Museum of Art.Choi Wook-kyung’s paintings from the mid- and late 1970s are characterized by the vibrancy created from the mixture of organic shapes resembling flowers, mountains, birds and animals.

“Martha Graham” 1976. Pencil on paper. 102 × 255 cm. Private collection.A large pencil drawing inspired by the performance of American contemporary dancer Martha Graham. The white shape with wings stretched out as if dancing, or flying, has a lofty, epic feeling.

To a Bigger World

The exhibition comprised three themes arranged in chronological order, with an epilogue featuring portraits and archival material shedding light on the artist’s world. In the last section, visitors found the “college prep art” that Choi learned while attending Seoul Arts High School. Her paintings from those early years did not show her individual style so much as the conventional techniques handed down from the colonial period. As a Western painting major at Seoul National University, she submitted her artworks in competitions and received prizes, which brought her to the attention of the art circle. But until she went to study in America, her work most probably remained an extension of the art education she had received to get into university.

Choi had taken private lessons from famous painters from her middle school days. The training method in those days was largely in line with the customs of patriarchal hierarchy, so she was likely required to follow the styles of her teachers. In an interview with the Korea Herald in 1978, she pointed out the fundamental differences between American and Korean art education, saying that the former respected the identity of individual artists’ works.

The MMCA retrospective included a poem titled “An Old Story that My Mother Told Me,” which Choi wrote in 1972. In the poem, she meets a wolf in the woods and walks hand in hand with it as friends would, although her mother had told her never to look a wolf in the eye if she ever came across one, never to answer back if spoken to, and to refuse if invited for a walk. By saying that she held hands with a wolf, she probably indicated her determination to break the taboos of her familiar world and move on to a bigger world. In 1963, her life abroad began at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, a small city in Oakland County, Michigan, United States, where she experienced big changes in her work and life.

Exploring Her Identity

The first section of the exhibition, “To America as Wonderland (1963-1970),” shed light on Choi’s life as a student at Cranbrook and then as an assistant professor at Franklin Pierce College in New Hampshire. The 1960s in the United States was a period of transition from Abstract ism to Post-painterly Abstraction. Studying under Professor Donald Willett (1928-1985), whose style reflected this era of change, Choi worked on abstract paintings marked by strong brushwork and colors. Her exposure at the Cranbrook Art Museum to the works of Abstract ists such as Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock greatly helped to increase her understanding of contemporary art.

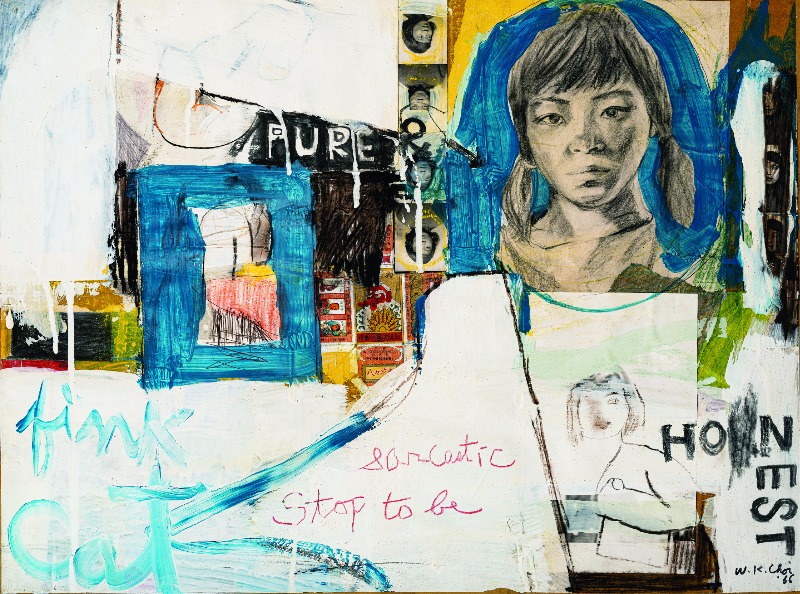

After graduating from the Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1965, she attended the Brooklyn Museum Art School in New York for one year, and then in the summer of 1996, participated in the residency program at the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture in Maine. During this period, Choi came into contact with the diverse styles and media of the East Coast, including figurative art, graphic art, print and Pop Art. Under their influence, she glued torn pieces of newspaper to her canvas, juxtaposing them with the colored surface, or coloring over magazine images. Through these methods, she attempted to express her reaction to the modernism of Neo-Dada and Pop Art.

As indicated by “Alice’s Cat” and “Wonderland” constituting the titles of the exhibition, a significant part of Choi’s art world is dedicated to Lewis Carroll’s novel, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” (1865). In 1965, when many related books were published to celebrate the novel’s centennial, Choi painted “Alice, Fragment of Memory.” “Like Unfamiliar Faces,” her poetry book published in 1972, included a poem titled “Alice’s Cat.” Curator Jeon Yu-shin, who directed the MMCA retrospective, explained it as a metaphor for a “foreign woman from Asia.” Confused about her own cultural identity, Choi could easily empathize with Alice’s story. Exploring her identity through such works as “Fate” (1966), “In Peace” (1968) and “Who Is the Winner in This Bloody Battle?” (1968), in which she spoke up against racial discrimination and war, Choi gradually adapted to American society.

The second section of the exhibition, “Korea and America, In Between Dream and Reality (1971-1978),” looked back on the period when Choi traveled back and forth between America and Korea, working in both countries. She returned to Seoul in 1971 and stayed until 1974, during which time she held two solo exhibitions and submitted three installation works, including “Curiosity” (1972), to the Independent, a competition to select artists for the Paris Biennale. It seems those works intentionally followed the trends of the times. At the same time, she was also interested in dancheong (decorative paintwork on wooden buildings), minhwa (folk paintings) and calligraphy, and experimented with different styles accommodating these traditional visual arts.

“Alice, Fragment of Memory” 1965. Acrylic on canvas. 63 × 51 cm. Property of the artist’s family.As an Asian woman searching for her artistic identity in America in the 1960s, Choi found Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” to be a source of inspiration. This is known to be her first work on the theme of Alice.

“Untitled” 1966. Acrylic on paper. 42.5 × 57.5 cm. Leeum Museum of Art.While studying in the U.S., Choi painted many self-portraits exploring her true inner self. She tried to overcome her perceived limitations as an Asian woman.

Her Own World

In 1976-1977, Choi joined the residency program at New Mexico’s Roswell Museum & Art Center. These years were another inflection point in her life, affecting significant changes in her work. She focused on large paintings, vividly expressing organic shapes resembling mountains, birds and animals, as seen in “Collaged Time” (1976) and “Joy” (1977). Inspired by the exotic landscape of New Mexico, she mixed in surreal dream scenes from “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” to develop her own painterly rhetoric. Then, back in Korea again, she held a touring exhibition titled “Impressions of New Mexico (1978-1979),” which drew critical comments about “being American.” By that time, however, Choi was headed to her own world – one that defied such a simple definition.

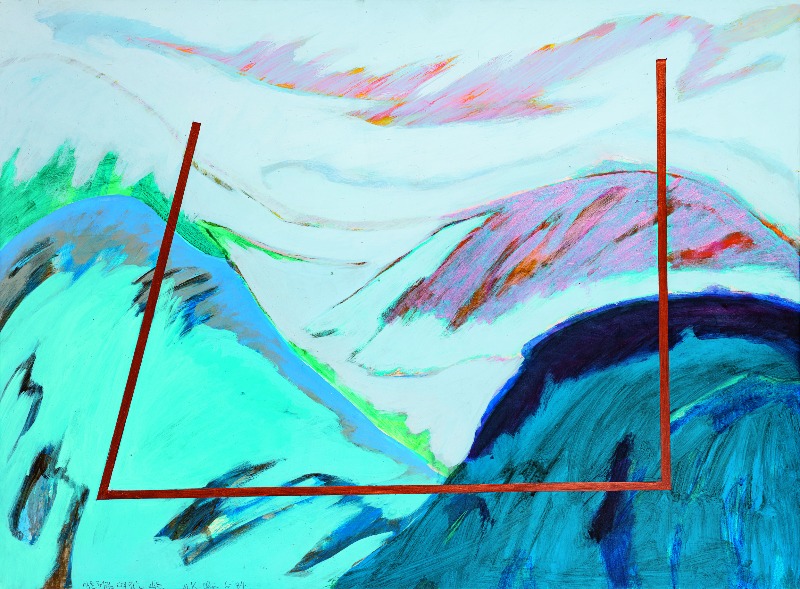

“Mt. Gyeongsan” 1981. Acrylic on canvas. 80 × 177 cm. Private collection.

“Mountains Floating Like Islands” 1984. Acrylic on canvas. 73.5 × 99 cm. Private collection.Choi returned to Korea in 1979 and taught at Yeungnam University in Daegu. She was drawn to the natural scenery of the Gyeongsang provinces and contemplated the forms of mountains and islands.

Choi poses in her studio in this photo taken in the early 1980s. Born in Seoul in 1940, she studied painting at Seoul National University and then the Cranbrook Academy of Arts in the U.S., where art was in transition from Abstract ism to Post-painterly Abstraction. She experienced the change first-hand and vigorously explored her artistic identity.

Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

The third section, “To the Mountains and Islands of Korea and the Home of Choi’s Painting (1979-1985),” showcased her works from the years she taught at Yeungnam University in Daegu and Duksung Women’s University in Seoul after returning to Korea in 1979, where she would remain until her death in 1985. Her days at Yeungnam University brought about yet more changes in her art. She painted “Mt. Gyeongsan” (1981) and “Mountains Floating Like Islands” (1984), inspired by the mountains and seas of the Gyeongsang provinces. The mid-tone colors and restrained lines and compositions give the impression that Choi was no longer confused but peacefully settled in “Wonderland.” She studied the forms of mountains and islands, and her deepening interest in the shapes and order of flower petals as well as intense colors led her to paint works like “Red Flower” (1984).

“Wook-kyung Choi, Alice’s Cat,” a large-scale retrospective at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, held from October 27, 2021 to February 13, 2022, shed light on Choi Wook-kyung, an outstanding abstract painter who was active from the 1960s to the mid-1980s.

© Gian

Lost Name

In her poem “My Name Is,” Choi calls herself a scared child with big eyes when she was little, a mute child who lost her voice among unfamiliar faces when she studied abroad, a child who lost her way chasing rainbows when she was finally adapting to her American life, and a nameless child who lost her name after she returned to Korea.

To find her name, it seems that she constantly strived to form herself in poetry and paintings. But this wasn’t easy. During the 1970s and 1980s when she was most active, the mainstream trend in Korea was monochrome painting, which shared the style of Post-painterly Abstraction. Art historian Choi Yeol said that Choi Wook-kyung had fully assimilated Abstract ism, but the Korean art circle belittled it as something passé. She must also have been confounded by the male chauvinism in the art community, which referred to Lee Krasner as “Mrs. Jackson Pollock.” There is no knowing what took the heaviest toll on her, but in 1985 she died in her mid-forties.

In 2021, the Pompidou Center in Paris staged an exhibition, “Women in Abstraction,” featuring some 500 works by 106 female artists around the world who contributed to abstract art. Three of Choi’s paintings were included. It would have been difficult to introduce the language she searched for and wished to speak through those three paintings alone. That said, the Choi Wook-kyung retrospective must be taken as a starting point for rewriting her story, as well as women’s art history.