Professor Choi Byong-hyon compares translating ancient Korean classics into English to “swimming without water,and fighting without an enemy.” His solitary battle over decades has finally earned recognition with the publication ofhis works by prestigious university presses in the United States. The National Academy of Sciences acknowledged hisefforts at producing essential texts for Korean studies programs overseas by presenting him with its 2016 annual award.

Professor Choi Byong-hyon, director of the Center for Globalizing Korean Classics,forges ahead with the translation of Korean classics into English with the mission ofaddressing the lack of available works in this field.

Some say it is the translator’s lot in life to be invisible. It isconsidered a professional virtue: all attention should fall onthe original work. At times, the translator comes to the fore,as witnessed recently when “The Vegetarian” by the South Koreannovelist Han Kang received the 2016 Man Booker InternationalPrize. The prize was awarded to both Han and her novel’s Britishtranslator Deborah Smith, but those working in the classics largelygo unnoticed.

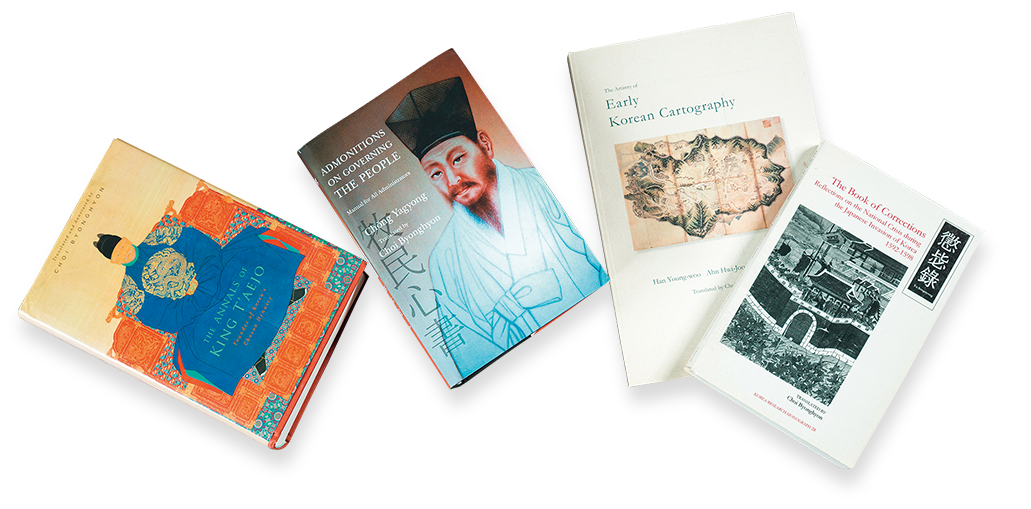

“Without notice, without a name” is how Professor Choi Byonghyondescribes the situation. Working alone in his office at HonamUniversity in Gwangju, over the past 20 years he has quietly translatedsome notable Korean classics: “The Book of Corrections:Reflections on the National Crisis during the Japanese Invasion ofKorea 1592–1598” (Jingbirok), “Admonitions on Governing the People:Manual for All Administrators” (Mongmin simseo), and “TheAnnals of King Taejo: Founder of Korea’s Choson [Joseon] Dynasty”(Taejo sillok).

Poet, Novelist, Translator

“If I hadn’t been a professor at a regional university, all of thiswould have been impossible,” Choi says. “It was quiet. Nobodybothered me. My office was beautiful. I had a lovely view of the surroundingforest. You could say that the time was long, you could alsosay it was short. Anyway, I wrestled with those texts all those years,and last year I retired [from the university].”

Despite the serenity of his words and the look of peace on hisface, the massive tomes were by no means easy to produce.

“The Book of Corrections” (2002, University of California, Berkeley)is a war memoir written by the Joseon Dynasty scholar andchief state councilor Ryu Seong-ryong, who directed state affairsduring the Japanese invasions of the late 16th century. Its translationtook four years to complete.

The second work, “Admonitions on Governing the People” (2010,University of California Press), was written by the scholar-officialJeong Yak-yong, a leading propounder of Silhak, or “Practical Learning.”A manual for local officials, it contains examples of corruption,and deals with topics such as taxation, justice, and famine relief.Running over a thousand pages, it took Choi 10 years to complete.

Jeong Yak-yong had lived inside Choi’s head and heart for such along time that during a commemorative lecture he gave in Gangjin,where Jeong wrote the book during his 18 years in exile, Choi had avision of the Joseon scholar sitting in the audience, dressed in a traditionalcoat. “It was a strange experience,” Choi recalls, wonderingabout it even now. For his translation, a 10-year endeavor, Choireceived a grant of 20 million won (about $18,000).

The most recent publication, “The Annals of King Taejo” (2014,Harvard University Press), is the official chronicle of the reign of YiSeong-gye who founded the Joseon Dynasty in 1392. This translationalso took four years.

In addition to working with the original texts, Choi wrote extensivefootnotes to aid readers’ understanding. There were countlessnames of government offices and positions, hard to understandeven in Korean, for which he had to find English equivalents. TheInternet offered little useful information.

At this point, one can only wonder why he started on this path inthe first place.

At the time, Choi had a stable job as professor of English literatureat Honam University and was also an award-winning poet andnovelist. His first poetry collection, “Piano and Geomungo,” writtenin English at the age of 27 while studying at the University of Hawaii,won the Myrle Clark Award for Creative Writing in 1977. His novel“Language,” written in Korean, won the first Hyun Jin-geon LiteraryAward in 1988.

When he wrote “Language,” Choi was studying for his master’sdegree in English literature at Columbia University, a time that hedescribes as the most difficult in his life. While serving his mandatorymilitary duty in the 1970s, he spent a week on his knees aspunishment for voting against the dictatorial government’s YushinConstitution and suffered through the investigation of his family andothers close to him. When he went abroad to study he swore neverto return. In America he came under all kinds of new influences. Inthe 1980s deconstructionism was all the rage. Choi began to wonder,“Why has language itself never been the main character of anovel?” and through language he began to deconstruct everythinghe had known up to that point. The resulting “poetic novel” featuresthe rhythms of traditional pansori and modern rap. Its leadingcharacters, named Sa Il-gu (April 19), Oh Il-yuk (May 16), and SamIl (March 1), are textual symbols of major resistance movements inmodern Korean history. “Language” was the synthesis of many ofChoi’s ideas about politics, language, and literature.

Choi envisioned bringing together East and West, as suggestedin the title “Piano and Geomungo.” One of his poems in the collection,“Confession,” contains the line, “Why did I choose the way Icannot tell.”

“I thought I would integrate English literature and world literature,”he says. “I didn’t know it would take the form of classicstranslation.”

Selecting the Texts to Translate

In 1997, Choi was invited to teach every Saturday at the Koreacampus of the University of Maryland. “I taught English literature inthe morning and Korean literature in the afternoon. English literaturewas relatively easy because there was a lot of good material.But Korean literature was difficult. It was tedious, because therewere no texts available in English,” he recalls. “So for every class,I began translating parts of the texts that I wanted to use, Goryeoperiod literature such as Pahanjip (Collection of Writings to DispelLeisure), for example.”

Later, while teaching Korean literature at the University of California,Irvine, as a Fulbright scholar, he ran into the same problem.One of Choi’s beliefs about learning is that it should be put to use,and it seems this led him to what he calls his “manifest destiny.”

“I realized what I had to do — English literature not for the sakeof English literature but using it as a springboard for making Koreanculture and history known around the world. And as soon as Istarted to think that way, I started to torment myself,” Choi sayswith a rueful smile.

In selecting the texts to translate, Choi decided that the mostimportant thing was to convey the voice of the Korean people. Thenhe set down two principles: themes that are local and universal;and contents that are timeless and temporal. Hence his first choicefell on “The Book of Corrections,” which shows a leader’s wisdomin a time of national crisis and holds lessons for future generations.At the time he was translating the book, Korea and other countrieswere reeling under the Asian financial crisis. “Near the end ofthe 16th century people did not understand why Hideyoshi invadedJoseon. The same with the financial crisis of 1997. No one reallyunderstood why it happened. In both cases, people were busy passingblame. It was the perfect text,” Choi says, explaining his choice.

Translation of this book and those that followed was, in Choi’swords, “Like swimming without water, and fighting without anenemy. Every birth was difficult.”

The search for Korea’s heroes appears to be another guidingprinciple in Choi’s translation of the classics. In seeking to “directlyrevive the voice of our ancestors,” he has brought to life Ryu Seongryong,Jeong Yak-yong, and King Taejo for an international readership,and he hopes to bring attention to many others. At home, theyare popular historical figures whose lives have been dramatizedoften in movies and television series. “They were value-orientedand goal-oriented — men with a mission,” he says. These Koreanclassics may not have the romance and excitement of the “Iliad” orthe “Odyssey,” but shining through them is a spirit that Choi definesas integrity.

“I realized what I had to do — English literature not for the sake of English literature but using it as aspringboard for making Korean culture and history known around the world. And as soon as I startedto think that way, I started to torment myself.”

The Mission Imposed on Himself

Choi, no doubt, has a mission of his own — the globalization ofKorean classics. As director of the Center for Globalizing KoreanClassics, he wants to make Korea’s heroes famous outside the countryalso. Fortunately, all his translations have been published byprestigious university presses in the United States after passing theirrigorous standards. Thanks to the universities’ distribution systemsand influence, the books are now found in university libraries aroundthe world, and are must-read texts in all Korean studies programs.

The books have also caused quiet reverberations at home, raisingawareness of the need to encourage work in the classics. In2014, Choi was asked to head the (now-defunct) Center for KoreanClassics Translation at Korea University. There he worked with ateam of scholars on “Discourse of Northern Learning” (Bukhakui)by Park Je-ga, scheduled to be published in 2017. This year he wasasked by the Poongsan Group to write a biography of Ryu Seongryong,author of “The Book of Corrections,” who is a direct ancestorof the group’s founder. Though yet to be written, the biography hasalready been titled “Ryu Seong-ryong, Heroic Minister of Korea.”

Heroic in what sense, one may ask. “How can a scholar-officialbe a hero?” Choi answers: “The concept of a hero is differentbetween the East and the West. In the West the hero is a warrior. Inthe East the hero is a scholar, the Confucian ideal of the ‘superiorman’ (gunja, or junzi in Chinese). The true meaning of a hero lies inspiritual rather than physical power.”

The new book will be written in English. Thanks to his work anda total of 18 years studying and living in the United States, Choi isjust as comfortable with English as with Korean. More so perhaps,because English, he says, has a flavor of its own, “That particularcleanness.” The great thing about his translations is that they areeasy to read. In wonderfully clear English, they make accessible primarysources that are actually rather daunting in their original Chineseor Korean language versions. This clarity is based on Choi’sexpertise in the subjects covered by his material, ranging from politics,war, and Confucianism to agronomy, geography, and the arts.

While teaching English literature over the past 20 years, Choi Byong-hyon has alsomanaged to translate some important classics, such as "The Annals of King Taejo:Founder of Korea's Choson Dynasty," "Admonitions on Governing the People: Manualfor All Administrators," "The Artistry of Early Korean Cartography," and "The Book ofCorrections: Reflections on the National Crisis during the Japanese Invasion of Korea1592–1598." These are precious resources for Korean studies scholars.

Every year as October draws around, Korea tends to tense upwhen the winner of the Nobel Prize for literature is announced. Butrather than making a fuss about the elusive Nobel Prize, Choi advocatesa change in the country’s international profile through the globalizationof its classical works. “If they want to give Korea a prizefor any modern literature, first they will want to know about thecountry’s roots,” he argues.

The biography is a step in that direction. His model is the JohnAdams biography by David McCullough, among others. This maybe a move away from classics translation for himself, but having“cut the cord,” he hopes many others will take up the work. It’s atall order. Funding for classics translation is limited and in-depthknowledge of classical Chinese and Korean studies is required.It also calls for years of hard work without recognition. In short, itrequires a sense of mission.

This may sound like ivory tower idealism but Choi believes thereare people “like salt, like flowers hidden in the mountains” who areworking hard in their given places. “We need to bring those peopleto the light,” he says. As with Choi’s motto “Without notice, withouta name,” recognition would be welcome if it comes, but it cantake a long time. Choi was happy to wait. “I’m like [the ancient Chinesestatesman] Jiang Taigong, who spent his years in exile fishingwithout a hook, waiting for someone to come for him,” he says. Hespeaks of a time frame of a thousand years, no less. If recognitiondoesn’t come in this lifetime, then perhaps in posterity.

Fortunately, Choi’s wait was far shorter than a thousand years.In addition to acclaim for his work overseas, in September this yearhe was named one of six winners of the National Academy of SciencesAwards. He sees the award as recognition of translation asan academic field of study in its own right. His wife, who was invitedto stand on the podium with him when he received the award, ispleased that his quiet effort over the past decades has been noticed.The same for his daughters in the United States, who had sent him aKindle to comfortably carry around the vast collection of books thathe needs in his work. He doesn’t like leaving home without it.