Director Lee Joon-ik has certainly enjoyed his share of commercial success, from his recordbreakinghit “King and the Clown” (2005) to more recent releases like “The Throne” (2015).But it’s clear that his passion for filmmaking extends far beyond box office revenues. Throughout his career,Lee has thought long and hard about the kind of stories he wants to tell, thereby contributingto the cultural discourse taking place in Korean society.

Lee Joon-ik has made 11 movies since his debut in 1993. The posters decorating the wall behind his desk at his office give a condensed view of his career. From left are the posters for “The Throne” (2015), “Dong-ju: The Portrait of a Poet” (2016), “King and the Clown” (2005), “Radio Star”(2006), and “Hope” (2013).

In early 2016, Lee Joon-ik’s film “Dong-ju: The Portrait of a Poet” enjoyed a very special kind of success. An independent feature with a budget of only 500 million won ($440,000), this biographical film about one of Korea’s best-loved poets, Yun Dong-ju (1917–1945), was rapturously received by critics and audiences alike. Shot in black-and-white, it explores Yun’s coming of age during one of the darkest eras in Korean history. It is both an unflinching look at his tragic death after being arrested in Japan as a “thought criminal” toward the end of the colonial era, and a celebration of his sad but beautiful poems, which appear interspersed throughout the film.

Thanks to word of mouth, “Dong-ju” remained in theaters for an unusually long release for a low-budget, independent production and ultimately sold more than 1.1 million tickets. The film has also received some international exposure, opening in the United States in a targeted release this spring, and also screening at the New York Asian Film Festival. A theatrical release in Japan, where the poet has a significant number of fans, is scheduled for the fall. We caught up with director Lee Joon-ik at his office in Chungmu-ro, the Seoul district that in decades past served as the hub of the Korean film industry.

Historical Fiction and Hollywood Techniques

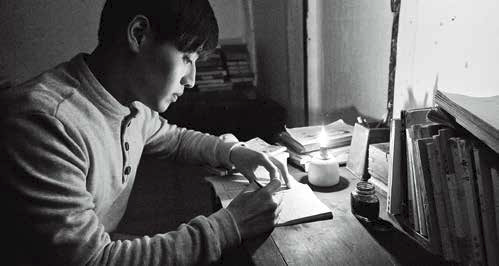

A scene from “Dong-ju: The Portrait of a Poet.” Lee Joon-ik says he chose to work in blackand- white to depict Yun Dong-ju as simply and honestly as possible, true to the shortlived poet’s image in the black-and-white photos that he was familiar with.

Darcy PaquetFrom your filmography, you seem to have a strong interest in history. Whatattracts you to films set in the past?

Lee Joon-ik I grew up watching a lot of Hollywood films, and saw a lot of Japanese classicsin my youth. People learn about European history both through European films and Hollywoodfilms. But while working in the film import business I realized that people from other countriesknew very little about Korea. They knew about Japan, and China, and their particular histories.But they had never seen any cultural products that might spark an interest in Korea. So onething that inspired me to make films was to fill that gap, and explore the question of what makesKorea different from China or Japan.

That’s how I ended up making “Once Upon a Time in a Battlefield” (Hwangsanbeol) in 2003.

People are familiar with the Crusades in Europe, but actually the seventh-century war depictedin this film, between the Silla, Baekje and Goguryeo kingdoms, was on a similar scale. During 30years of fighting, over 130,000 troops sailed in from China to take part. If I were shooting the filmnow I could probably do it on a much bigger scale, but at the time we decided to use comedy toappeal to viewers, and it ended up working quite well.

Still, the humor and content of that film was very local, with the dialects and all, so after thatI decided to explore something more universal, and that resulted in “King and the Clown.” Therewas a play that formed the basic source material, but I spent a lot of time researching the conceptof the clown. There’s the Pierrot in commedia dell’arte (comedy of craft), and clowns alsoappear in Shakespeare or in Tarkovsky’s film “Andrei Rublev.” I spent a lot of time thinking aboutthe differences between clowns in Europe and those of the Joseon Dynasty. Ultimately, I thinkmore than just being a foil or a vehicle for expressing an author’s thoughts, clowns in Joseonculture represent the masses in some way. They strongly assert their own point of view, andtheir relationship with powerful figures like the king is more tense. I shot the film with this conceptin mind, and it was a success not only in Korea, but also seemed to connect with internationalaudiences.

DPI agree with you that Korean culture has its own distinctive qualities that clearly differfrom those of Japan or China, but where do you think that uniqueness comes from?

LJ Throughout its history, Korea had diverse influences from its neighbors. Until the earlypart of the 19th century, China had a tremendous influence, then from around 1900 it was Japanthat influenced the country. Following independence from Japan’s colonial rule and the KoreanWar, the United States exerted predominant influence. So you have these cultural influencesfrom three major empires all mixed up together. Besides, artistic creators tend to draw the mostenergy from strong emotions. Because of their tough history, the Korean people have had a wellspring of hardship, pain, and anger inside of them.

In terms of film production, the United States, Japan, and Chinahave often drawn on literature and novels, but in Korean culturethere are fewer fictional stories to adapt. That is why Korean filmmakershave been pushed to develop original stories. Often theydo that by combining the emotions contained in their difficult pastwith the filmmaking techniques of Hollywood, which has resulted insomething new.

A Low-budget, Black-and-White Film

DPWhat was the starting point for the film “Dong-ju: The Portraitof a Poet?”

LJ Actually, in the late 1990s I produced a film called “The Anarchists,”which was set in Shanghai during the colonial era. Thescreenplay was written by Park Chan-wook, and while we wereresearching and preparing the film, I thought a lot about how toreconstruct this period on the big screen. Ultimately the film wasn’ta success, and I moved on to other projects.Then in 2011, I was invited to a film festival in Kyoto which wasdevoted to historical films. I screened my films “Battlefield Heroes”(Pyeongyangseong) and “Blades of Blood” (Gureumeul boseonandal cheoreom), and while I was there, I decided to visit DoshishaUniversity, the last school that Yun Dong-ju attended. We went tosee the poetic tablets that were erected to him, and we also walkedalong the bridge that appears in Jeong Ji-yong’s poem “Apcheon”(Kamogawa).

A couple of years later, on the way home from a Directors’ Guildworkshop in Jecheon, I happened to sit next to director Shin Yeonshickon the train. He’s a specialist in low-budget films, whereas Ihad only shot commercial films. I told him I’d been thinking aboutmaking a film about Yun Dong-ju, but that it wouldn’t be possible todo as a commercial feature. It costs a lot of money to re thathistorical period, and investors won’t finance it if they think it won’trecover its budget. I asked if he’d be able to write a script that couldbe shot on a low budget. He was excited about the idea, so I askedhim to aim for a budget of 250 million won($220,000), and proposed centering thedrama around Yun’s relationship with hiscousin Song Mong-gyu. That’s how it started.

DPHow would you introduce the poetYun Dong-ju to people from other countrieswho aren’t familiar with him?

LJ Actually his work has been translatedand published in several languages, but he’snot internationally famous, so few peoplewill have come across his poems. In general,there are very few Korean poets who areknown abroad, except Ko Un perhaps. YunDong-ju’s poetry itself is quite important,but his life and death are no less importantto remember.

The colonization of Korea by Japan is notwell known outside of Asia. But I think thedeath of poet Yun Dong-ju in Fukuoka Prison,after undergoing medical experimentation,is something that belongs not just inKorean history, but in world history. Therewas an instigator of this experimentationnamed Shiro Ishii, the surgeon general whod Unit 731 in the Kwantung Army andexperimented on 200,000 people in Manchuria.He was responsible for the medicalexperiments in Fukuoka Prison that were performed on 1,800people, including Yun Dong-ju and Song Mong-gyu. It’s obvious thatShiro Ishii should have been tried for war crimes, like those responsiblefor Nazi medical experiments, but he lived out a comfortablelife and died of old age in his 90s. This film is not just the story of apoet, it is about the conscience of a certain historical era.

DPWhat do the two real-life protagonists of this film, Yun Dongjuand Song Mong-gyu, share in common, and how are they different?

LJ They were born in the same place, and died in the sameplace. They were cousins, close friends, and competitors. YunDong-ju’s poetry did not emerge simply from sitting alone in a roomand writing. We can also feel in his s the influence of thepeople who most influenced him psychologically and emotionally.More than anything, it was the historical era in which he lived thataffected him most. But we may argue that after leaving home andembarking on their journeys, it was Song Mong-gyu, the personclosest to him, who left the greatest influence on his work.

A poet expresses the pain of a particular era. But that pain wasalso reflected in their friendship: in feelings of inferiority, or antagonism,or at times, in the sense that each person was a mirror of theother.

“The colonization of Korea by Japan is not well known outside of Asia. But I think the death of poet YunDong-ju in Fukuoka Prison, after undergoing medical experimentation, is something that belongs notjust in Korean history, but in world history.”

Looking Back at Modernity

DPThese days there are quite a number of Korean films set inthe colonial era. In the past, directors seemed to consciously avoidthat period, and there were very few films that garnered commercialsuccess. What has changed, in your opinion?

LJ Yes, in the past the colonial era was largely passed over byfilmmakers. The reason is because it was an era of despair. Whenviewers spend money to go to the theater, they want to experience asense of triumph.

In times when Korea was struggling and life was tough, tellingstories about failure was unwelcome. But economically, Korea hasgrown a great deal, and I think perhaps now we can more confidentlytell stories about our past failures. A good example is ChoiDong-hoon’s film “Assassination.” The film is set in the dark days inour history, but the story also emphasizes personal triumphs, suchas when Jun Ji-hyun’s character succeeds in her mission. I thinkthat enabled the film to be successful, and in a way it opened upthree decades of potential stories for Korean filmmakers.

DPWhat are you working on these days? Do you have anotherfilm project under way?

LJ I’m developing two or three screenplays, but I’ve chosensome tough subjects to tackle, so it’s a bit of a challenge right now.What I’d most like to make is a film that pursues the issue of Koreanmodernity. In the case of the United States or Japan, the introductionof modernity was fairly straightforward. But in Korea it’squite complicated. How it’s usually explained in terms of world historyis that Japan colonized Korea and introduced modernity. I thinkthere are problems with that narrative.

Personally, I think we can locate the start of modernity in theencounter of late Joseon-era society with Catholicism. It touchedoff a movement called “Seohak” (literally, “Western Learning”) tointroduce Western thinking and science to Korean society. Eventuallythis was counterbalanced by the “Donghak” (“Eastern Learning”)movement, and in many ways the conflict between the twomovements led to Japan’s colonization of Korea.

I think a film that explores the growth of Seohak and then Donghak,leading to Korea’s loss of national sovereignty, could say somethinginteresting about the nature of modernity in Korea. But perhapsI’m being too ambitious. Discussing all this in a single screenplayis a huge task!

Lee Joon-ik (third from left) chats with the actors during the shooting of “Dong-ju.”