Do Ho Suh, one of the most prominent figures in contemporary Korean art, is best known for fabric installations that recreate the façades of the homes he has lived in. Moving fluidly across sculpture, drawing, and video, he explores themes of home, physical space, emotional transference, memory, individuality, and collectivity.

Do Ho Suh, “Rubbing/Loving Project: Seoul Home,” 2013-2022. Installation view, The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh: Walk the House. Courtesy of the Artist, Lehmann Maupin New York, Seoul and London and Victoria Miro. Repurposing supported by Genesis

© Do Ho Suh. Photo

© Tate (Jai Monaghan)

What is a “home”? The work of installation artist Do Ho Suh begins with this deceptively simple yet fundamental question. After majoring in traditional Korean painting, he left for the United States in the early 1990s, a sojourn that turned into a wayfaring life. Various countries, including Germany and England, became the base for his work. Each stop was more than a change of address; it was a shift in perception and mode of existence. Thus, for Suh, a home became a vessel that stored an identity and a stage to explore cultural collisions and boundaries.

RECREATING MEMORY

Suh treats the concept of “home” as if it were a sculpture. Yet his homes are not fixed, solid forms but rather fluid, living presences. One of Suh’s early works, “Seoul Home/L.A. Home” (1999), is a meticulous recreation of the traditional hanok in Seoul where he lived. What is particularly striking about the recreation of this childhood home is its portability. Rendered in pale jade-green hanbok fabric, the art work can be folded and reassembled for display. Its title also changes depending on each exhibition venue, a list that already includes New York, Baltimore, London, and Seattle. The light, air, and time of each location adds a new layer of meaning to the house. Ultimately, the installation suggests memories of home can be endlessly translated and recreated. This reflects Suh’s unique methodology for exploring the complex relationship between place and identity, as well as the foundation of his nomadic life.

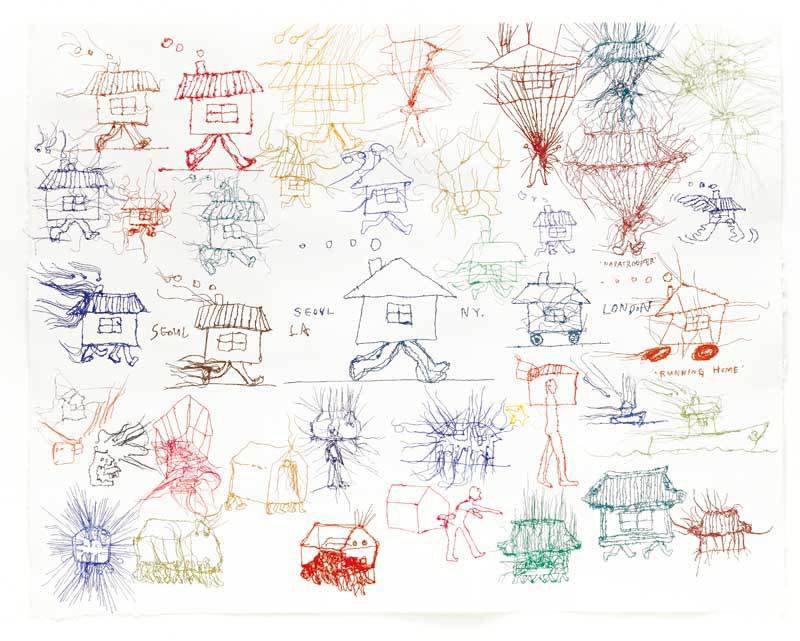

Do Ho Suh, “My Homes.” 2010. Courtesy of the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul and London, Victoria Miro and STPI - Creative Workshop & Gallery © Do Ho Suh

Photo by Hyunsoo Kim

This trajectory has extended beyond museum walls into public space. “Bridging Home, London,” installed near Liverpool Street Station in 2018, featured a hanok and bamboo garden that had seemingly fallen onto an overpass. By visualizing the tension arising from the meeting of unfamiliar cultures and environments, Suh gave intuitive form to the opposites he experienced while living abroad — tradition and modernity, East and West. The image of a home that has crashed onto unfamiliar territory has since reappeared in later works, becoming a metaphor of how migrants today may see themselves. In this way, Suh does not stop at mining his own memory; he uses “home” to bridge cultural divides.

Do Ho Suh, “Nest/s.” 2024. Installation view, The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh: Walk the House Courtesy of the Artist, Lehmann Maupin New York, Seoul and London and Victoria Miro. Creation supported by Genesis © Do Ho Suh. Photo © Tate (Sonal Bakrania)

ACTION AND EMOTION

At his solo exhibition Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, running at Tate Modern in London until October 26, this perspective unfolds with even greater clarity. The title comes from a phrase used by Korean master carpenters (daemokjang) when dismantling a traditional house and taking it to a new location — a practice deeply connected with Suh’s childhood experiences, as seen in his earlier works. Suh’s father, the renowned master of ink-wash abstraction Se Ok Suh, built and lived in a hanok in Seoul’s Seongbuk-dong. Modeled after a building in Changdeok Palace and constructed in collaboration with a master carpenter, this house naturally became a place firmly grounded in Do Ho Suh’s memories.

The concept of a “walking house” extends beyond visual representation to a form of tactile recording. In his large-scale installation “Rubbing/Loving: Seoul Home” (2013–2022), Suh traced the surfaces of his former home in Seongbuk-dong, transferring the accumulated textures of memory onto paper. He wrapped the hanok’s exterior walls in traditional paper (hanji) and rubbed graphite over them, slowly revealing their texture and structure. This process of reviving the emotional bond between artist and place is embedded in the work’s title, a play on the Korean pronunciation that layers the meanings of “rubbing” and “loving,” invoking action and emotion side by side.

As the artist noted in an interview with The Guardian, “One space can often carry the memory of other spaces.” This belief — that a physical place stores past life and sensation, and that these can be relocated — finds expression in “Nest/s” (2024), placed at the heart of the Tate Modern exhibition. This installation stitches together, in thin fabric, the floor plans of rooms that Suh has inhabited around the world, coming to life through the movement of visitors. Walking through its passages, where boundaries between inside and outside dissolve, viewers pass through a distant moment in time.

A similar approach shapes “Perfect Home: London, Horsham, New York, Berlin, Providence, Seoul” (2024), which uses the artist’s current home in London as its framework and layers it with spatial layouts of previous homes. The positions of small objects such as light switches and faucets faithfully follow their actual heights and locations, while colors serve as visual markers dividing the memories of each city. As with “Nest/s,” visitors walk through the installation, retracing each detail as if slowly turning the pages of a diary, quietly following the trajectory of a family’s life.

Do Ho Suh poses in his London studio. An installation artist working across New York, London, and Korea, he is considered one of the most influential voices in contemporary art. His practice transcends the fixed notion of space, probing instead a nomadic understanding that traverses temporal and spatial boundaries.

© Gautier Deblonde, DACS 2025

HOME, AGAIN

Now we return to the original question: What does “home” mean to Do Ho Suh? Over a journey that has crossed national borders, the artist has sought new possibilities by dismantling the familiar home and placing it anew in foreign soil. His houses, made of thread, fabric, and paper, always begin from personal experience, yet they hold within them the era, the world, and the moments of movement itself. Amid repeated relocations, the act of recreating his own home is a ritual allowing the artist to remember places and shuttle between past and present. Each work, endlessly folded and relocated without being fixed in one place, prompts us to reconsider the meaning of home today. Perhaps home is not an anchored place, but a long journey to be continually explored. If so, then where will the place we now stand, laden with its own stories, lead us next?

Do Ho Suh, “Perfect Home: London, Horsham, New York, Berlin, Providence, Seoul” (detail). 2024. Polyester, stainless steel. 455 x 575 x 1237 cm. Courtesy of the Artist, Lehmann Maupin New York, Seoul and London and Victoria Miro.

Photo by Jeon Taeg Su © Do Ho Suh

Do Ho Suh, “Home within Home.” 2019. Polyester fabric, stainless steel. 744 x 827 x 805 cm. Installation view, Incheon International Airport, Seoul, Korea. 2020.

© Do Ho Suh. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London.

Photo by Jeon Taeg Su