It is not easy to live a life of service and self-sacrifice for others. It must be even harder to do so in a faraway land. Robert John Brennan, a.k.a. Ahn Kwang-hun, made a difficult decision over a half century ago. Now, as “a friend of the poor,” the New Zealand-born Catholic father finds Korea a lot more comfortable than his homeland.

Barely five minutes had passed before an English interview turned into a Korean conversation — unwittingly. Little wonder. Since he first set foot in Korea 53 years ago, Father Robert John Brennan has lived as a friend of Koreans, especially the poor and powerless, speaking their language.

He currently serves as the CEO of the Samyang Citizens’ Network. It is a mutual aid community organization that provides vocational, educational and housing support to residents in Samyang-dong, a humble neighborhood in Gangbuk District, northern Seoul. As its name Gangbuk (“north of the river”) implies, it is an old district, a sharp contrast with Gangnam (“south of the river”), which symbolizes Seoul’s wealth and cutting-edge trends, as showcased in Psy’s global hit song, “Gangnam Style.”

Community Mutual Assistance

The New Zealand-born Catholic priest Robert John Brennan arrived in Korea in 1966 and has since lived in this country, helping the disadvantaged. Among Koreans, he is known as “Father Ahn Kwang-hun, Friend of the Poor.”

Samyang-dong is one of the poorest areas even in Gangbuk. Last summer, Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon chose the neighborhood for his month-long “experience-the-poor” sojourn. Upon moving into a rooftop room, Park paid a courtesy call on Father Brennan, a Samyang-dong resident since 1992, when he became the first provost of a new parish church on the recommendation of the late Cardinal Stephen Kim Sou-hwan.

“When I first arrived, shanty houses covering a hill caught my eye,” recalled Father Brennan. “I could see forced demolition would start here, too.”

His first chore was to rent a home. Three years later, redevelopers began to tear down houses in the area. Father Brennan’s house served as the residents’ gathering site to discuss countermeasures. “There were many things to do, including the education of residents about their rights and finding them temporary shelters,” he said.

Next came the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98, leaving legions of people jobless. To help them, he conducted projects jointly with the House of Sharing, a charitable organization run by the Anglican Church of Korea, providing job counseling services and operating a housing welfare center and microcredit programs.

Thus began the Samyang Citizens’ Network. “The key laid in encouraging residents to unite, form a community and make a living,” Brennan said. “Now the common problems of redevelopment projects, such as kicking out tenants by employing hoodlums to threaten them, have declined and welfare has improved.” But he said many tasks remain. These days, the focus is placed on smaller activities more closely related to daily life. “We send helpers to mothers who have recently given birth, offer housekeeping services and link student volunteers to night schools,” he explained.

A Priest of Slums

The New Zealand-born Catholic priest Robert John Brennan arrived in Korea in 1966 and has since lived in this country, helping the disadvantaged. Among Koreans, he is known as “Father Ahn Kwang-hun, Friend of the Poor.” © News Bank

Brennan’s struggle for evictees and squatters began in Mok-dong, western Seoul, in the 1980s. “With the 1988 Seoul Olympics approaching, the city was being cleaned and beautified,” he said. “At the time, the neighborhood of Mok-dong, located along the road from Gimpo International Airport to downtown Seoul, was dotted with shabby houses. It was an eyesore for the authorities.”

Brennan joined residents targeted for eviction and relocation to oppose officials, redevelopers and their hired thugs. “They beat even old people and children while the police stood by with their arms crossed,” he said.

Brennan’s ties with the then residents of Mok-dong have continued until today in many beautiful ways. He officiated the weddings of young people who had fought alongside him. They are now middle-aged couples and their children have reached their age at the time of the Seoul Olympics.

“As they call me father, their children call me grandfather. I’m happy when they call me grandpa,” he said. One of those families invites him every weekend, and as any grandfather would, he enjoys spending time with his “children” and “grandchildren.”

An unforgettable episode transpired. There was a sick poor man barely subsisting in Samyang-dong. Brennan sent volunteers to look after him in various ways. “After a few months, the man made a tearful confession that he was one of the hoodlums who had harassed evictees in Mok-dong,” Brennan said. “He repented and asked for forgiveness, saying thanks for taking care of him.”

“I hope Korea will become a more humane society in which young people are considerate about older ones, wealthy people are concerned about poor ones, and learned people try to understand the less educated better.”

Guiding Spirit

Recalling that “Cardinal Stephen Kim always worried about weak and suffering people, stood by them and tried to keep their dignity,” Father Brennan said there must have been a reason for the cardinal to send him to two of the most deprived districts in the capital.

“Church for the sake of church is the last thing I want to see,” Brennan said. “The church should not tell people to come but walk toward them.”

This is the very spirit which has guided Father Brennan ever since he started his service in Korea in 1968. His first stint was in the coal mining town of Jeongseon, in the mountainous province of Gangwon, where there were not even hospitals to provide proper medical care to the miners and their families. He played a pivotal role in establishing the St. Francisco Hospital there. He served in Jeongseon and the nearby port of Samcheok until 1979.

The 11-year service in Gangwon was followed by a sabbatical year at the University of California, Berkeley where he studied theology. He returned to Korea and Cardinal Stephen Kim appointed him to Mok-dong.

Robert John Brennan was born in Auckland, New Zealand, in 1941. The first boy among five children born to a devout Catholic family, he was smart and sincere. His parents held him to high expectations and hoped he would have a secular occupation.

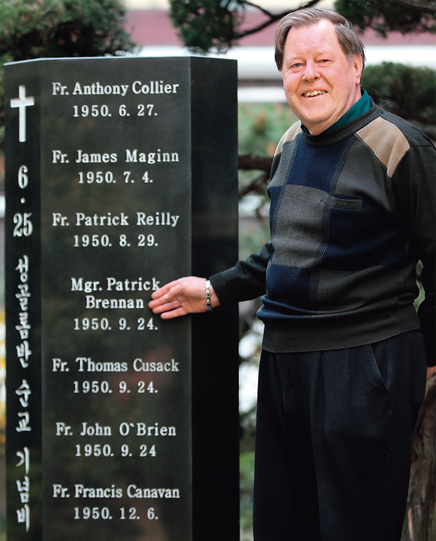

However, the young Brennan was moved by a church newsletter his mother received periodically. He was especially drawn to articles about New Zealand’s Catholic priests who began serving in Korea in 1933, when it was a colony of Japan. Then, during the Korean War of 1950–53, seven priests were martyred. “I found one of those priests had the same family name as mine,” he said. “Then I made up my mind.”

Brennan took enormous pains to persuade his parents to enter the Columban Mission Society, a seminary in Sydney, Australia, in 1959. After six years of study there, he became an ordained priest in 1965. The following year he was appointed to serve in Korea.

He spent his first two years in Korea learning about the country, including its language. He studied at the now closed Myongdo Language Institute in Jeong-dong, operated by Franciscan fathers. There he befriended Seoul National University students, who renamed him Ahn Kwang-hun.

“They told me the Chinese characters of my first name Kwang-hun mean ‘spread and preach light,’” said Brennan. Among Koreans, he has long been known by his Korean name rather than his birth name.

Social Engagement

Father Brennan poses with local residents in front of the office of the Samyang Citizens’ Network.He is CEO of the community organization established to provide vocational training and help resolve housing problems in Samyang-dong, a deprived neighborhood in northern Seoul. © Asan Foundation for Arts and Culture

In 1969, he met the late Bishop Daniel Chi Hak-soon in Wonju. Bishop Chi was widely known for his love of and sacrifices for the weak and disadvantaged. He was also respected for his struggle against the dictatorship of Park Chung-hee. From their first meeting onward, Bishop Chi deeply moved Brennan. He still remains Brennan’s role model for his activities inside and outside of church.

“I am officially retired, but I still give sermons from time to time. And people who hear my sermon for the first time may think I am a socialist of sorts, reminding them of liberation theology,” said Brennan, chuckling.

“I always try to stand on the side of the poor and oppressed, and emphasize social issues. I do not intend to politically influence people. Instead, I try to lead them to make the right choices in elections, asking them to listen to their conscience and consider what will benefit the entire nation rather than what they can get as individuals.”

Brennan said he had much to say about the Korean government’s urban redevelopment policy. “Redevelopment should be planned for residents living in the neighborhood, but unfortunately, most current projects are driving them away to build expensive apartments for wealthy people from other areas,” he said. “Good redevelopment projects should rehabilitate declining regions and improve the lives of local residents.”

He also stressed the need to rebuild narrow alleys bulging with stairways in ways to allow older citizens to move around more freely.

As a senior himself, Brennan said he feels unsettled when young people do not offer their seats to elders in subways and buses. “When I first came to Korea in the 1960s, the country was poor but people cared more about others, and young people were more respectful to elders,” he said.

“Now Korea has become rich and powerful, but Korean society has become cold-hearted. I hope Korea will become a more humane society in which young people are considerate about older ones, wealthy people are concerned about poor ones, and learned people try to understand the less educated better.”

“Koreans are tough in good ways,” he said. “They fight to the end to accomplish their goals, as seen in their struggle for liberation from Japanese rule. At the same time, they are ready to share what they have with others, although such generosity has considerably diminished since people began to live in apartments.”

Permanent Home

Father Brennan said he has never regretted his decision to serve in Korea. From time to time, he goes to New Zealand where his brothers and sisters and their children welcome him. However, since his mother passed away several years ago, he has traveled less frequently.

A few years ago, on his third attempt, Brennan obtained permanent residency. “It was not easy because all that I have done in Korea is work for the church and live with Koreans,” he said, jokingly. “But I don’t want to leave. I have even prepared a place here to lie down after dying,” he said.