Master craftsman Jo Dae-yong’s family has made bamboo screens for five generations, beginning in the mid-19th century during the Joseon Dynasty. In traditional Korean houses, bamboo screens were not only practical household items used to divide space, adjust light and protect privacy, but also beautiful s of art with the family’s values and wishes woven into the decorative designs. Completed over 100 days with tens of thousands of painstaking touches, the process of weaving a fine bamboo screen is akin to spiritual discipline.

On the weaving loom, a small weight is attached at the end of each thread. To make a screen, fine bamboo strips trimmed to a 1mm width are woven with silk threads, its decorative patterns d by intricate manipulation of the threads. For complicated designs, more than 500 spool weights are needed.

Whenever Jo Dae-yong recalls his father, he thinks of his hands that never stopped moving. His father used to weave fishing nets in the seaside village of Tongyeong on the southern coast of Korea. The nets he designed and weaved always worked well, regardless of whether the wind was northerly or westerly. As the winter deepened, he used his deft hands to cut the bamboo growing around the village, strengthened by the sea breeze. He would split the stalks into thin strips and weave them together to make a screen as tall as a grown man.

Once the bamboo screen left his father’s hands, it would end up hanging in the doorway at the home of one of his neighbors. Natural screens could be made with different materials, including reeds and hemp stalks, but his father used nothing but bamboo.

Jo Dae-yong explained that in the old days, screens were an indispensable part of everyday life: “You know the old saying, ‘Boys and girls should not sit together after the age of seven’? Gender segregation was such that the women’s quarters were seldom visited by outsiders. The doors to their rooms, when opened during the warm seasons, were covered with screens to hide them from view. A bamboo screen hanging in the doorway looks translucent from the inside, letting those inside see what goes on outside, while it looks opaque from the outside, thus protecting their privacy. This is due to the difference in brightness between the two sides. The screen also allows air to circulate while softening the harsh light filtering through it.”

Separating the inside from the outside and distracting people’s eyes away from private spaces, natural woven screens were an ingenious means of managing the living environment. The use of woven screens dates back a thousand years to the Three Kingdoms period. In the palace, a screen placed in front of the throne prevented the subjects from the impropriety of laying eyes on the sovereign’s face. Screens were also used to separate the sacred from the secular realm at ritual venues, such as the spirit tablet chamber at an ancestral shrine. Small screens hung on the doors and windows of a palanquin concealed the person inside from view.

As soft afternoon sunlight shines in, and the screen is stirred by the breeze caressing its surface, the woven designs are gently fused into the landscape beyond it.

Gathering of Bamboo Canes

Jo Dae-yong took on his father’s craft as his calling. He used to hover around his father when he wove bamboo strips into screens. There was no real beginning or end to his apprenticeship; he had been neither eager nor unwilling to learn the craft. At first, he would just casually watch his father’s hands operating the weaving loom. In time, however, he came to use the loom as if it had always been his. For years, his days were filled with the same routine: working at the loom for hours on end, kicking the loom away and lying on the floor exhausted, then sitting up again, pulling it into place with his feet to resume weaving.

That was how his father had spent his days, too, as so had his grandfather and his great-grandfather. “My great-grandfather, who had passed the exams for military officialdom in 1856 and was waiting for his appointment, wove a bamboo shade to pass the time and offered it to King Cheoljong. They say the king was delighted by the gift,” Jo said. “Both my grandfather and my father had other occupations. They wove screens in their leisure hours and would either give them away or sell them to earn money on the side. My father started weaving full-time after retirement, and I was helping him prepare a work to be submitted in a contest when I decided to pursue it as my career. That was in the mid-1970s.”

What did it mean for the men in Jo’s family to carry on a craft that was not an occupation through generations? What was inherited - a life, a culture, or a skill? How can one describe in words the legacy of an ancient handicraft passed down from one generation to another as the feelings in one’s hands or the motions they make? What did it mean to Jo Dae-yong, the country’s most renowned weaver of bamboo screens and holder of the government-designated title, Important Intangible Cultural Property No. 114? One question led to another as his story went on.

The master artisan began to delve into the specifics of his work: “Wood for building a house is gathered before the sap starts to rise in the trees. The same is true for bamboo. It should be cut in dormancy before spring comes. Bamboo stalks cut in summer are apt to break with the lightest touch. Bamboo doesn’t snap so easily, except when insects bore holes in the culm. So, we would boil summer bamboo with lye to prevent insect infestation.”

The quality of a product is determined by the quality of the raw materials. Knowing this, Jo has been especially fastidious about choosing the right bamboo, namely haejangjuk (Arundinaria simonii).

“Wangdae (Phyllostachys bambusoides), also known as ‘giant timber bamboo,’ is thick and the surface is sleek with hardly any scratches because it grows sparsely,” Jo explained. “So it is neat and clean when skinned and woven, but because it is hard it is also easily broken. On the contrary, haejangjuk is slender and grows in dense clumps. When a storm blows, the swaying canes lash each other leaving scratches on the stems. But they are soft, pliable and less prone to breaking. You know the thin bamboo stems used in the old days to make bows and tobacco pipes? That’s what I’m talking about.”

As he spoke, Jo pointed at a stack of bamboo strips in the corner of his workshop - his raw materials for the year, collected from last December to January. He said it should be enough to make seven or eight screens. To obtain the strips, he has to crouch on the ground and read the past life of the plant. He pushes his way through the dense bamboo groves, looking for straight stalks with fewer scratches on the surface. Saplings in their first or second year are unsuitable because they are pulpy and difficult to cleave. Only the three-year-old canes that split down the length with a gentle push of the knife can satisfy him. But only one out of ten stalks he examines meets this condition.

Jo Dae-yong’s family has made bamboo screens for five generations, beginning in the mid-19th century. His daughter, Jo Suk-mi, works with her father at the loom.

An Artwork and Household Item

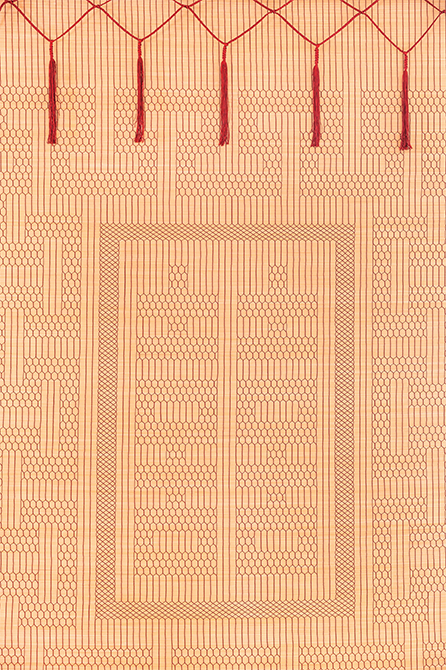

“Bamboo Screen with Character Meaning Double Happiness and Tortoise Shell Design” by Jo Dae-yong, 2017, 180 x 132 cm. The screen has an ideogram d by joining two of the same Chinese character meaning “happiness,” and decorating them with a tortoise shell design.

The hard work has taken a toll on Jo’s health. “After spending a month gathering the culms in the groves, I always suffer from back pain,” he said. “The doctors warned me not to sit on the floor for too long. But it’s harder not to do so, as I’ve spent my entire life sitting on the floor weaving at the loom.”

Collecting the culms is only the beginning. The next step is to cut them to the size of the shade to be made, usually 125-180 cm wide and 180 cm high, removing the skin and scraping out the inside before they darken. The culms are split into long strips and dried for a month, exposed to sunlight, wind and morning dew. When the green surface turns ivory, they are cut again into 1mm-thick strips. Then comes the trickiest part - trimming the strips by passing them through a hole on a steel plate, called gomusoe.

Jo described the painstaking procedure: “You strike a thin metal plate with a nail, creating a sharp protrusion on the other side. Then, you rub the tip with a whetstone, making a tiny hole. Each one of the 1mm-thick bamboo strips is passed through the hole. The sharp rim of the hole shaves the strip thinner. I do this three times. Each strip becomes about 0.6-0.7 mm thick. I have to keep my hand extremely steady while pushing or pulling the strip through the hole because tilting it slightly would end up breaking it. Doing this over and over again, your fingertips get worn down and riddled with splinters. A keen sense of touch is crucial to the job, so you can’t wear gloves, however thin they may be.”

Given that some 1,800 strips are needed to make one screen, and that each has to be passed through such a hole three times, plus an extra 100 strips against losses, this procedure has to be repeated 5,700 times. This means fine-tuning the movement of his arms and fixing his gaze to notice the slightest tilt as many as 5,700 times. However, Jo has never counted the number.

As to mastering this skill, he said, “You just keep doing it until you’re satisfied with the result. It takes at least five years just to get the hang of it, longer than any other procedure.”

It usually takes Jo around 100 days to complete a screen - 25 days preparing the strips and the other 75 days weaving them.

More than 1,800 bamboo strips are needed to make one screen. To obtain the material, Jo combs the bamboo fields of Tongyeong every year from December to January. He uses the species of bamboo called haejangjuk, because it is thin, pliable and less prone to breaking.

The finely trimmed strips are affixed to the loom and woven together with silk thread, creating decorative designs and characters along the way.

Since these adornments are added solely with the thread, the number of shuttles used may exceed 500 if the patterns are complicated. That is, the design is woven with 500 strands of thread.

“The designs are mostly ideograms expressing wishes for long life, good fortune, health and well-being. Look at the screen on the wall,” Jo said, asking, “Do you see the two identical letters juxtaposed at the center, meaning ‘double happiness’? Then, do you also see the hexagonal or fishnet patterns filling the space that forms each stroke?”

Hung on the wall like a scroll, the fine bamboo screen featured faint designs, recognizable only at close range.

They were simple and elegant, but hardly impressive at first glance. Things change, however, when the same screen is suspended across the doorway of a traditional Korean house. As soft afternoon sunlight shines in, and the screen is stirred by the breeze caressing its surface, the woven designs are gently fused into the landscape beyond it. The play of light and the wind, turning the screen translucent, brings the patterns into vivid relief, or fuses them into the view on the other side. Responding beautifully to changes in time and space, a bamboo screen straddles the boundary between an everydayand an artwork.

Changes in the Living Environment

“I don’t want to make the same screens year after year. The strips and the thread that I’ve used have become ever thinner over the years, but there’s a limit to how thin they can be,” Jo said. “Now, what makes the difference is the design. I’ve tried weaving ideograms into the screens in different styles, but with more characters - and more strokes in each character - it gets more complicated to fit the hexagons of woven thread evenly into the blank space in each stroke. Creating designs with thread may look simple, but it requires meticulous planning and execution. I have done this for over 50 years, but I’m still cautious.”

Speaking of designs, his accounts begin to reveal the shape of his character. When asked about the most elegant bamboo screen he had ever seen, Jo recalled, “I was once asked to repair a damaged screen that Francesca Rhee, wife of former president Syngman Rhee, had given to her husband’s family when she moved to the United States. I could have disassembled and restored the screen, but instead I advised the client who brought it to preserve it in its original form in honor of the person who had presented it. The client agreed. Later, I red its designs in another screen, which received the Presidential Award in the annual Korean Traditional Handicraft Art Exhibition.”

Jo’s recollections moved on to an unforgettable work that he came across at Songgwang Temple in Suncheon. It was a bamboo scroll for storing Buddhist scriptures, and the dozens of flying bat designs woven into it were exquisite. Talking at length about it, he apparently yearned tosuch a work of his own.

But when asked if this was so, he replied, “I feel intimidated, because the monk who made it must have devoted himself entirely to the work for a few years. I could tell, by looking at the scroll, how much of his heart and soul he put into it.”

For an artisan who is so cautious, even in his position as a “living human treasure,” reality is precarious. As traditional homes have disappeared, the demand for bamboo screens has also shrunk. For the master artisan, selling rather than producing has been the more pressing matter at hand for some time now. Furthermore, it is difficult to find a way to pass down his craft as hardly anyone regards it as a promising career. Although Jo’s son and daughter decided to succeed the family trade, the future of the craft seems uncertain.

With rain falling outside all through the interview, the artisan, who had repeatedly shifted in his seat to cope with his back pain, now lay prone on the floor, only lifting his head to answer questions. Up until six to seven years ago, he said, his workshop had visitors, including busloads of kindergarten children who came for a hands-on experience. Now, with no one visiting, the general lack of interest saddens him.

Obviously, into its fifth generation, an illustrious family tradition is flickering amid the harsh wind of time.