Movie directors who have accomplished the“miraculous” feat of earning both commercial successand recognition as “auteur” are no longer rare. Acclaimat a prestigious international film festival can serveas a springboard for the box office success of auteurdirectors in the domestic market. These powerfuldirectors are now dominating the Korean film scene.

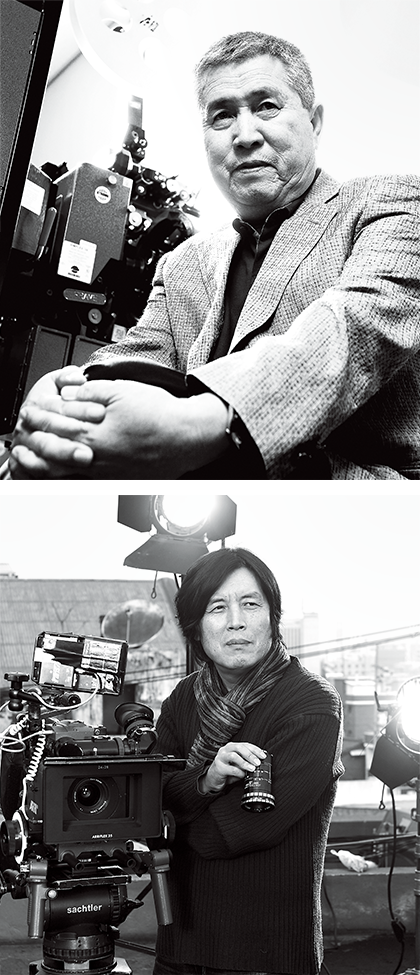

Veteran directors with 20-year careers, Hong Sang-soo (opposite)and Kim Ki-duk have delved into recurrent themes in their movies.

The director wields more power than anyoneelse on the film set in Korea. This canbe a risky generalization, since it’s not truefor every director. But still, many exert vast powerdespite the ever-increasing clout of media conglomeratesthat have vertically integrated film investmentwith distribution and screening. Noted directors withmegahits which have attracted more than 10 millionviewers are setting up their own production companies.Some place their wives in the CEO role whilethey write their own scripts and are actively involvedin the casting, editing, and post production. In otherwords, these star directors have acquired full controlof the entire filmmaking process.

In this sense, it can be said that “auteurism”describes almost all the currently active Koreandirectors. Here, we seek to chart the topography ofKorean film today by pairing big-name directors.

But still, many exert vast power despite theever-increasing clout of media conglomeratesthat have vertically integrated film investmentwith distribution and screening … In otherwords, these star directors have acquired fullcontrol of the entire filmmaking process.

Kim Ki-duk and Hong Sang-soo

Kim Ki-duk and Hong Sang-soo were both bornin 1960 and debuted in 1996. Kim made his debutwith “Crocodile” and Hong with “The Day a Pig Fellinto the Well,” which both generated a lot of buzz.They continued to release movies almost every year,which were generally well received at internationalfilm festivals. Both directors are known for thedistinct worldview that is infused in their movies,and although they haven’t enjoyed huge box officesuccess at home, their favorable reception abroadmeans that their fame and reputation are not likelyto wane anytime soon.

The premise of Kim’s movies is “sick capitalism.”They are known for blunt and explicit portrayalsof marginalized men stuck at the very bottomof the social ladder, who lead a brutish life ina distressed capitalist society. In “Pieta” (2012),Kim brings together all the cinematic elements ofhis past works and goes a step further. The movieis set in the dark alleyways and rundown shopsof Sewoon Shopping Center in Cheonggyecheon,downtown Seoul, once a symbol of industrializationbut now facing demolition. There, loan sharksresort to all manner of inhumane acts to get thepoor workers to pay up. The story centers arounda man who threatens, beats up, and extorts moneyfrom people; the extent of his cruelty makes himlook like an incarnation of evil, a monster spawned by a capitalistic society. But as the story develops, Kim has thecharacter look back on his life and repent, and even superimposesthe image of Christ’s sacrifice on him at the end of themovie.

Im Kwon-taek (opposite), master of the national realismgenre, and Lee Chang-dong, successor of the genre.

Hong Sang-soo closely adheres to similar themes and charactersin all of his films. This can be viewed either as a manifestationof auteurism, or his own mannerism. His movies exposemale-female relationships that are stripped of any romance orfantasy. His characters indulge in sensual relationships, usuallystarting with a drinking party and ending up at a motel, wherethe display and gratification of desires leave no room for loveto blossom. Hong reproduces the many faces of such desirethrough stylistic experimentation. His movie “Right Now, WrongThen,” which won the Golden Leopard at the 2015 LocarnoInternational Film Festival, features a movie director who meetsa young woman in Suwon, with whom he spends the day andends up getting drunk. The movie is split into parts one and two,each telling the same story but showing two different versionsof how things pan out. The juxtapositional structure gives uspause to ponder about life and art.Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-hoPark Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho take the genre film conventionsof Hollywood and adapt and indigenize them to fit theKorean situation, ingeniously telling the stories that they want.Hence, they are more popular than Kim Ki-duk or Hong Sangsoo.Park uses the mystery thriller genre to explore the recurringthemes of the burden of guilt and revenge, whereas BongKorean Cult ure & Arts 21shrewdly captures the structural contradictions ofKorean society. Another common feature is that,while on the surface their movies appear to followthe conventions of genre films, they are based oncreative, imaginative stories.

Widely perceived as a logical and intelligentdirector, probably more so than any other Koreanfilmmaker, interestingly, Park leans heavily towardthe sentiment of B-grade movies. But he sees themnot as low-quality flicks but a genre replete with asubversive imagination that is beyond the boundariesof A movies, with his artistic creativity makingup for time and budget constraints. Park’s “Oldboy”(2003) epitomizes his cinematic world. It is the storyof the oppressive burden of guilt and vengeancecontaining incestuous elements; the guilt of nothaving been able to protect one’s sister and the guiltof not having protected one’s wife and daughterspark vengeance, but when this falls through, it onlyleads to further irrational acts of revenge.

As for Bong, he has a knack for infusing grotesquehumor into his films, which often featureslow-witted characters thrown into an overwhelmingsituation that they just can’t handle. Whatmakes these stories intriguing is that as eventsunfold, the structural inconsistencies of Koreansociety are uncovered and laid bare. For example, in“Memories of Murder” (2003), which is based on thetrue story of an unresolved serial rape and murdercase in the late 1980s, Bong portrays the incompetenceof the police and their clumsy investigativemethods with elaborate attention to detail.

Im Kwon-taek and Lee Chang-dong

Im Kwon-taek and Lee Chang-dong deal withmore serious, weighty material in their movies.

Im debuted in the early 1960s and is still a prolificdirector with more than 100 movies to his credit.“Sopyonje” is one of his most notable works, whichbroke his own previous box office record when itwas released in 1993. The period movie’s themeof pansori (traditional Korean narrative song) andits adoption of a Western cinematic style garneredwidespread acclaim and attention.

Park Chan-wook (opposite) and Bong Joon-ho take thegenre film conventions of Hollywood and ingeniously adaptthem to the Korean situation to tell their own stories.

Lee is a writer-turned-movie director. Like hisrealist novels, his movies delve into unfortunateevents in modern Korean history or depict theweary lives of people today. Whereas Bong Joon-hotakes a direct approach in exposing the structuralinconsistencies of our society, Lee prefers to take a step back as if calmly contemplating the situation.Lee’s most noted work is “Poetry” (2010). It openswith a scene of children playing on a river bankwhen the body of a middle-school girl floats by. Themovie traces the events that led to her death andhow the fathers of the boys responsible for the incidentattempt to cover up the involvement of theirsons. Using poetry as a literary device, the death ofthe girl and the associated death of an old lady (whois the lead character) are given a deeper meaning.Na Hong-jin and Yeon Sang-hoAt the forefront of independent films and theKorean New Wave, which shows where Koreancinema is headed, are directors Na Hong-jin andYeon Sang-ho. Na has d his own distinctivecinematic world with a predilection for cruelty, andyet he is widely loved by the public. Teeming withviolence and gore, his movies show how a persondriven to the brink can turn into a cold-bloodedmonster. In “The Wailing” (2016), Na takes this toextremes: a series of mysterious deaths plaguing asecluded rural village; the arrival of a strange newcomershrouded in mystery and the spread of eerierumors; the inclusion of elements of the occult —an evil spirit from which there is no escape — andshamanism. With the placement of metaphors andforeshadowing throughout the movie, Na offersviewers hair-raising enjoyment.

Yeon scored a box office hit with his first liveactionfilm “Train to Busan” (2016), which drew over10 million viewers, but his animated films have notfared so well.

After “Train to Busan,” he went rightback to animation with “Seoul Station.” He has writtenand directed many short and feature-lengthanimated films geared toward adults that deal withcontroversial themes set in social institutions, suchas a school, the military, and religious organizations,delivering biting social commentary throughthe depiction of “monsters” that our society hasd.

It is interesting to note that the recent works ofboth Na and Yeon have featured invincible zombies.What is suggested by the fact that these KoreanNew Wave and indie directors have found hugecommercial success with their zombie flicks, a relativelynew genre in Korea? What does it say aboutour times?