Seonam Temple and Songgwang Temple, nestled on the eastern and western sides of Mt. Jogye in South Jeolla Province, represent major Korean Buddhist orders and are destinations of both tourists and followers of Buddhism. The mountain path connecting them is no less an attraction for hikers and believers.

A path about 6.5 km long on Gulmokjae, the hill between Seonam Temple on the eastern side of Mt. Jogye and Songgwang Temple on the western side, was naturally made by monks of the two temples walking back and forth more than 1,000 years ago. These days it is a hiking trail that attracts tens of thousands of visitors annually.

Spirit poles, called jangseung, stand on the Gulmokjae hill path. As village guardian deities, spirit poles are usually found at village entrances, but sometimes along roadsides as well to serve as guideposts.

When either “Songgwang Temple” or “Seonam Temple” is entered into Korean internet search engines, the first autocomplete suggestion is the path between them. Countless previous searches have obviously included the treasured 6.5-kilometer route as often as the revered destinations themselves in the far southern reaches of the Korean peninsula.

The temples occupy opposite sides of Mt. Jogye. In Korea, it isn’t uncommon for two ancient Buddhist temples of similar scale to be positioned in the foothills of a large mountain. But it is very rare to find such a pair made out of wood that are still standing today. The hot, humid winds blowing from the southern sea nurtured an array of broadleaf and pine trees to supply the timber for construction more than 1,000 years ago, and modern-day restoration projects have smoothed out damage by man and nature.

Opposite Slopes

Seonam Temple on the eastern slope of Mt. Jogye is closer to the summit, but the road between the temples covers an equal share of their side of the mountain. When public bus service was sporadic, the residents of Oesong (”Outer Pine”) Village at the entrance of Songgwang Temple used the path as a shortcut to the city of Suncheon. But these days, bus No. 111 runs to Songgwang Temple every 30 minutes from Suncheon Station.

Once frequented only by herb gatherers, slash-and-burn farmers, or residents of local villages in a hurry, the mountain path became a popular one-day trek when Mt. Jogye was named a provincial park in the 1980s. Some 400,000 visitors now enjoy the tree-canopied path annually. Seonam and Songgwang temples at either end are no ordinary mountain temples. Not only are they ancient places more than one thousand years old, they are among the few renowned chongnim (literally “dense forest”), referring to a temple complete with training centers and monastery housing many monks.

Songgwang Temple is one of the Three Jewel Temples of Korea, which represent the three pillars of Buddhism: the Buddha, the dharma and the sangha, the community of monks and nuns. It is home to the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, thus the name of the mountain, which traces back to the early Zen patriarchs of Mt. Caoxi in China. It has produced more of the nation’s most eminent monks than any other temple, and is a sought-after destination for overseas monks and students of Korean Buddhism.

Seonam Temple belongs to the Taego Order, a splinter group from the Jogye Order. The temple was recognized for its value in preserving and transmitting the Buddhist culture of Korea with its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2018. Within it are many s designated Korea’s “National Treasures.”

The stature and history of these temples obviously give the hike on the mountain path a celebrated quality. Though they may not be old and virtuous monks, hikers are moved by the thought of following in the footsteps of ascetics who shed the bonds and anxieties of the mundane world and traversed this path in search of enlightenment. Among them are frail travelers breathing heavily while wishing they could unload even their shadows before another uphill stretch. There are also members of hiking clubs striding effortlessly and sounding like guides when asked for directions. They all can set aside their worries for a while and share in the give and take of consolation and healing that the path offers. Every small stone, every nameless wildflower becomes precious during the interlude, even if consolation is always fleeting.

Seungseon Bridge leads into the compound of Seonam Temple, one of the seven Korean mountain monasteries inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. An eye-catching dragon head is carved in relief in the middle of the underside of the arch.

Samcheong Bridge at Songgwang Temple is smaller than its counterpart at Seonam Temple but has its own beautiful aura. Past Uhwagak, a pavilion built on top of the bridge, is the front courtyard of the temple.

Seonam and Songgwang temples are no ordinary mountain temples. Not only are they ancient places more than one thousand years old, they are among the few renowned chongnim (literally “dense forest”), referring to a temple complete with training centers and monastery housing many monks.

Two stone pagodas from the Unified Silla period (676-935) occupy the yard in front of the main hall, Daeungjeon, of Seonam Temple. The three-story pagodas standing on a two-tiered base are designated National Treasure No. 395.

Songgwang Temple is one of the Three Jewel Temples of Korea, along with Haein and Tongdo temples. It produced 16 eminent monks who became national preceptors, hence is known as the “Temple of the Sangha Jewel.”

Imgyeongdang, on the left of Uhwagak, is one of the most beautiful sights of Songgwang Temple. The building has large windows that enhance the view.

Consolation

If Suncheon Station is your starting point, the big question is which temple to go to first. If you begin with Seonam Temple, you will be inspired by the presence of a robust stream under your feet and the vibrancy of towering hinoki cypress trees that flank the valley. By the time you catch sight of Seungseon Bridge (Bridge of Ascending Immortals), arched like a rainbow over the water, you will already have entered the Pure Land. In early spring, you can also see elegant plum blossoms of varied hues along the stone wall behind the temple’s main hall, Daeungjeon (Hall of the Great Hero). These flowers, growing on native plum trees over 400 years old, are renowned. If the season is further along, you will be greeted by lovely cherry blossoms instead.

At the front gate of the temple, Iljumun (One Pillar Gate), the subtle scent of a sweet osmanthus tree greets visitors. According to folklore, the scent travels a thousand miles and the tree also stands on the moon. In autumn, its small, white petals cover the courtyard in greeting. At this temple, the tall gate, pond and modest buildings are exquisitely arranged around flowering trees to suggest a village.

On a par with Seonam Temple’s Bridge of Ascending Immortals is Songgwang Temple’s Bridge of Three Pristine Deities (Samcheong Bridge). As if the bridge alone left something wanting, a pavilion was placed over it. Its name is Uhwagak, a pavilion where one becomes as light as a feather and rises to heaven as an immortal. This is a special site and place of rest that can only be found at Songgwang Temple. Varicolored leaves, lonely without visitors to watch them as they grow deep in the mountains, are scattered and carried by the stream to finally gather under the pavilion. The water looks cold.

If you visit Seonam Temple in the morning and reach Songgwang Temple as the sun is setting, try to find the highest possible vantage point. When the faraway afterglow seen between the hills shines down on the dark temple halls, the serenity of the sight will stay with you for a long time. The wide courtyard in front of the main hall is the center of the temple. The restrained ground plan is the result of restoration after the original buildings were reduced to ashes in the Korean War. Whichever temple you take for your starting point, try to stay as long as possible. Peace, too, is always fleeting.

Past the top of Gulmokjae, a 40-year-old barley rice restaurant is a welcome sight on the downhill stretch. A dish of barley rice mixed with assorted seasoned greens and red pepper paste is one of the pleasures of the trail.

Buril Hermitage on the hill behind Songgwang Temple is where the Venerable Beopjeong (1932-2010), revered for his upright character and self-discipline, resided from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s. Here, he wrote “Non-possession” (Musoyu), his famous book of essays.

Peace

Starting from Seonam Temple, the first hill you will come to is Gulmokjae. It lies beyond a hinoki forest and a rock where a tiger supposedly sat with his chin propped on his paw, looking into the hearts and minds of passers-by. This section of the path, with the summit of Mt. Jogye to the north, is quite steep but the trek grows less taxing after the hill. Coming from the opposite direction from Songgwang Temple, you will walk along the valley for most of the way, crossing a sturdy wooden bridge and passing a rock that supposedly rolled down the mountain and threatened to block the path before being stopped by a monk exercising his spiritual powers. The name “Gulmokjae” is inscribed on a nearby stone marker. When climbed from the Seonam Temple side, the hill is called “Big Gulmokjae.” Coming from the Songgwang Temple side, it is named “Little Gulmokjae.” This is the watershed of Mt. Jogye, which lies in the Honam [Jeolla] artery of mountains. Water flowing down the eastern slope heads for Suncheon Bay, while water flowing down the western slope runs to the sea off Beolgyo.

Past this hill and along a downhill road, a barley rice restaurant unexpectedly appears. Black rye bread in Europe and coarse barley rice in Korea shared the same social plateau. While the well-off minority ate white bread made from wheat and pure white rice, rye bread and barley rice sustained the poor. Of course, barley is marketed these days as a health food evoking nostalgic memories.

Once a sort of shelter d from the restored settlement site of slash-and-burn farmers, this restaurant is now seen almost as part of a package tour for hikers to Mt. Jogye; no one passes by without going in. The menu is simple: barley steamed with rice in a big iron cauldron, side dishes made from wild mountain greens gathered nearby and vegetables grown in the kitchen garden, all served up with bean paste soup cooked with dried radish tops. For anyone who has walked an hour or two up to this spot 600 meters above sea level, this is a feast beyond compare. Sometimes, groups will make the 20-minute ascent from Jangan Village solely to have the meal. Indeed, the fastest way to reach this renowned restaurant is to drive along the alleyway winding up to the top of village, park there and then do the short hike.

The taste is not easily described but everyone quickly empties their bowl. Hence, the place could be called the “tastiest barley restaurant.” However, whether in the past or present, the sense of fullness barley gives has never been quite comfortable. This isn’t because one tends to eat more than usual or soon feels hungry again. Rather, the fullness makes you wonder whether you’re simply becoming accustomed to somehow fending off the natural feeling of hunger.

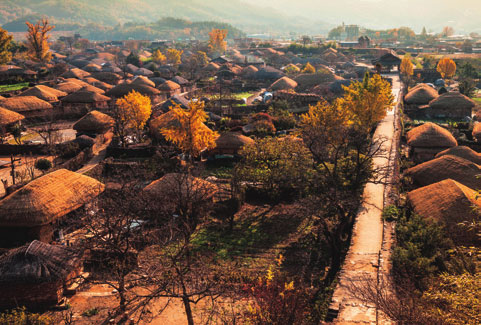

Nagan Town Fortress and Village

Suncheon Open Filming Set

Suncheon Bay National Park

Suncheon Bay Nature Reserve

History

All paths are fleeting. The same could be said of consolation, peace and that feeling of fullness. The rock where the tiger is said to have sat and observed the hearts and minds of people passing by and the legend of the monk who managed to stop a large rock from rolling down and blocking the path with his mysterious power are more than just fanciful tales. Condensed within them is the history of the road over Gulmokjae, cut off and reconnected countless times over more than one thousand years.

In modern Korean history, the term “ppalchisan” refers to an armed band of partisans that formed during the Korean War. Mt. Jogye was an important base for their activities and a connection to their stronghold at Mt. Jiri. The valley of Honggol, not far from Songgwang Temple, was a hideout for the partisans and the site of a pitch battle that would have cost all their lives had they not repelled the attack. Many elderly people staying at the temple were killed. The same road on which people in those days fiercely hunted down their enemy and were hunted in turn is the very road that is introduced here.

Later came an incident that would lead to much more fundamental and lasting conflict. In 1954, shortly after the Korean War ended, then President Syngman Rhee insisted that married monks were a remnant of Japanese colonial rule and therefore should be driven out. Korea had no tradition of allowing Buddhist monks to marry and during the latter part of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), when the monarchy suppressed Buddhism, it became customary to treat laymen who looked after the temple housekeeping as monks. During Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945), Korean monks were influenced by Japanese Buddhism, which began to allow monks to marry by law during the Meiji period. By 1945, Korea had more married monks than celibate monks.

Han Yong-un (1879-1944), poet and monk, wrote in his 1913 book “Restoration of Korean Buddhism” (Joseon bulgyo yusinnon), “It is nonsense to say that anyone born with a physical body has no desire for food or sex.” He urged monks to choose freely for themselves.

Interference by the state in a matter that should have been solved within the Buddhist community was more disruptive to temples than damage from the war. The Supreme Court ruled in 1969 that all religious authority lay with ordained, celibate monks. Those who protested this decision formed the Taego Order of Korean Buddhism, with Seonam Temple as its headquarters. Before, monks of the two temples would come and go in search of masters and companions to learn from and share with. No longer. Conflict regarding property rights to the temple is ongoing.

Nidanas

The dawn service at Songgwang Temple is a pious occasion. Traditional musician Kim Yeong-dong has taken the grandeur and musicality of the Buddhist service and developed it into music for meditation. On top of the sound of the temple’s four instruments (dharma drum, wooden fish, cloud-shaped gong and temple bell) as well as the words of the service, prayers and the Heart Sutra, he overlaid a mix of synthesizer music and the sound of the daegeum and sogeum (traditional bamboo flutes). The result is a 1988 LP album titled “The Buddhist Meditation Music of Korea.” Anyone who enjoys Gregorian chants should listen to the last track on this album, “Banya Simgyeong,” the Korean name for the Heart Sutra. It is moving in a different way than New Age meditation music. There is also a CD album recorded in 2010 by professional sound engineer Hwang Byeong-jun.

Natural sounds, such as wind, have been removed to help listeners focus on the sounds and reverberations of the old timber building. If the charm of Kim’s music is finding the hidden sounds in nature and being whisked away to a new space, Hwang’s music leads us into time that disappears without a trace.

Kim says he was inspired to make the album when he visited the Venerable Beopjeong (1932-2010) at Buril Hermitage of Songgwang Temple. For living up to his creed of “non-possession,” the monk was widely respected not just within the Buddhist community but far beyond. The Sino-Korean term for non-possession is musoyu. The smallest unit of meaning, the seme, is represented by the character yu (有), meaning “to have,” which evolved from a character in the ancient Chinese oracle bone script depicting a hand grasping a fish. A chair made by Beopjeong from oak kindling still sits in front of the hermitage; on it rests the leaf of a magnolia tree. Had the old monk seen it, he may have responded, “Dear leaf, take a rest. You’ve worked so hard, hanging on that tree.”