Located in the center of the Korean peninsula, Yeoju is a river city long appreciated as a hub of both shipping and the ceramic industry. Rice from this region is also highly regarded for its quality. But opinion is divided on the strengths of Yeoju’s storied ancient temples and surrounding environs as a must-see tourist destination.

The Pasa Fortress in Yeoju, Gyeonggi Province, provides a clear view of the Namhan River and surrounding mountains.

Built by Silla in the mid-sixth century during the Three Kingdoms period, the fortress walls are some 950 meters in

circumference and up to 6.5 meters high. Any hostile forces approaching on the river were easily detected.

“My Exploration of Korean Cultural Heritage” was something of a sensation when the inaugural book in the series appeared in the early 1990s. It became the first Korean humanities book to sell over a million copies and sparked a nationwide craze for exploration. In an eloquent, approachable style, art historian Yu Hong-june introduced a new way for Koreans to appreciate their cultural heritage while simultaneously enlightening international visitors.

In the eighth volume of his series, Yu suggests two courses for visitors who have only one day to explore the country’s culture and natural environment. One of these is a tour of Yeoju, an hour’s drive from Seoul.

The author’s reasons include Yeoju’s treasures: Silleuk Temple, which has “the warm, comfortable atmosphere of a Korean Buddhist temple”; the site of Godal Temple, where the “ambience of the ruins of an ancient temple” can be felt; and the tombs of King Sejong and King Hyojong with their “dignity and solemnity.” Yeoju, he also points out, offers wonderful views of the Namhan (or South Han) River. In 2012, CNN GO picked Silleuk Temple as one of the 50 most beautiful places to visit in Korea.

While these attractions may entice international tourists, they are simply pedestrian to many Koreans: ordinary and familiar. Domestic readers are hardly persuaded by Yu’s explanations of the temples’

aesthetic values. Why does he bypass other historical sites with more obvious splendor and scenic spots whose beauty has been rhapsodized? Why does he recommend plain old Yeoju?

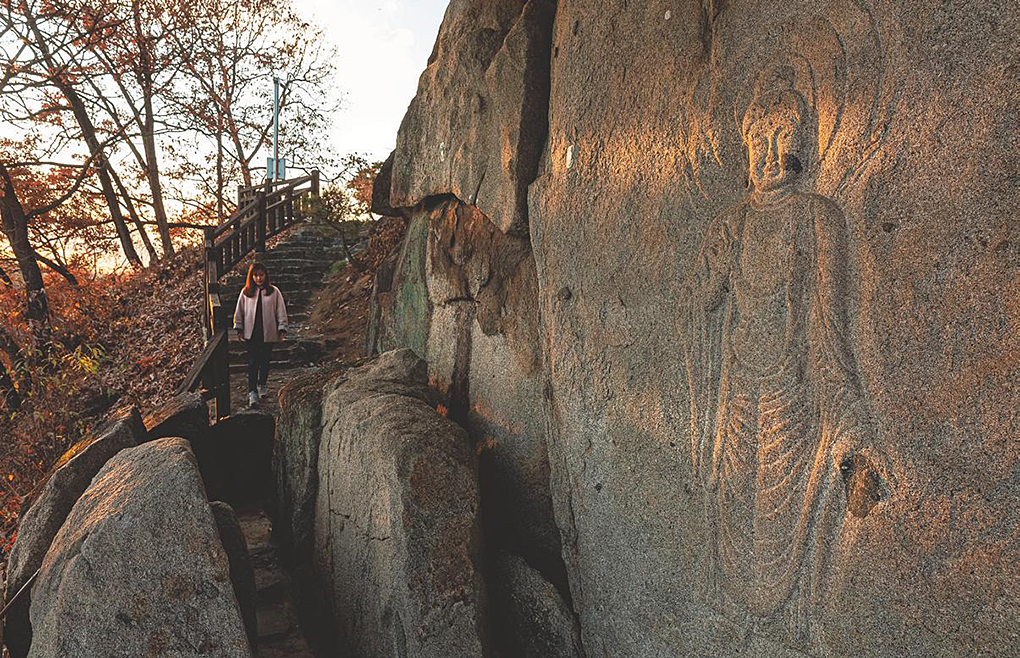

The standing Buddha image, 223cm

high and 46cm wide, carved into the

cliffside along the Namhan River, is an

early Goryeo (935-1392) work that

continues the style of the Unified

Silla (676-935), as evidenced by the

detailed drapery and the refined

lotus pedestal and halo.

The brick pagoda at Silleuk

Temple stands on the rocky edge of

the temple grounds, overlooking

the Namhan River. The 9.4-metertall pagoda, designated Treasure

No. 226, was likely influenced by

brick construction introduced to

Korea from China around the

10th century.

The Invisible Land

When Western doctors first encounter Asian medicine, they are often surprised to see that its diagrams of human anatomy scarcely show any muscles. Instead, they focus on acupuncture points and the flow of gi (qi in Chinese), or vital energy, in the human body.

Francisco Gonzalez-Crussi, a Mexican doctor and writer, attempted to explain these two different views of the human body and the world. Essentially, he summarized that while Westerners tried to reveal the complex system of the human body through the muscles, a voluntary tool expressing will, Asians sought to understand the non-voluntary and invisible pulse of the blood vessels and the heart as the source of the body’s movement.

In this sense, perhaps Yu wanted to show the “invisible energy” of Korea’s natural environment and cultural heritage rather than their “muscles.”

Koreans interpret land in terms of pungsu jiri (geomancy, or the Korean equivalent of feng shui). These words translate literally to “wind and water” and “understanding the land,” respectively. To understand pungsu, one needs to understand gi. Its common translation of “vital energy” has no real equivalent in Western culture. Gi is defined as the source or basis of all matter that has shape or form. A time-honored idea in Asian philosophy is that gi inside the land breathes life into all things. The study of this invisible energy of the land is pungsu.

Yeoju is like Seoul in many ways. Running through both cities, surrounded by lovely stretches of mountains, is the Han River, which divides the central part of the Korean peninsula as it flows east to west. A Yeoju-to-Seoul boat ride on the Han is a day’s journey. Thus, in the past, Yeoju’s famous rice, as well as salt, salt-fermented fish (jeotgal) and fresh seafood from the west coast could reach the capital the day they were shipped.

Vibrant River Town

During the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), grain was used to pay taxes and shipped on the Han River. Yeoju served as a sort of midway point for merchant ships and boats carrying tributary goods, and intellectuals and government officials with a discerning eye for places to live began to converge here.

When the capital was moved to Hanyang (today’s Seoul) at the start of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), Yeoju became home to those in positions of power and influence. This significantly enhanced the town’s political and cultural stature. Consequently, more than one fifth of all Joseon Dynasty queens hailed from Yeoju and the region is home to more pagodas and other historical structures of National Treasure or Treasure level than any other part of the country.

Despite its speed and convenience, transporting cargo by water was risky. An accident often resulted in loss of both property and lives, and it was a common custom among the boatmen to pray to the Buddha for their safety. Among Korea’s ancient rock-carved Buddhas, only two are situated along a river. Both overlook the Han. One is located beside the old Geumcheon river port in Changdong-ri, Chungju. The other is at Bucheoul (literally “Buddha Rapids”) in Gyesin-ri, just above the old Ipo river port in Yeoju.

The rocks on which the two Buddhas were carved differ in scale, form and material composition. But both were made during the Goryeo Dynasty, carrying on the style of the Unified Silla (676-935). River passengers and crews would look up at the Buddhas and pray for a safe journey.

Presumably founded during

the reign of King Jinpyeong

(r. 579-632) of Silla, Silleuk

Temple is prized for its cozy,

warm atmosphere. Found

within its grounds are statedesignated treasures,

including a stone lantern,

a brick pagoda and the

Treasure Hall of Paradise.

Brick Pagodas and Jade-Green Celadon

Unlike most Korean Buddhist temples, which are nestled in the mountains, Silleuk Temple faces the river flowing alongside its grounds. The temple’s oldest remaining architectural structure is a brick pagoda that sits on a rock overlooking the Han. Though the layout of Buddhist temples is now based on the main hall as the center, there was a time when the pagoda was the central point around which all the buildings were arranged.

The Han River has the largest water volume of any river in the southern half of the Korean peninsula. Its narrow width combined with heavy rainfall led to frequent summer flooding in the past.

The brick pagoda of Silleuk Temple stands on a high cliff at a particularly rough section of the river that has capsized many vessels. Placing the pagoda on the cliff was a way to alert passing boats of impending danger. This is an example of bibo, the geomantic principle of offsetting the deficiencies of a site. If the rocks and mountains are the muscles of the land, the rivers are its blood vessels. Placing the pagoda on the cliff was meant to suppress the negative energy of the terrain and purify its “blood” by making it clean and gentle. These days, the purpose of the pagoda is overlooked. It is even hidden from view by Gangwolheon, or the Pavilion of River and Moon.

Brick pagodas were a rarity in Korea, which lacked a brick-making tradition. That changed when Silla sent Buddhist monks to China to learn the latest trends in Buddhism. Their sojourns led to the adoption in Korea of many systems and cultural aspects of China’s Tang Dynasty, including brick pagodas.

Not far from Silleuk Temple is the site of a Chinese-style brick kiln. It dates back to the latter half of the 10th century, during the Goryeo Dynasty, around the same time the brick pagoda at Silleuk Temple was constructed. One can imagine Chinese potters coming to Korea, crossing the West Sea and supervising the construction of the pagoda, a project which Goryeo potters helped to complete. The evidence of this is found in the floral scroll design called dangcho – literally “Tang grass” – that adorns the bricks.

The introduction of the brick kiln also led to the birth of the Goryeo jade-green celadon so highly praised by Xu Jing, a Song Dynasty envoy, in his 1123 book “Illustrated Account of Goryeo” (K. Goryeo dogyeong, Ch. Gaoli tujing). Chinese-style brick kilns were primarily operated in Gyeonggi Province, adjacent to the capital. Gradually, Goryeo potters changed these brick kilns to Korean-style earthen kilns and departed from the Chinese method of firing once at a very high temperature. The technique of two-step firing – bisque firing followed by glaze firing – spread throughout Korea. It enabled the production of ceramics in any place where clay could be easily obtained and, in turn, stimulated the development of high-quality Goryeo celadon wares. This tradition of pottery making has continued over the centuries. Today, some 400 pottery workshops operate in the Yeoju area.

The site of Godal Temple, some 60,000 square meters in total area, indicates

the size and scope of the vanished temple. Built in the latter half of the eighth

century, the temple flourished for several hundred years. Two exquisite stupas

and other cultural treasures made of stone remain on the grounds.

This stone stupa, designated National Treasure No. 4, stands 4.3 meters

high on a low hill at the back of the Godal Temple site. Dating to the Goryeo

period, the stupa is recognized for its refined form and sculptural technique

displayed in the dragon and tortoise carvings on the shaft.

Land that Lives and Breathes

There were two main overland routes from Seoul to Yeoju: one went to the north of the Han River, the other to the south. On foot, either of these journeys took two days.

The northern route evolved during the Three Kingdoms period (57 B.C.-A.D. 668). It linked the Namhan River with villages and temples and connected them to water transportation. From Pasa Fortress in Yeoju, the view over the river is spectacular. The wide open vista to the south shows Ipo Bridge slung over the long watercourse flowing to the west. To the north, the peaks of the Taebaek Mountain Range can be seen in the distance. If you stand there, questions as to why the fortress was built on this spot and why the Three Kingdoms – Goguryeo,

Baekje and Silla – fought so long and hard over this land naturally disappear. This is also the bitter road traveled by two Goryeo kings: King Mokjong (r. 997-1009) when he was overthrown and exiled to Chungju, and King Gongmin (r. 1351-1374) when he took refuge in Andong upon the invasion of the Red Turbans.

The route also reveals the vast, empty site where Godal Temple once stood. Nestled against Mt. Hyemok, an aura of history still shrouds the vacant expanse. During the Goryeo period, the temple grounds stretched over 30 li (approx. 12km) in all four directions and were home to hundreds of monks, an indication of how the Goryeo royal court showered the temple with privileges and financial support. When Goryeo gave way to the Confucian state of Joseon, the favors and support of the state ended and Buddhism was unable to survive on its own.

Remaining on the site are some excellent works of Buddhist art, including stone stupas and pagodas such as the Stupa of Godal Temple (National Treasure No. 4), which features intricate carvings. Though worth seeing for their sculptural beauty alone, the pagodas are also fascinating as examples of symbolic temple structures erected to protect and proclaim the authority of the throne by borrowing from the energy of the land.

Standing on the temple site today, no matter how much you look around, mountain scenery unfolding to your left and right, it is hard to detect traces of the grandeur of the temple that once stood there. But when strolling along the hills behind the ruins, listening to the sound of the wind blowing cold, somehow you feel warm and comfortable, your mind neither empty nor scattered. It is probably a feeling that comes from a land that is alive and breathing.

The tomb of Queen Inseon, located just below the tomb of King

Hyojong (r. 1649-1659) of Joseon, is surrounded by stone figures.

The Yeongnyeong Royal Tombs include the joint tomb of

King Sejong (r. 1418-1450) and Queen Sohyeon in the western

compound, and the double tombs of King Hyojong and Queen

Inseon in the eastern compound. These tombs exude the dignity

and solemnity that marks the royal tombs of the Joseon Dynasty.

Eyes of Wisdom

The southern route to Yeoju from Seoul forms part of the road network that led from the capital to Dongnae in Busan during the Joseon period. It was the road traveled by King Sejong (r. 1418-1450) when he visited Yeoju, home of his maternal relatives, during his hunting trips, and by the kings who came after him when they traveled to Yeoju to pay respects at his tomb or, in much later years, the tomb of King Hyojong (r. 1649-1659). The tomb of King Sejong, originally located in Gwangju, was moved to Yeoju in the belief that its present site was the most auspicious land in the country.

A little to the southeast of King Sejong’s tomb is Yeongwollu, or the Pavilion of Welcoming the Moon, which is known to offer the finest elevated view of the Han River. From here you can see the whole downtown area of Yeoju to the west, and if you lift your head to the north you will see, across the river, the mountains spread out like a landscape painting, some close by and others in the distance. Among them is Mt. Hyemok, towering over the site of Godal Temple. Hyemok is a Buddhist term for the “wisdom eye.” The “Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment” speaks of sentient beings who “have clarified their optical illusions and purified their wisdom eye.” No matter how high I rise, my mind and body are unaware of it. Does this mean that for me, the purified wisdom eye is still far off?

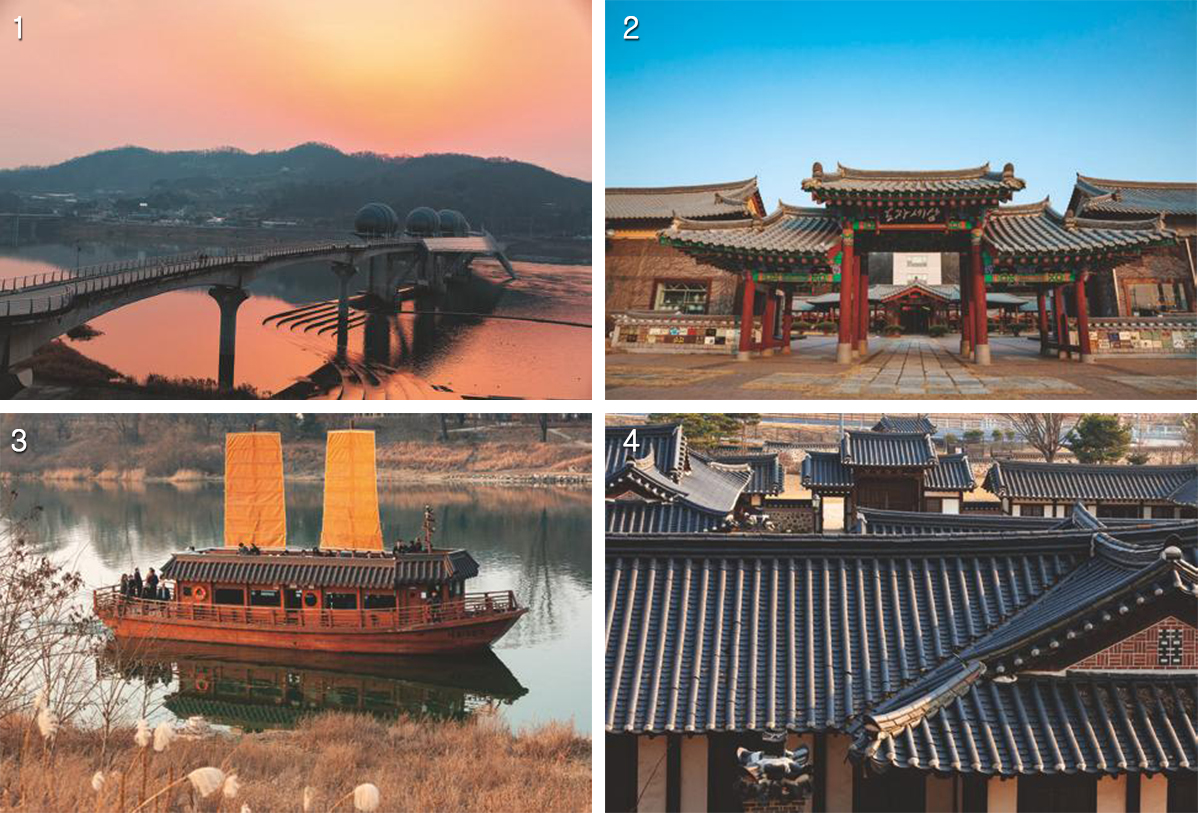

1. Ipo Bridge 2. Yeoju Ceramic World 3. Old Ferry Crossing 4. Birthplace of Empress Myeongseong