Dictionaries mirror cultural and social changes through the words they list and their definitions. “Dictionaries of Korea, A New Perspective,” a special exhibition at the National Hangeul Museum, provided a unique opportunity to look back on the modern era.

“Dictionaries of Korea, A New Perspective” was a special exhibition held at the National Hangeul Museum from September 20, 2018 to March 3, 2019. A visitor examines the dictionaries and the changes in sociocultural trends reflected in them.

In 2010, Oxford University Press announced that it would no longer print its “Oxford English Dictionary” (OED), the most authoritative dictionary of the English language. Faced with a huge decline in annual sales of its print dictionaries, the company said its third edition of OED would only be available online.

The first part of the OED’s first edition appeared in 1884 and its first complete edition was released in 1928. The latest edition contains 10 Korean words, including taekwondo, kimchi, makkoli (unrefined rice wine, also spelled makgeolli) and ondol (floor heating system), as well as chaebol (large family-owned business conglomerate, also spelled jaebeol) and won, the Korean monetary unit.

Korea bid farewell to print dictionaries four years earlier. On Hangeul Day, October 9, in 2006, the National Institute of Korean Language said the revised edition of the “Standard Korean Language Dictionary” would be restricted to online viewing. Since then, the institute has beefed up the services of its online dictionary, introducing “Urimalsaem,” literally “spring of our language,” an open interactive dictionary that accepts new words and definitions from users.

The transition from print to online has paralleled technological advances. The omnipresence of computers and smartphones means their owners are literally walking around with small dictionaries. The internet has made finding a definition or word in digital and online dictionaries simple and easy. Gone are the days of riffling through the pages of a paper dictionary looking for a word. Curiously, however, more than a few people recently queued up simply to look at dictionaries.

The special exhibition, “Dictionaries of Korea, A New Perspective,” began on September 20, 2018, at the National Hangeul Museum, located on the compound of the National Museum of Korea in Yongsan District, central Seoul. Although originally scheduled to close at the end of the year, public reception was so favorable that it persuaded the museum to grant an extension until early March.

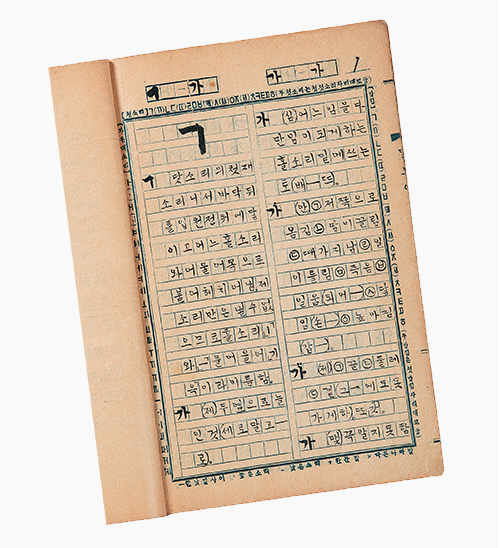

The manuscript of the first Korean dictionary that Ju Si-gyeong (1876-1914) began writing with his students in 1911. Only parts of the original manuscript still exist. © National Hangeul Museum

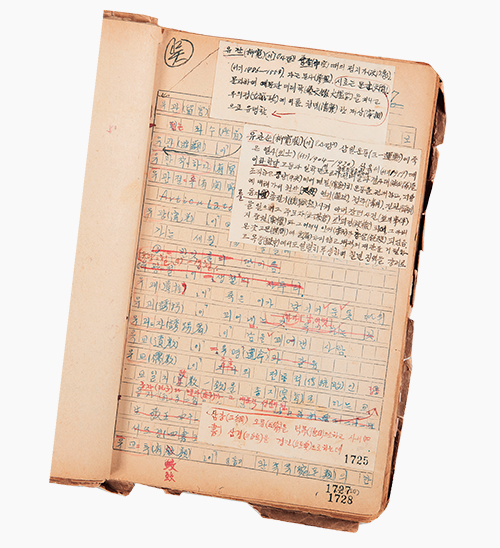

The final draft of the “Dictionary of the Korean Language,” which was compiled over a period of 13 years starting from 1929 by the Korean Language Society, founded in 1921. The manuscript was seized by the Japanese police in 1942 and recovered in a warehouse at Seoul Station in 1945 after the nation’s liberation.© Hangeul Society

Historic Manuscripts

Dictionaries are not only a treasure trove of words. They also provide insights into the evolution of nations and societies. Pause and reflect on the etymology of words and you realize that dictionaries provide more than just definitions. They also track social, cultural and historical developments. In this respect, the exhibition offered the delightful experience of being transported 100 years into the past to explore how dictionaries have changed with the times.

King Sejong (r. 1418-1450), the fourth monarch of the Joseon Dynasty, d Hangeul in 1443 and promulgated it three years later, but the Korean alphabet was not officially recognized until 1894 under the royal edict of the Joseon government. Thereafter, the compilation of Korean language dictionaries became undertakings of national significance in a dark, turbulent period of the nation’s modern history. No doubt the upheaval slowed the projects considerably.

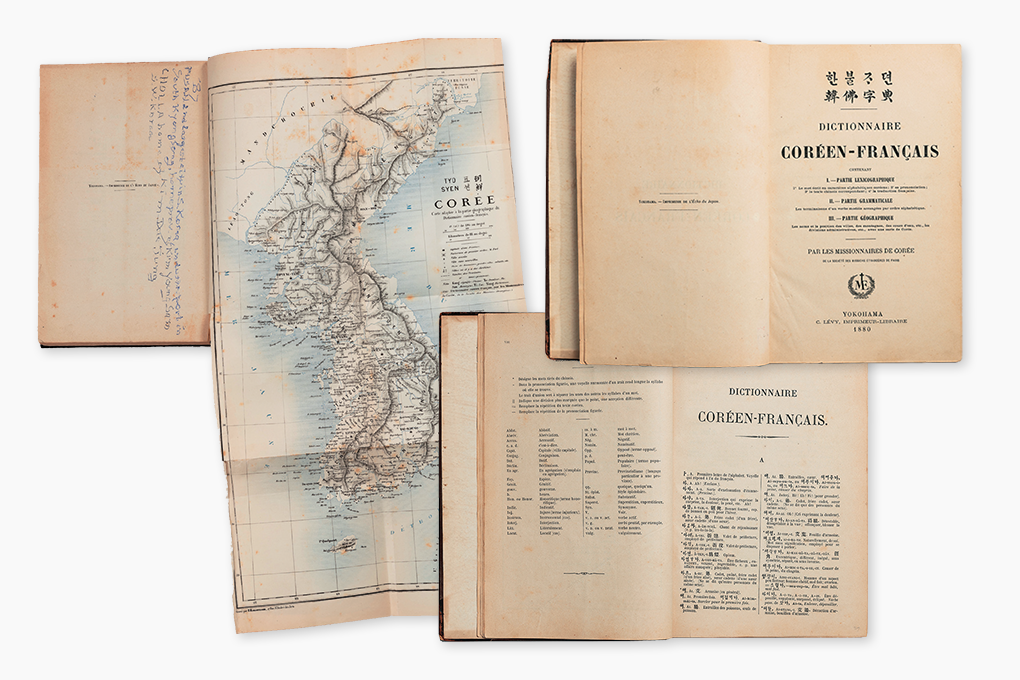

The first Korean language dictionary written by a Korean did not appear until the 1930s. But far earlier than that, foreign Christian missionaries produced bilingual Korean dictionaries - the first being “Dictionnaire Coréen-Français,” published in 1880. A Korean-English dictionary followed in 1890 and an English-Korean dictionary the next year.

The handwritten draft of “Dictionnaire Coréen-Français,” dated 1878, was among the highlights of the exhibition. Held by the Research Foundation for Korean Church History, the draft manuscript was shown to the general public for the first time alongside its print version. Bishop Félix-Clair Ridel (1830-1884) from La Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris (Paris Foreign Missions Society) published the dictionary in Yokohama, Japan, in 1880. It is of immense historical value because it is not only the first Korean-French dictionary but the first-ever Korean bilingual dictionary in a modern sense.

Photograph of members of the Hangeul Society taken on October 9, 1957, commemorating the publication of the “Dictionary of the Korean Language.” The compilation of the dictionary that began in 1929 had to be discontinued due to the imprisonment of the society’s lexicographers, and was completed after the nation's liberation from Japanese rule. © Hangeul Society

Also displayed to the public for the first time were unfinished dictionaries written by independence activists during the closing years of the Joseon Dynasty, when foreign powers were encroaching on Korean territory.

Among these dictionaries was one that shed light on a lesser known fact about Syngman Rhee (1875-1965), the first president of the Republic of Korea. In 1903-1904, toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty, while he was jailed on charges of attempting to overthrow the monarchy, Rhee wrote the draft of the “New English-Korean Dictionary.” Unfortunately, the dictionary never reached printing presses. Rhee, an independence activist who advocated republican rule, only completed the words from A to F because he was also devoting his time to writing “The Spirit of Independence.” Today, Rhee’s handwritten draft is owned by the Syngman Rhee Institute at Yonsei University.

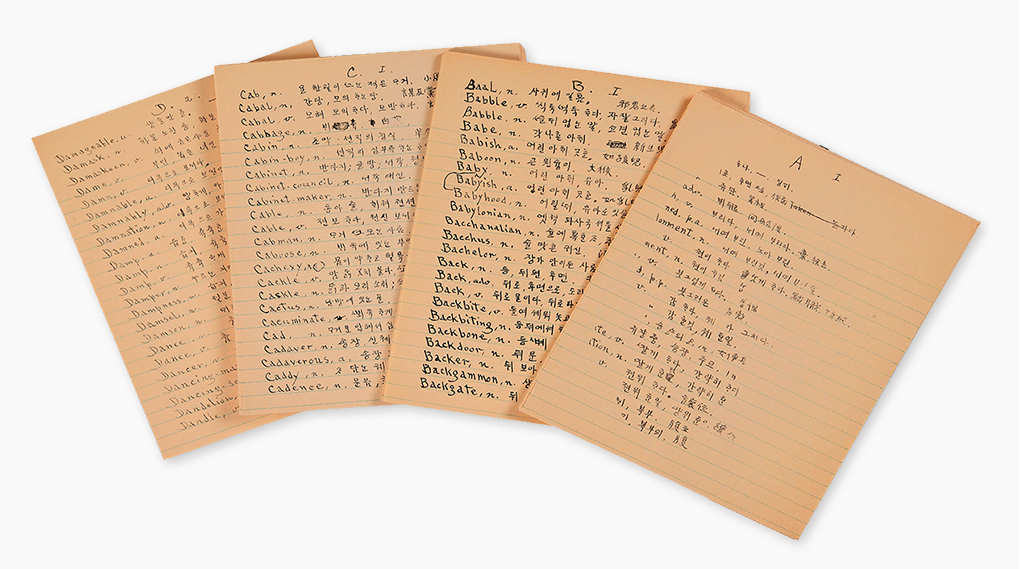

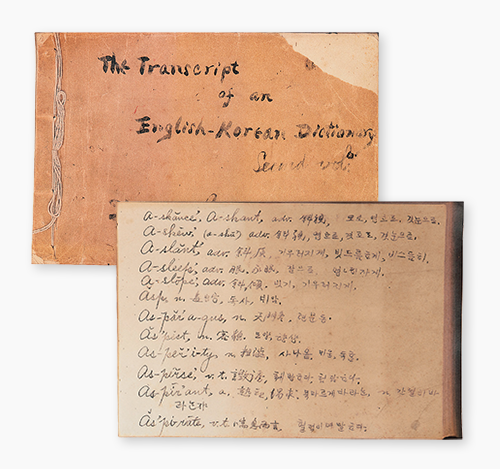

Another unfinished dictionary stemmed from independence activist and journalist Soh Jaipil (a.k.a. Philip Jaisohn; 1864-1951). In 1896, Soh founded The Independent, the first Korean-English bilingual newspaper published in Korea. Around that time, Soh embarked on the first draft of an English-Korean dictionary, but he only managed to complete A to P. His handwritten manuscript, dated 1898, was loaned from the Independence Hall of Korea.

“Dictionnaire Coréen-Français,” published by Bishop Félix-Clair Ridel (1830-1884) from La Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris (Paris Foreign Missions Society) in 1880. The first bilingual Korean dictionary contains some 27,000 Korean entries in alphabetical order.© National Hangeul Museum

Modern Words

The exhibition also provided telltale evidence of the changes in the spelling and meaning of words over time. They reflected Korea’s sociocultural transition since the enlightenment period, as well as how Korean people’s perceptions have evolved.

For example, the 1925 short story “Telephone” (Jeonhwa) by Yeom Sang-seop (1897-1963), an outstanding writer and journalist known for his seminal work, “Tree Frog in the Specimen Room,” depicted how the purchase of the modern invention exposed ostentatious human desires and led to the unwanted consequences of giving up one’s privacy.

The telephone was first introduced to Korea in 1898. At first, it was called deongnyulpung (delufeng), a Chinese transliteration of the pronunciation of the English word telephone. The three Chinese characters consisting the name literally mean “the wind that spreads virtue.” Referring to its purpose, telephone was also called jeoneogi, meaning “a machine that conveys words.”

No proper word for telephone existed in Korean up until the 1920s when it was given the name jeonhwa, comprised of the same Chinese characters as denwa, the Japanese word for telephone, which is still used today. The word was socially recognized and added to the Korean vocabulary in 1938 when it was included in the “Korean Language Dictionary,” a compilation of some 100,000 words, written and published by Korean language scholar Mun Se-yeong (1888-?).

Mun’s dictionary was the first Korean language dictionary to be written by a Korean. It resulted from his strenuous efforts over many years to publish a Korean dictionary as a means of restoring a sense of national pride among Koreans deeply wounded by colonial rule. In spite of their historical significance, the bilingual dictionaries written by foreign missionaries in the late 19th century could not satisfy such an aspiration. Moreover, a Korean language dictionary published by the Japanese Government-General of Korea in 1920 was part of a cultural initiative to tighten its colonial grip.

The exhibition thus brought to light when words like automobile, television or electricity were introduced into Korean society in tandem with modern technological progress, and how neologisms reflective of social trends, such as “modern boy,” “modern girl” and “free woman,” emerged.

The publication of the “Standard Korean Language Dictionary” by the National Institute of Korean Language in 1999 was a significant milestone in the history of Korean lexicography. It resulted from an eight-year government project that cost 12 billion won (approximately US$11 million). The dictionary in three volumes has more than 7,000 pages and contains some 500,000 entries, including the standard Korean as spoken in South Korea, the Korean language spoken in North Korea, regional dialects and archaic words. Over the years, it has been the standard reference work for a number of dictionaries produced by commercial publishers.

In today’s digital age, when information overload augmented by convenience and speed is the norm, it is easy to overlook the role of dictionaries in society.

Independence activist Soh Jaipil’s first draft of an English-Korean dictionary written in 1898. He only managed to complete the letters A to P.© Independence Hall of Korea

Driver of Korea’s IT Prowess

In today’s digital age, when information overload augmented by convenience and speed is the norm, it is easy to overlook the role of dictionaries in society. In that sense, the National Hangeul Museum’s exhibition offered a rare opportunity to reflect on the value of dictionaries that have served as guides to the world as well as nourishment for minds. It also helped recall the nation’s tumultuous modern history and ponder the excellence of Hangeul.

Overcoming many difficulties and stalwart opposition by conservative courtiers, King Sejong d the Korean alphabet for the convenience of the majority of people who had no access to classical Chinese education. The original name of the alphabet, Hunmin Jeongeum (Proper Sounds to Instruct the People), testifies to the sage king’s pragmatism and benevolent desire for universal literacy. The indigenous Korean alphabet has been globally recognized as being one of the most scientific writing systems, which is easy to learn and use. It is also the only writing system in the world that can identify its creator, creation date and purpose. Therefore, “Hunmin Jeongeum Haerye,” the manuscript that contains the proclamation of the new alphabet and explanations and examples of its usage, was included in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 1997.

The annual UNESCO King Sejong Literacy Prize commends institutions and individuals who have fought against illiteracy. The recipients are announced on International Literacy Day, September 8.

A crucial reason for Korea’s rise to a global IT powerhouse boasting coveted internet connection speed and mobile communications is attributed to the simple and scientific structure of the Korean alphabet, which, as Sejong himself wished, “everyone can learn with ease and use with comfort.”

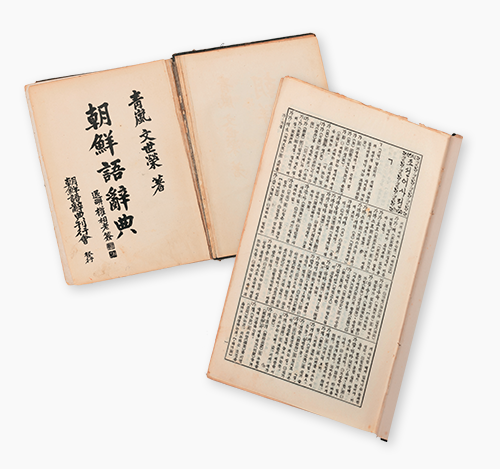

The inside cover and first page of the “Korean Language Dictionary” written and published by Mun Se-yeong in 1938. Containing around 100,000 entries, it was the first Korean dictionary to use the Unified Hangeul Orthography. A revised and enlarged edition was published in 1940 with 10,000 additional entries and amended annotations.

The unfinished draft of the “New English-Korean Dictionary” written by Syngman Rhee, the first president of the Republic of Korea, in 1903-1904, while he was in jail. © Syngman Rhee Institute, Yonsei University

Hong Sung-ho Editor, The Korea Economic Daily