A floor heating system exemplifying the traditional fire-handling skills of Koreans, ondolhas profoundly influenced their lifestyle. Today, the household habits shaped many centuries ago by the unique heating method continue in certain forms. This is why ondol is recognized as a “national intangible cultural property.”

A guest room of the old clan head house of Jang Heung-hyo (1564–1633, pen name Gyeongdang), a Confucian scholar of the mid-Joseon Dynasty, in Andong, North Gyeongsang Province. The floor of an ondol room is usually given a glossy finish with soybean oil after thick hanji (traditional paper) is pasted on clay covering. The furniture is placed farthest from the fire.

The earliest forms of ondol on the Korean peninsula date back to the Neolithic Period. The underfloor heating system encouraged Koreans to sit and lie on the floor. All household activities - eating, reading, interacting and sleeping - were done at floor level, and to accommodate the activities, various short-legged tables emerged.

Fittingly, the starting point of a home ondol was the kitchen. It became an especially meaningful part of Korean homes. Besides providing nourishment and warmth to the family, the kitchen contained an altar to serve the gods overseeing their welfare, as well as a place of purification.

Many middle-aged Koreans share similar experiences tethered to the heated floors: warming up from the winter cold; putting a rice bowl on the warmest spot on the floor; and reserving the hotspot for the oldest family members and guests. These habits are less frequently seen today as modern houses and apartments are furnished with Western-style tables, chairs and beds. But even the modernized versions of the traditional heating system facilitate the floor-level activities of previous generations. The way of living born from ondol remains present throughout the country. That is why it was recognized as a “national intangible cultural property” by the Cultural Heritage Administration in April this year.

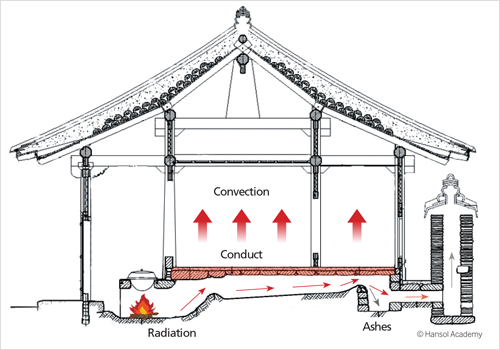

Today, practically every Korean home has a modernized version of ondol, while the traditional heating system is difficult to find. Its main component was the agung-i, a firebox or stove. It was placed beneath floor level, adjoining the kitchen, and functioned more like a furnace to produce radiant heating from a system of flues running under the floor. The complicated structure and function, of course, was quite different from fireplaces.

Agung-i and Fireplace

A fireplace directly heats the room air, a convection heating system. However, the warm air rises and the fire in the fireplace burns oxygen in the room, making the air stuffy. Before the advent of the chimney around the 13th and 14th century in Europe, windows had to be opened to change the air, which wasted the generated heat.

Traditional Chinese houses in most areas lacked any special heating system to handle cold weather. There was hardly any reason to make a fire except for cooking and the houses lacked a chimney. The room where the fire was lit had a high ceiling and a roof consisting of logs about 10 centimeters wide with roof tiles on top of them. Smoke gathered under the high ceiling and disappeared between the roof tiles, along with the warm air. Japanese traditional houses with tatami floor mats also lacked a chimney.

In Korean traditional houses, the kitchen adjoins the main room. Hot air from the kitchen’s agung-i (firebox or stove) flows into the flues under the floor to warm the room.

In the traditional ondol system, the heat from the firebox warms the floor, which, in turn, warms the room air. The radiant heating method has higher thermal efficiency than convection heating produced by a fireplace. Radiant heat easily warms a large space and delivers a relatively even distribution of the room’s temperature. It also does not pick up and circulate dust, as occurs with convection air currents.

Radiant heating can be found elsewhere in the world. Smoke houses in Finland and pechka, the Russian brick stove, are examples. A heating system similar to ondol is the kang, which spread from Hebei Province to the northeastern region of China. The kang is confined to only a part of a room, usually the size of a large bed. Compared to other radiant and convection heating systems, the most conspicuous difference is that the traditional Korean ondol system produced no smoke in the room.

Structure and Principle

In heating a room from the outside, the traditional ondol system is quite unique. Much is required for the system to function properly: the heat has to be collected and sent deep under the floor from the firebox without being lost. At the same time, smoke has to be removed without allowing it to seep up through the floor.

Besides the agung-i, the other primary components of the ondol system are the gorae and the gaejari at the entrance to the chimney. The gorae are underfloor flues that transfer the heat, warming the floor and carrying the smoke to the chimney.

Each flue is about 20 centimeters wide. It usually is built by laying straight lines of bricks on their sides askew toward the chimney. With the brick walls between flues as support fixtures, stone plates some 5 to 8 centimeters thick cover the whole floor and then the stone plates are coated with a solidof mud. These stone plates are called the gudeul. The entry to the flues is beside the firebox so flames extend horizontally when the fuel is lit, and the heat enters the underfloor network of flues with the smoke, which is channeled to the chimney. Although the fire’s passages are well organized, some heat can escape because the firebox is open to the kitchen, which facilitates cooking.

To ensure even heat distribution, proper placement of underfloor flues (gorae) and stone floor plates (gudeul) are of utmost importance. The flues are typically made of bricks stacked in straight lines or in a fan-shaped pattern. The stone plates usually are thicker near the firebox and thinner farther away.

The ondol system is excellent at preserving heat. Once a fire is made in the evening, the room keeps the warmth until the next morning. If the stone floor plates are well laid, only about six logs are needed to keep the warmth for three days. For a meditation room in Chilbul Temple on Mt. Jiri, about half a ton of logs can be burned at once, with the fire keeping the floor and walls of the room warm for up to a hundred days. The room is noted for its “double ondol system” and cross-shaped floor with a raised meditation platform at each corner.

As such, an ondol system can keep heat for a long time, even with only a little fuel, but when a fire goes out and the structure cools, cold air goes through the firebox and the chimney, moistening the flues. If the flues remain moist for a long time, the heat is not easily rekindled, requiring more fuel. To prevent this problem, a crock called gaejari (meaning “dog’s spot”) is positioned near the chimney to catch the moisture collecting inside the flues. The moisture gathered in the crock is evaporated by the heat when the fire enters the flues again. That is why a fire is lit in the morning and evening during the summer rainy season, to dry not only the room but also the humid air under the floor.

Indeed, in the past, a pet dog sometimes went into the pit near the firebox to escape the winter cold. Of course, the dog risked being awakened by the lick of the morning fire. Therefore, anyone who made fire in the morning first checked that the firebox was empty by striking the inside with a stick.

The old home of Sim Ho-taek, a wealthy man who used the pen name Songso, in Cheongsong County, North Gyeongsang Province. Built around 1880, it is a typical house of the noble class of the late Joseon period. Each room connected to the agung-i is heated, but the open, wooden-floored hall is not.

Hot-Water Heating

When a fire is lit in the firebox, the hot air and smoke moves into the underfloor flues. The room is warmed by convection heat through the floor while the smoke disperses through the chimney.

One of the reasons why ondol culture was designated a national intangible cultural asset is that the traditional ondol is fast disappearing. Today, most Korean houses have replaced ondol with a water boiler and pipes laid under the floor to heat the rooms. In a large apartment complex, hundreds or thousands of homes are heated through a centralized hot-water heating system.

Famed American architect Frank Lloyd Wright first used hot water pipes for underfloor heating in the early 20th century. The master of modern architecture encountered the Korean ondol in Tokyo during the winter of 1914.

Baron Okura Kihachiro, a renowned entrepreneur, had commissioned Wright to design the Imperial Hotel. One day, when the architect was shivering from the cold, Okura introduced him to a “Korean room.” It was part of Jaseondang, the former residence of the Korean crown prince, which was moved from Gyeongbok Palace in Seoul.

“We were soon warm and happy again — kneeling there on the floor, an indescribable warmth. No heating was visible nor was it felt directly as such. It was really a matter not of heating at all but an affair of climate.”

Traditional Korean houses are constructed by dovetailing lumber together and therefore are relatively easy to disassemble and rebuild. Wright recalled his experience as follows:

“The climate seemed to have changed. No, it wasn’t the coffee; it was spring. We were soon warm and happy again - kneeling there on the floor, an indescribable warmth. No heating was visible nor was it felt directly as such. It was really a matter not of heating at all but an affair of climate.” (‘Gravity Heat’ from “Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography,” 1943 revised edition)

Wright straightened winding electrical radiators and laid them under the floors of the Imperial Hotel. That was the beginning of hot-water underfloor heating, and Wright applied this system to other buildings thereafter.

A traditional ondol room is also a “healing space.” The smoke-free, radiant heating helps to prevent diseases of the bronchial tubes such as sinus infections and pneumonia. It is also effective in easing neuralgia and arthritic pain. Usually, a cold sufferer can get relief by lying on a warm floor and covering up to induce sweating; nasal congestion is alleviated. The same procedure also helps lower a fever. After an exhausting day, simply sleeping in an ondol room makes one feel light and invigorated the next morning. An ondol room is also quite effective for postnatal care.

Healing Space

These results are explained by the fact that the far-infrared rays radiated from the stones and mud when the room is heated permeate our body and have an effect of therapeutic hyperthermia. Direct heat touching the skin rather than the heat in the air helps blood circulation, and the far-infrared rays increase the body’s level of immunity and help the body recover its self-healing power. This is why scientific experiments and efforts continue to combine these health effects of ondol with modern heating systems.