Korean folk paintings had the roles of shielding against evil spirits and conveying hopes for happiness. An artistic reflection of Koreans’ positivity and resilience, they are now undergoing a modern renaissance.

In the distant past, epidemics were considered to be the work of evil spirits. With that belief, Korean households pasted pictures of Cheoyong, son of the Dragon King, on their front doors to repel the plague god, called yeoksin.

This custom dates back to the Unified Silla period – more specifically to the reign of King Heongang (r. 875-886), when the Korean peninsula enjoyed unprecedented peace and prosperity after Silla unified the Three Kingdoms in the seventh century. Legend has it that King Heongang was in the coastal village of Gaeunpo (present-day Ulsan) when thick clouds and fog suddenly gathered to block his sight. Finding this ominous, the king asked the court astronomer for an explanation. He answered, “It is the work of the Dragon King. You must try to appease him.” So the king promised to build a temple for the Dragon King and immediately the clouds and fog lifted.

In return, the Dragon King sent his son, Cheoyong, to Silla. The king arranged a marriage for Cheoyong and appointed him to a high government position. However, the beauty of Cheoyong’s wife posed a problem. She was so lovely that even the plague god desired her. One bright moonlit night, Cheoyong returned home late and caught his wife in bed with another man. Upon seeing this he lamented, “Two legs are mine, but to whom do the other two belong? The person below is mine, but whose body is taking her? What shall I do?” Then he turned to leave. The plague god was moved by Cheoyong’s magnanimity and promised not to go near any house with his picture on the door.

“Four-panel Folding Screen with Peonies.” 19th-Early 20th century. Ink and color on silk. 272 × 122.5 cm (each panel). National Palace Museum of Korea.Peonies have long been considered a symbol of wealth and honor. A popular motif of art, peonies also adorn furniture and clothing. Folding screens with peonies generally have four, six or eight panels. They decorate homes and are often used at weddings.

Origins and Symbolism

It can be said that the history of Korean folk paintings, called minhwa, goes back to prehistoric rock carvings, but the pictures of Cheoyong are the first known examples to appear in written records. Cheoyong’s way of getting rid of the plague god is also notable. Rather than becoming angry, he sang and danced, thereby moving the plague god and persuading him to flee.

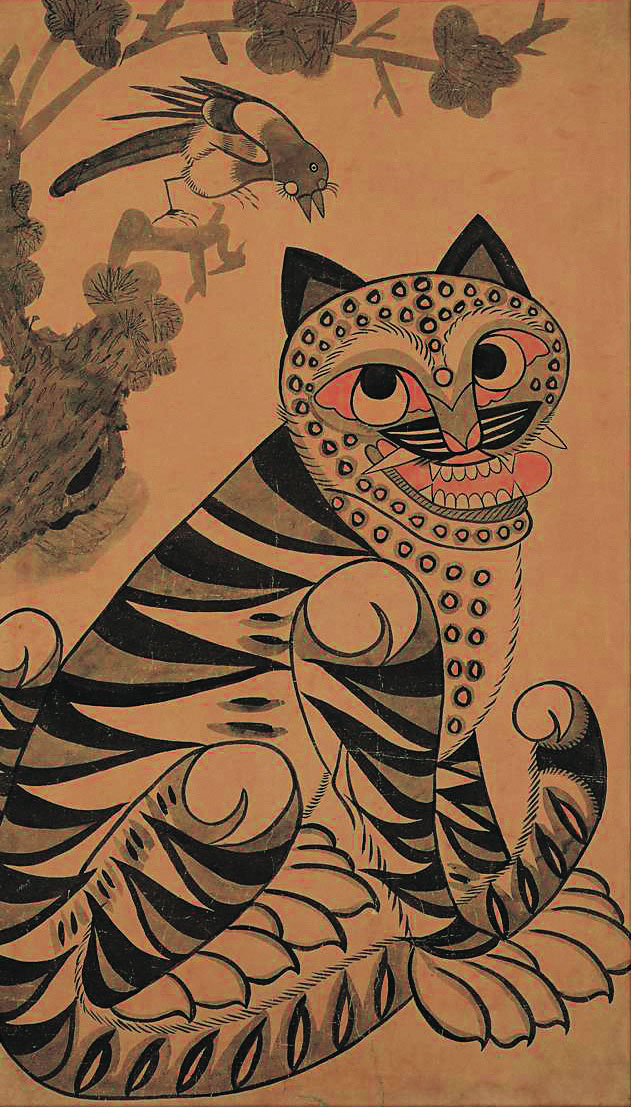

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), pictures of dragons and tigers joined those of Cheoyong at the household gate. On the first day of the Lunar New Year, a picture of a tiger was pasted on one side of the front door and a picture of a dragon on the other. The tiger’s role was to chase away spirits that might try to harm the household; the dragon was believed to attract spirits that could bring blessings. Thus, the two animals were different s of the same purpose: magically engendering peace and happiness in the family.

As commerce developed in the 19th century, the demand for paintings expanded in general throughout Joseon society, leading to a broader range of minhwa motifs and s. Particularly noteworthy was that specific images were used to express wishes for happiness. This led Japanese art historian Fumikazu Kishi, a professor at Doshisha University, to propose that minhwa be called “happiness paintings,” or haengbokhwa.

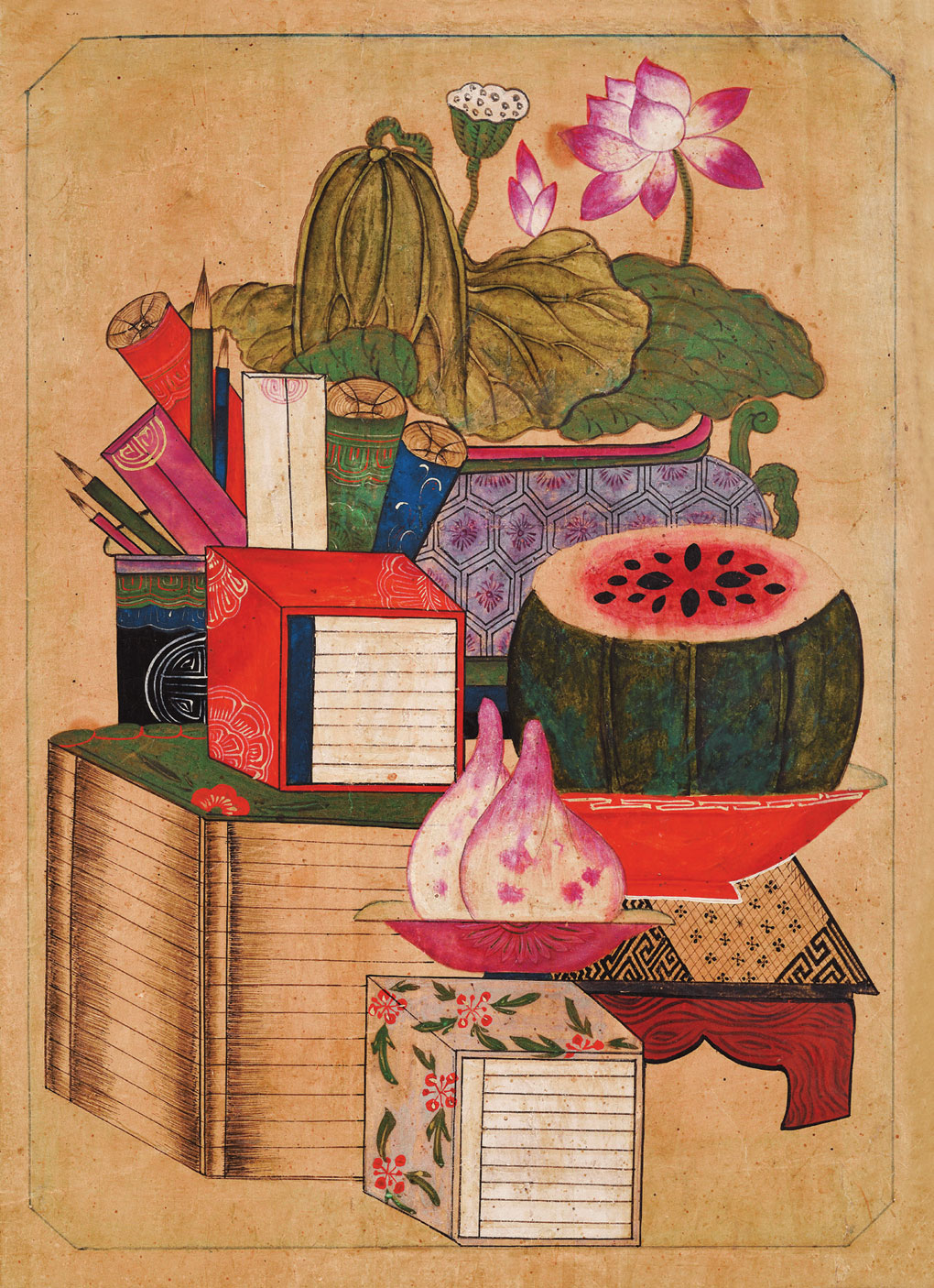

A similar trait also appears in the folk paintings of other Asian nations, including China, Japan and Vietnam. These artworks, which commonly incorporate Chinese characters, embody popular wishes for good fortune, success and longevity. For example, peonies, lotus blossoms, phoenixes and bats symbolize happiness; watermelons, pomegranates, grapes and lotus seeds represent many sons; cockscomb flowers, peacock tails, books and carp reflect aspirations for success; and bamboo, cranes, the sun and moon, tortoises, deer and the mushroom of immortality represent a long life. This common feature of East Asian folk paintings distinguishes them from Western paintings, where not only happiness but love, terror and fear of death are also depicted.

The peony as a symbol of wealth and nobility originates from the poem “On the Love of the Lotus” by Zhou Dunyi, a prominent Neo-Confucian thinker of the Song Dynasty. In this Chinese poem the peony is described as “the nobility of great wealth,” the chrysanthemum as the “recluse of the flowers” and the lotus as the “gentleman of the flowers.” However, in Joseon, such symbolism was unacceptable. Confucius, whom Joseon literati revered, had said, “With coarse rice to eat, with water to drink, and my bended arm for a pillow; I have still joy in the midst of these things. Riches and honors acquired by unrighteousness are to me as a floating cloud.” Therefore, Joseon scholars considered it shameful to discuss worldly possessions and status.

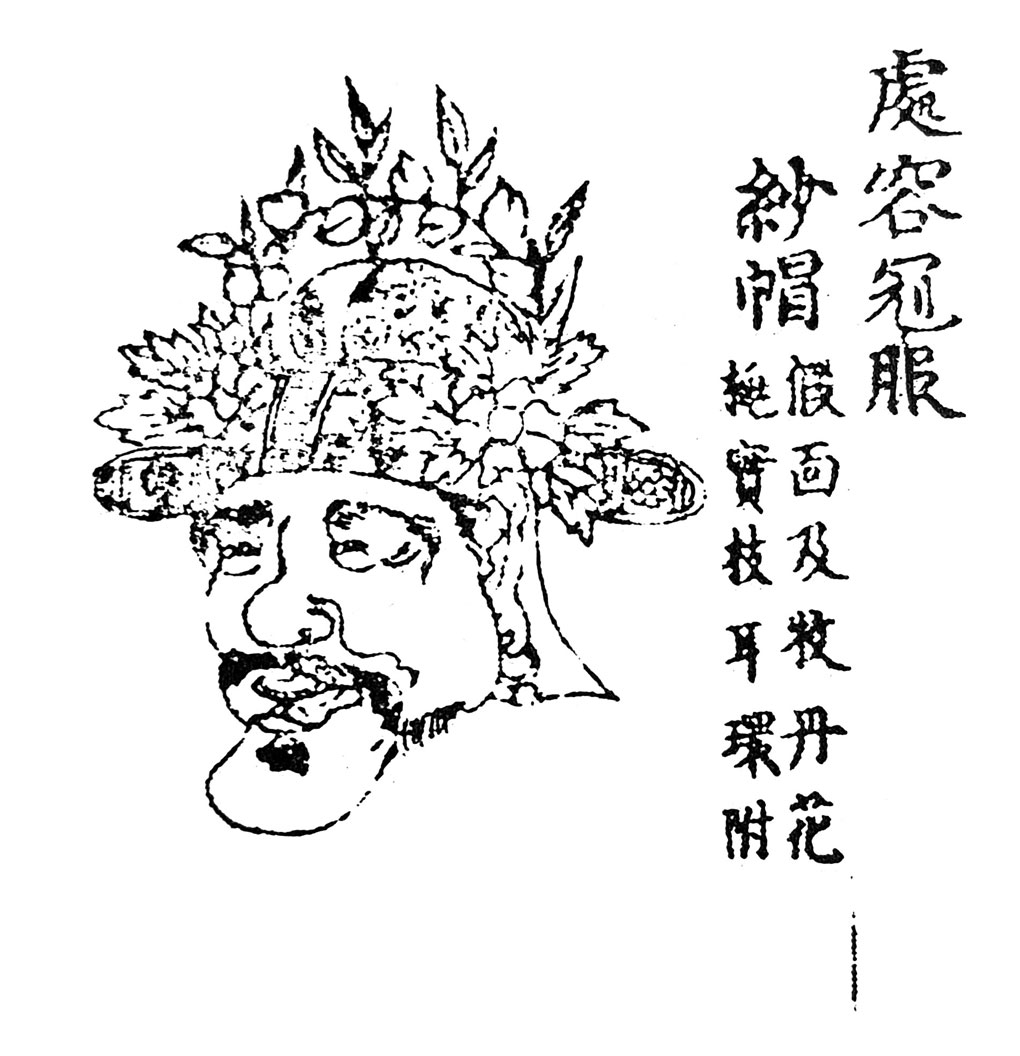

Mask of Cheoyong, son of the Dragon King, wearing a hat decorated with peonies and peaches. Illustrations of the mask and clothing worn in the Dance of Cheoyong are included in Vol. 9 of “Canon of Music” (Akhak gwebeom), published in 1493 by the Royal Music Academy of the Joseon Dynasty.

“Chaekgeori.” 19th century. Ink and color on paper. 45.3 × 32.3 cm. Private collection.Chaekgeori paintings are characteristically replete with auspicious symbols. Books represent success; a watermelon, many sons; a peach, longevity; and the lotus blossom, happiness.

Confucian Virtues

The situation changed remarkably in the 19th century and peonies became the most popular flower in paintings. A gorgeous folding screen covered with depictions of peonies was installed in homes in the hope of turning one’s dwelling into a blissful nest, and was set up at festive occasions as a propitious backdrop to enhance the splendor of the mood.

It seems Confucian scholars adopted a more realistic perspective as the country became entangled in four wars to repel invasions by the Japanese (1592-98) and then the Manchus (1627, 1636-1637). Those who had emphasized solemn virtues and indulged in philosophical debates opened their eyes to more immediate material desires. Joseon society thus joined the “rush for happiness” a step behind, but would eventually wish for happiness more fervently than other East Asian nations.

And yet, minhwa still had some way to go to free itself entirely of Confucian ideology. People continued to pray for happiness within the boundaries of Confucian ethics and folk paintings depicted their wishes for good fortune in a different way. The most conspicuous example is munjado, or ideographic pictures featuring Chinese characters. In other East Asian countries, paintings featuring characters with auspicious meanings, such as happiness, success and longevity, were also popular, but the Confucian ideology of eight virtues – filial piety, fraternity, loyalty, trustworthiness, courtesy, honorability, frugality and sense of shame – continued to be steadfastly upheld in Joseon alone.

Over time, Confucian ideals contained in these pictorial ideographs gradually waned and the iconography of flowers and birds emerged. This had the curious effect of producing paintings that outwardly pursued conventional virtues but were actually profuse with images symbolic of mundane wishes for happiness. Consequently, Confucian ideographic paintings came to assume the complex role of a medium for releasing, rather than repressing, worldly desires for happiness, while ostensibly retaining their traditional symbolism.

Designed to project happiness, minhwa convey a cheerful sentiment with bright colors and humor. They bring joy not only through the symbolic meanings they embody but also through the vivid and flamboyant images themselves.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Joseon faced political and economic challenges. As the Western powers, including Russia, England, France and the United States, encroached on its waters, Joseon gradually faltered and was ultimately annexed by Japan. But strangely, even minhwa from this dire era are cheerful and pleasant, exhibiting few traces of gloom. They epitomize the demeanor of a nation that tried to overcome adversity with a positive attitude: happy paintings arose out of a dark history.

As commerce developed in the 19th century, the demand for paintings expanded in general throughout Joseon society, leading to a broader range of minhwa motifs and s.

“Dragon and Tiger” (detail). 19th century. Ink and color on paper. 98.5 × 59 cm (each). Private collection.The dragon was commonly believed to expel evil spirits. In Buddhism, it was considered a protector of the dharma, or cosmic law and order, which made it a popular decorative motif in temple art. This is part of a two-panel work, the other panel featuring a tiger. The beasts look amusing rather than ferocious.

Cheerful Sensibility

Surprisingly, Joseon folk paintings are now riding the retro trend and becoming popular again. Painting traditional minhwa began as a pastime for women but is now developing into a genuine genre of contemporary art. With the rapid rise in the number of minhwa artists and the consequent evolution of contemporary minhwa, these paintings are enjoying a second heyday.

The main reason for this renaissance is surely the perception that these paintings bring happiness. Though this idea is rooted in magical beliefs, the joyful images emanate a healthy energy that cheers viewers. The most beautiful virtue of minhwa lies in the paintings’ contagious positive energy.

An Architect’s Passion

Any recounting of Korean folk painting inevitably comes around to Zo Za-yong.The man known as “Mr. Tiger” initiated a campaign to rediscover the beauty and value of minhwa, and embarked on a solitary endeavor to introduce them to the world.

Chung Byung-mo Professor, Department of Cultural Assets, Gyeongju University

Considering Zo Za-yong’s education and career, one wonders how he became so absorbed in folk paintings. He went to the United States in 1947 to study civil engineering at Vanderbilt University and later received a master’s degree in architectural engineering at Harvard University.

In 1954, he returned to Korea and participated in many projects to rebuild the country from the ruins of war. There were successes and failures, and along the way, the nation’s cultural heritage grabbed his interest.

At the Beomeo Temple in Busan, Zo was awestruck at how four stone pillars standing in a row supported the ponderous roof of the front-gate structure. That sight inspired frequent trips around the country to study more examples of traditional Korean architecture and to collect roof tiles, a distinguishing feature of premodern buildings. But the pivotal moment in Zo’s discoveries did not happen until 1967 during a trip to Insa-dong, the Seoul district known for its traditional shops and teahouses. The paper used to wrap the rice cake molds he purchased featured the imprint of a tiger and magpie, centerpieces of Korean folk painting.

The painting reminded him of Picasso and he was entranced by the gullibleof the tiger. Following up on the painting, titled “Magpie and Tiger” (Kkachi horangi), Zo realized that it was related to folk beliefs; the tiger is one of the four animals that have been depicted as guardian deities since ancient times. Years later, this same image would become the most iconic Korean folk painting and would even inspire the creation of Hodori, the tiger mascot of the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games.

The next painting that captivated Zo was “Mt. Geumgang” (Geumgangdo). In the painting he discovered Koreans’ view of the universe as well as a unique painting style. Rather than realistically expressing the landscape, the painting features the legendary twelve-thousand soaring peaks, which Zo understood as a representation of the creation of the universe. Within it, he perceived the spirit of minhwa and animism.

“Magpie and Tiger.” Late 19th century. Ink and color on paper. 91.5 × 54.5 cm. Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art.This is the painting that fascinated Zo Za-yong, changing the course of his life. This tiger inspired Hodori, the mascot of the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games.

“Eight-panel Folding Screen with Mt. Geumgang” (detail). Date unknown. Ink and light color on paper. 59.3 × 33.4 cm (each panel). National Folk Museum of Korea.Folk art, as seen in this folding screen with Mt. Geumgang (Diamond Mountains), reflects the unique style of “true-view” landscape painting (jingyeong sansuhwa) initiated by Jeong Seon (1676-1759), a court artist of the Joseon Dynasty. This panel depicts Guryong Pokpo (Nine Dragon Falls).

Pictures of Practicality

Thereafter, Zo devoted his energy to promoting the beauty and value of minhwa in and outside of Korea, planning and organizing 17 exhibitions at home and 12 abroad. His exhibitions and lectures in the United States and Japan are particularly noteworthy. “Treasures from Mt. Geumgang” (East-West Center at Hawaii University; 1976), “Spirit of the Tiger: Folk Art of Korea” (Thomas Burke Memorial Washington State Museum, Seattle; 1980), “The Eye of the Tiger” (Mingei International Museum, San Diego; 1980), “Blue Dragon and White Tiger” (Oakland Museum of California; 1981) and “Guardians of Happiness” (Craft and Folk Art Museum, Los Angeles; 1982) – the titles of these exhibitions underscore the aspects of Korean folk painting that Zo wanted to highlight for overseas audiences. He also produced catalogs related to the exhibitions in English, Japanese and Korean.

Zo’s perspective of minhwa fell outside of mainstream parameters. Instead of regarding the folk paintings as fine art, he placed them in the larger context of life and human nature. Zo’s concept departed from the definition proposed by Yanagi Muneyoshi, Japanese art critic and founder of the folk craft (mingei) movement. Nor did it align with “the art of the people” propounded by William Morris, champion of the Arts and Crafts Movement in England. It was also in conflict with the Korean art history circle, which saw minhwa and court painting as two separate categories.

Zo Za-yong, who studied civil and structural engineering in the United States, was an architect compiling an outstanding portfolio when he fell in love with a tiger painting by a nameless artist. He spent the rest of his life exploring Korean folk art. © Park Bo-ha

Belief in Samsin

Zo’s fascination with and love of folk painting led him to contemplate its spirit. Through minhwa, he explored the origins of Korean art and sought to identify the foundations of the Korean people’s spiritual world that underpinned their culture. Ultimately, he reached the conclusion that everything came down to a shamanic belief in Samsin, the “triple goddess” governing childbirth. Regarding his journey to pursue the roots of Korean culture, he said the following:

“In the process of fumbling around in search of the goblin, the tiger, the mountain god and the tortoise, the culture of my parents began to reveal itself, though faintly. I found the matrix of the culture of our people in what I’ll call minmunhwa, or folk culture.” (Zo Za-yong, “In Search of the Matrix of Korean Culture” [Uri munhwa-ui motae-reul chajaseo], 2000, Ahn Graphics.)

In 2000, Zo realized a long-cherished dream when he opened the “King Goblin, Dragon and Tiger Exhibition for Children” at Daejeon Expo Park. But he succumbed to heart disease during the exhibition and passed away surrounded by his beloved minhwa. In 2013, the Zo Za-yong Memorial Society was founded to honor and carry on his legacy. In his memory, Gahoe Museum has held the Daegal Cultural Festival at Insa Art Center in Insa-dong at the beginning of each year since 2014.

Chung Byung-moProfessor, Department of Cultural Assets, Gyeongju University