“A constant rollercoaster ride and a document of human victory through art and love.” This is how artist Park Re-hyun (1920-1976) described her life. The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art is commemorating the centennial of her birth in an impressive retrospective.

The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Deoksugung Branch is presenting “Park Re-hyun Retrospective: Triple Interpreter” (September 24, 2020-January 3, 2021). The exhibition looks back at Park’s works created over three decades in four parts: figurative paintings of the 1940s and 1950s; records of exhibitions held in tandem with her husband, Kim Ki-chang, and essays offering glimpses of her thoughts; abstract paintings of the 1960s; and prints of the 1970s. The title of the exhibition, “Triple Interpreter,” evokes Park’s role of interpreting for her hearing-impaired husband in Korean, English and lip reading.

Park Re-hyun explored many materials and techniques in her quest to produce paintings that were Korean and modern at the same time. Her trailblazing print works came after ardent effort to create a profound art world of her own.

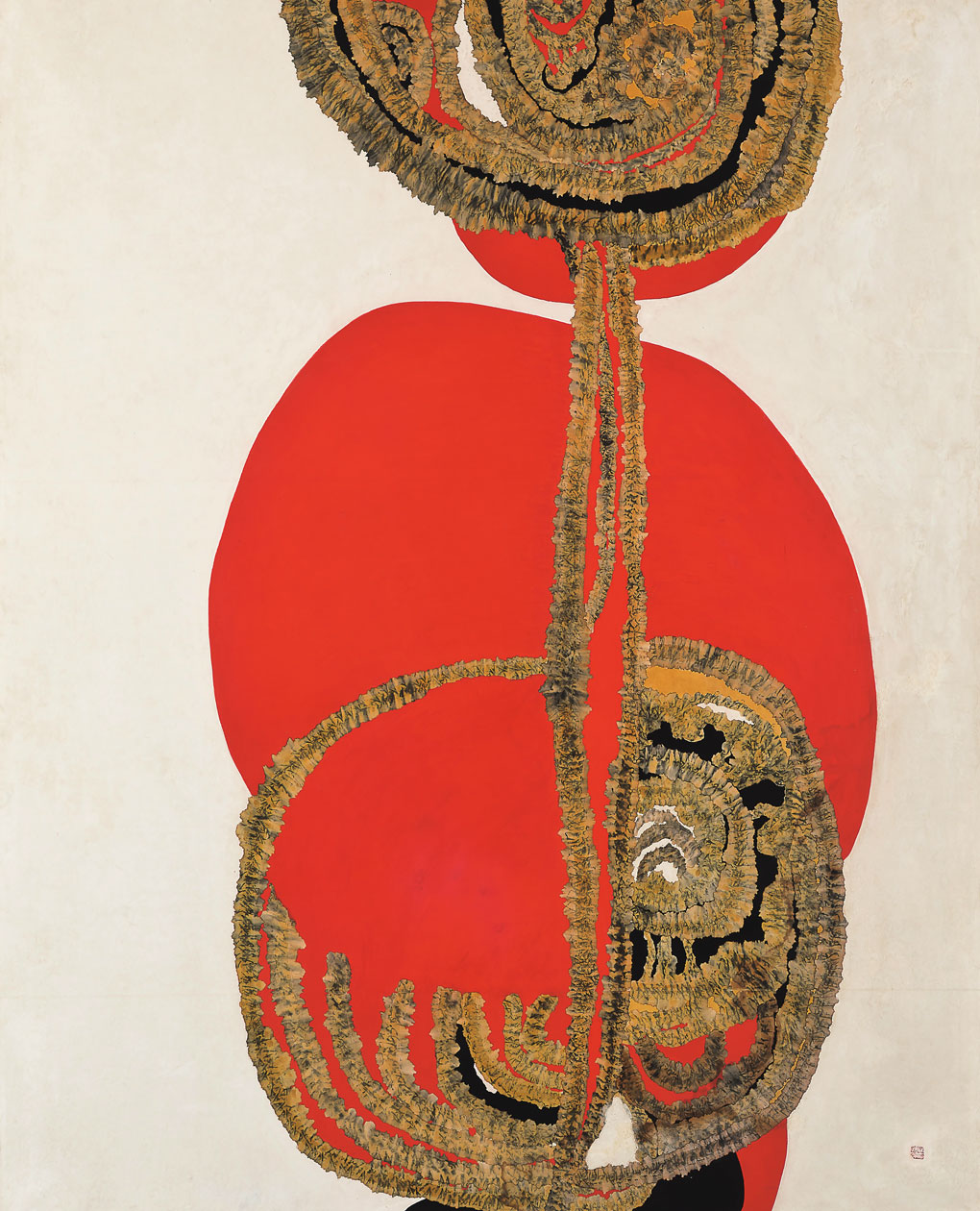

“Work.” 1966-67. Ink and color on paper. 169 × 135 cm. Museum SAN. The work showed that Park had already moved deep into the realm of abstract painting.

Bold Changes

Park Re-hyun started learning art during the Japanese colonial period. While attending Keijo Normal School (later the College of Education of Seoul National University), she studied painting under Japanese art teacher Keishiro Eguchi. In 1940, she entered Women’s School of Fine Arts in Tokyo, around which time she began to seriously pursue a career as an artist. She debuted in 1943 at the 22nd Chosen [Korean] Art Exhibition, winning the Governor-General’s Award for her painting “Makeup.” Depicting a young Japanese girl in a black kimono in front of a red makeup table, the painting shows strong color contrast. While it follows a customary Japanese painting style, the sensual and bold composition can be traced back to Park’s very early work.

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, Park and her husband relocated to Gunsan, where her parents lived. They would move back to Seoul four years later, but until then, the couple was able to devote themselves to their art despite the wartime conditions. As a result, Park would win the Presidential Award in two national exhibitions in 1956, organized by the Ministry of Education and the Korean Fine Arts Association, for “Open Stalls” and “Early Morning,” respectively.

Up until the mid-1950s, Park had mostly painted women, but as she experienced war and life in refuge the women in her paintings grew humbler. Compared to “Makeup,” her postwar works “Open Stalls” and “Early Morning” reveal a huge shift. This is only natural in light of the drastic changes that occurred around her: her country of residence, personal circumstances after marriage and the country’s political situation were all in flux. The most notable change was in her attitude toward art and her painting style.

“I began to think about the convergence of form and color; I thought about the unique unity of the canvas formed by a change in colors; I noticed how sometimes certain lines suggest three-dimensionality.” This passage comes from her essay “Abstract Oriental Painting,” written for a monthly magazine in 1965.

Her thoughts translated into an of objects in a succinct, three-dimensional manner through an appropriate convergence of lines and colors. This new style was already evident in her 1955 work “Sisters.” At first the painting appears to be a simple depiction of two ordinary girls, but a closer look reveals that the older sister’s skin and jacket are the same color, rendered indistinguishable with no clear delineation of which begins where. Nor can one tell where the younger sister’s skirt begins and ends. In traditional Korean painting, ink is primarily used to outline an object, but Park freely applied brush strokes to express outlines as well as coloring.

“Makeup.” 1943. Ink and color on paper. 131 × 154.7 cm. Private collection. This painting earned Park an award at the Chosen [Korean] Art Exhibition while she was attending Women’s School of Fine Arts in Tokyo.

“Open Stalls.” 1956. Ink and color on paper. 267 × 210 cm. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. Park received the Presidential Award at the 1956 National Art Exhibition of Korea for this work which shows a new style influenced by cubism.

Abstract Experiments

The “three-dimensionality” that she mentioned is a reference to cubism, whose influence on the Korean art scene began to be felt in the mid-1950s. Park thought of Picasso as a “versatile artist who always shows the freshness of youth.” She made a print featuring a collage of images from his works and his obituaries from April 1973.

Through the late 1950s, objects in Park’s paintings grew increasingly simple. In January 1960, as a member of the White Sun Group (Baegyanghoe) that had been formed to explore new possibilities for Korean-style ink wash paintings, she visited Taiwan and took part in her first overseas group exhibition, “Korean Contemporary Artists.” The exhibition continued in Tokyo and Osaka, Japan, the following year. Park’s overseas travels led to her realization that contemporary East Asian painters were skeptical about traditional styles, looking for a breakthrough.

The Art Informel movement swept through the Korean art community in the 1960s. Also known as Informalism, meaning unstructured art, the European trend spread after the Second World War in revolt against geometric abstract art. Informalism emphasized lyrical abstraction, focusing on the texture of thick oil paint. Park embraced this trend and at the same time began to create her own canvases, taking advantage of the characteristics of materials used in traditional Korean painting.

This change was evident in the sixth joint exhibition held by Park and her husband in December 1962. In many of her works, objects lost their form, replaced instead by reddish brown masses of color. Her paintings certainly stood out among the works of her contemporary Korean artists who experimented with Informalism mostly by applying rhythmical lines all over their canvases.

Park wrinkled the paper that was her canvas and would sweep an ink brush across it to make stains on the creases. She would also spill pigment on the paper to let it flow and smudge, and later produced the effect of black ink and color paints intermixed. Such experimentation continued until 1963. In 1966, she began to add thin, repeated ink lines in her “Straw Mat Series.” “Work” (1966-67) shows that, while embracing Informalism, Park didn’t use the dynamic lines employed by other Korean artists. Instead, she painted very thin lines on thin but tough traditional Korean paper, letting the ink seep through – a method rooted in the handicraft tradition.

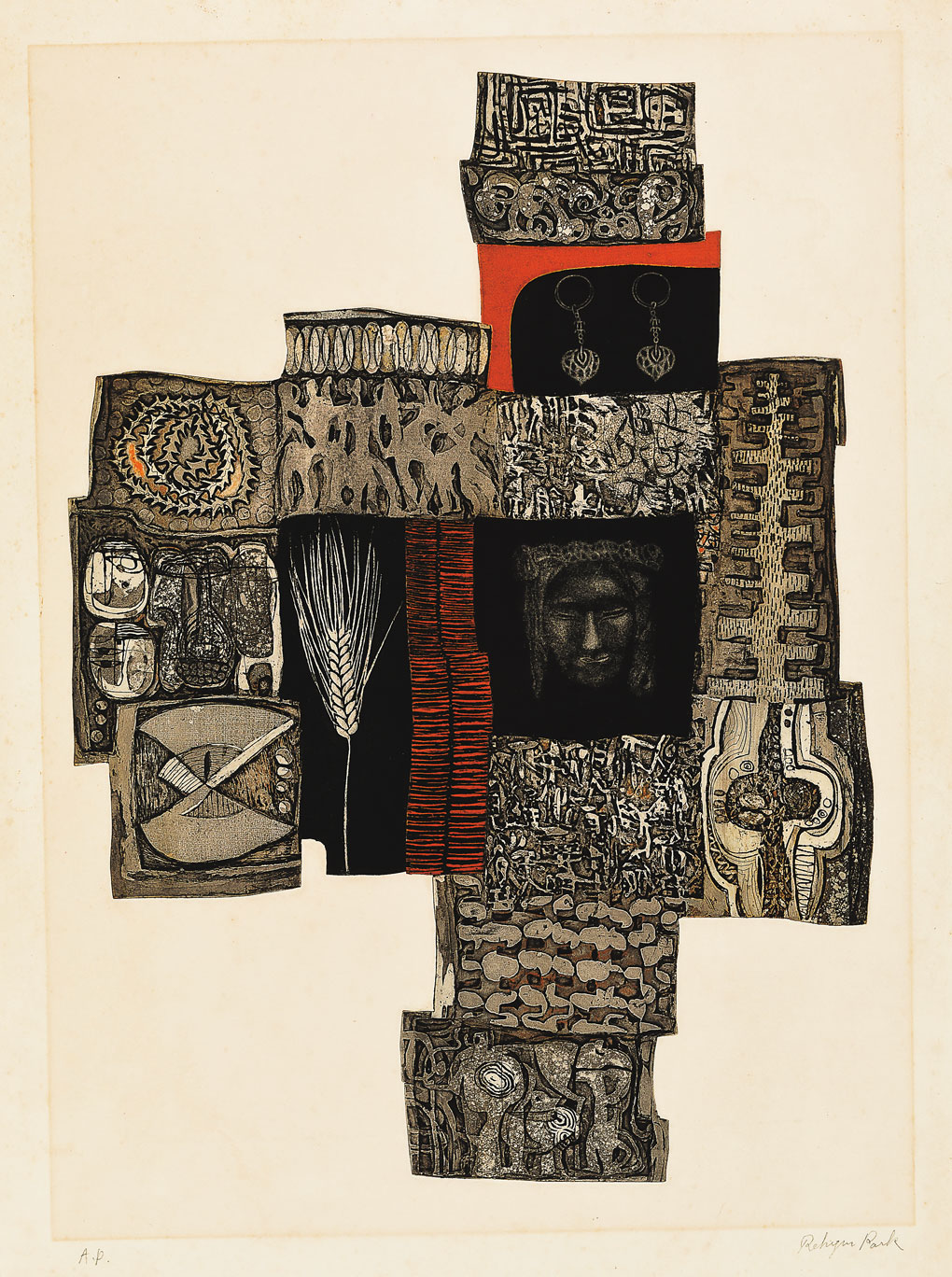

Park’s journey was not over yet. In 1969, she went to New York to study at the Pratt Graphic Art Center and Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop. During the same period, her eldest daughter studied at Pratt Institute. At first, Park mainly used an etching technique to transform her earlier Asian-style paintings into prints. After “Symbol of Joy” (1970-73), she moved on to study the unique characteristics of printmaking and would later create the effect of a raised texture that was readily distinguishable from Asian paintings. Unlike painting, print is a medium that allows an artist to feel firsthand the properties of the material. Thus, Park’s signature touch, fine and detailed, must have shown immediately. The work process probably gave her much joy.

“I began to think about the convergence of form and color; I thought about the unique unity of the canvas formed by a change in colors; I noticed how sometimes certain lines suggest three-dimensionality.”

“Recollection.” 1970-1973. Etching. Aquatint. 60.8 × 44 cm. Private collection. The copperplate print features a diversity of motifs, including the mask of a female character in a traditional masked dance, the womb, grains and ancient gold earrings. Park skillfully expressed her various areas of interest, such as history, life and the earth.

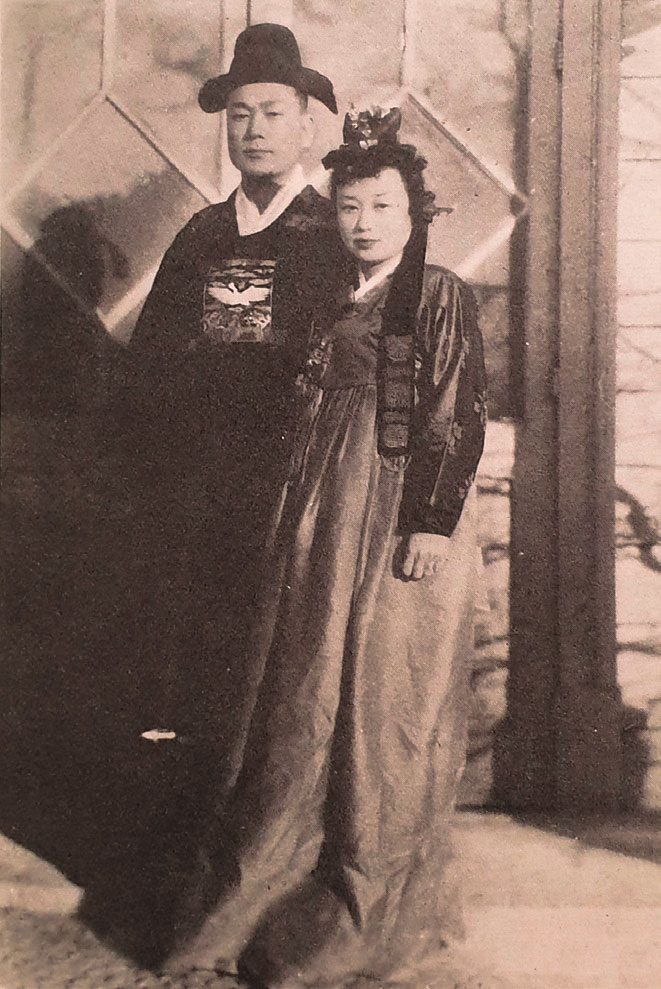

Kim Ki-chang and Park Re-hyun caused a sensation when they married in 1947. Starting the following year, the two artists held a total of 12 joint exhibitions. Kim widened the horizon of Korean painting with his idiosyncratic style encompassing traditional and modern as well as abstract and figurative art.

Time for Repose

Park Re-hyun was an outstanding artist who built her own art world, constantly trying new things over three decades. But she was better known as the “wife of Kim Ki-chang.” Park met Kim in 1943, by which time Kim had already made a name for himself, winning several awards at the annual Chosen Art Exhibition. They married three years later, causing quite a sensation because, in Kim’s own words, he “had very little education and was poor and deaf, whereas she was a landowner’s eldest daughter who had graduated from the best school.”

Park taught her husband lip reading over five years so that he could mimic sounds and communicate on his own. In 1974, when a women’s group awarded her the Shin Saimdang Prize, Park commented that her life was like a rollercoaster ride and a document of human victory through art and love. Art may have been her small, precious niche for peaceful moments – a shelter where she could slip into her own world.