The design was inspired by the intensity of the place. The architect realized that, when observed in the silence of the island at the eastern edge of Korean territory, the movements of the stars, the moon, the sun and the horizon were far more dazzling. What naturally came to mind was a structure resembling a celestial tool that contains cosmic and terrestrial phenomena.

Ulleung Island is 217km from the city of Pohang on the east coast. To the northwest of the island, atop a cliff that plunges into the sea, stands architect Kim Chan-joong’s sensational work Healing Stay Kosmos, achieving exquisite harmony with its natural setting. © Kim Yong-kwan

Getting to Ulleung Island is a bit of a challenge. It takes a full seven hours from Seoul, traveling by train and boat. The tides can get so rough that boats often cannot take to sea, making the island inaccessible for up to 100 days of the year. However, the island’s pristine landscape is well worth the trip. The magnificent rocky mountains overwhelm anyone who first steps foot on the island, giving the feeling that one has transcended time and space.

Mt. Chu, standing 430 meters high on the sea cliff to the northwest of Ulleung Island, is the culmination of this landscape. The flow of the sea and the mountain, the sunset and sunrise, the moon and the stars all look amazing. Healing Stay Kosmos sits on the cliff plunging into the sea. Designed by architect Kim Chan-joong, the resort opened in 2018. There are two wings: Villa Kosmos is a collection of pool villas forming a whirlwind made up of six blades, and Villa Terre is a pension-type building with five vaulted sections lined up to form waves. The UK design magazine Wallpaper* selected Healing Stay Kosmos as Best New Hotel in the 2019 Wallpaper* Design Awards.

Mt. Chu is seen through a 6-meter-tall arched window, which echoes its shape, in a guestroom of Villa Kosmos. The building resembles a whirlwind composed of six blades, each forming a guestroom commanding a different view. © Kim Yong-kwan

Six Different Views

In his quest to create a work assimilated into the natural setting, Kim Chan-joong came upon the idea of utilizing celestial movements. He obtained data from the Korean government’s astronomical observatory computer to plot the trajectory of the sun and the moon, and when he traced their movements on the land they converged in a spiral shape. He added Mt. Chu, the rock on which the sun falls on the summer solstice, the port and the forest to form six major orientation points. As the blades looking outwards to six different views converged in a single circle, they formed a circular building with no directional hierarchy. Hence, Villa Kosmos is a whirlwind orientated to six different views. On the first floor is a communal space, including restaurant and sauna. As you walk up the circular central staircase, it becomes evident that each blade forms one guestroom. Each guestroom door opens to a curved wall and as you walk along the wall a window slowly emerges. It is a huge vertical window at the end of the room that commands a fine view. Its curved arch echoes the shape of Mt. Chu, also known as Ice Pick Peak.

To make the building look more like an object of art, Kim hid most of its main machinery inside the walls so that the building can be perceived as a single space — a single natural organism. From the design stage, the lighting and the heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems and diffusers were embedded, and many mockups were created to bring this to reality. The perforated ceiling lets in wind and light, creating an aesthetic space resembling the hide of a living animal.

More than anything else, the soft and slim curve of the roof and the walls, that are 12cm thick, makes Kosmos an ethereal presence on the land. It’s a wonder that concrete can be that thin and modeled in such a way.

The delicate formative beauty of Kosmos is derived from its material — ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). This new site-cast concrete was first used here on a building. UHPC is characterized by its high intensity, high density and high durability. Even without the steel rebars, steel fiber reinforcement can be used to obtain the necessary intensity. And with such high compressive and tensile strength, very thin structures can be made. Thus, the architect tried out new tectonics for concrete, which up until then had largely been reserved for civil engineering projects.

Villa Kosmos, in the shape of a whirlwind made up of six blades, has curved roof and walls which are only 12cm thick. The new material, ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC), made it possible to create such thin and delicate lines. © Kim Yong-kwan

Challenges with Joys and Pains

The application of UHPC was a challenge and an experiment at every stage of design and construction. The architect’s selection of the new material was based on KEB Hana Bank’s PLACE 1 in Samseong-dong, Seoul, which was designed around the same time. Both PLACE 1 and Healing Stay Kosmos began with the question, “Is thinner and more delicate architecture possible?” A new method was devised after numerous mockups and engineering consultations.

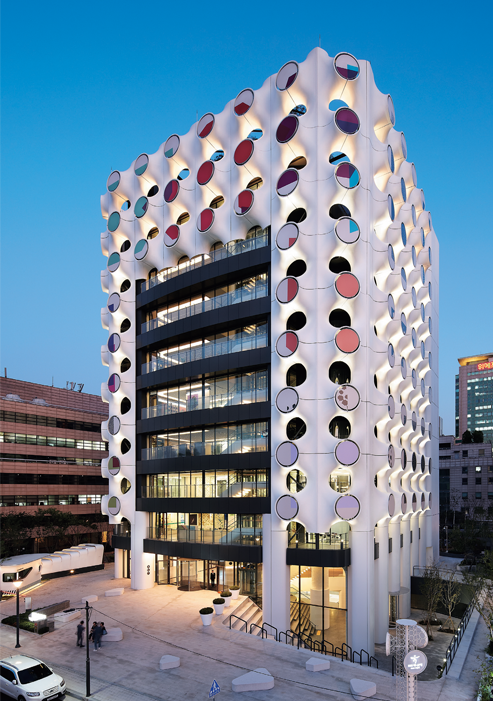

PLACE 1 is a renovated building that integrates many bank branches and offices. The architect built an “open slow core” with cultural spaces on every floor, where people can gather to transform the bank space after it closes at four in the afternoon. A proposal was made to build terraces around the exterior of the building and wrap the exterior in voluptuously curved panels. Each panel is a large modular component measuring four meters square, extruding one meter outward and indenting 50 centimeters inward. The design team was looking for a light material that could be applied to the existing building and was ecstatic when they lighted upon UHPC. But their joy was short-lived for a painful journey lay ahead of them.

The problem was that no precedent existed for casting UHPC inside a mold to create a curvy shape. So, the architect had to lead the entire process, from creating the molds for the modules to ejecting and erecting them. To prove the viability of forming and erecting the UHPC modules, five mockups were made with the engineering team, including the contractor, formwork maker, structural design office and UHPC manufacturer. The process took six long months.

Around the same time, it was decided to make more proactive use of the material on Healing Stay Kosmos as UHPC was deemed the optimal material to create slender and delicate formative beauty. The on-site casting of UHPC, never attempted before, was done by the Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology, which created the unique brand K-UHPC; Steel Life Co. Ltd., which had manufactured 45,000 amorphous exterior panels for Dongdaemun Design Plaza; and the contractor Kolon Global. The architect led the whole process, which involved calculating the intensity of the UHPC, measuring the pressure of the molds, and reviewing on-site casting through many mockups to develop the molds that would be able to create the design, all the while coordinating with the engineering team.

The deciding factor was whether the molds could withstand the significant pressure that would be applied when concrete was poured into them, considering the high density of UHPC, which flows like water. If things went wrong, the molds could break. In addition, in order to construct a three-dimensional amorphous architecture, the molds had to be fixed in a single attempt. On top of that, UHPC had never been applied to the structure of a building. During the three days and two nights when the pouring process took place, everyone held their breaths hoping for the best.

“If tectonics in architecture is about the legitimacy of the relationship between the material and the construction method, I think it is time that the tectonics of concrete also changed.”

Architect Kim Chan-joong is known for his experimentalism in the use of new materials. The System Lab, the architectural firm that he heads, was included in the 2016 Architects’ Directory of the UK design magazine Wallpaper*. © Kim Jan-di, design press

KEB Hana Bank’s PLACE 1, located in Samseong-dong, Seoul, has the nickname “octopus suckers.” The surface features 178 disks with a diameter of two meters each that slowly rotate, accentuating the vibrancy of the building. © Kim Yong-kwan

The Tectonics of Concrete

The drawings of Kim Chan-joong and his company, The System Lab, are always accompanied by a fabrication and construction planning report. The purpose of the report is to think over the construction of the building and seek optimal and rational solutions. Architects cannot indulge in aesthetics alone; they have to research the construction methods fit for their projects and apply the right technology to execute them. The method that Kim Chan-joong calls “industrial craftsmanship” elicits emotional empathy through technological and material innovation.

In his book “Concrete and Culture: A Material History,” Adrian Forty, professor emeritus of architectural history at The Bartlett, University College London, said that concrete is not a material but a process. Concrete was the universal material that gave birth to the International Style of architecture, and we may now come across new types of concrete structures thanks to new methods. In that sense, Kim Chan-joong, in constant search for the optimal solution, is at the forefront of not only architectural design but also of construction process design.

“UHPC is emotionally different from the solid, bulky and heavy structural system of concrete as we know it,” Kim says. “If tectonics in architecture is about the legitimacy of the relationship between the material and the construction method, I think it is time that the tectonics of concrete also changed.”

An architect’s attempt to discover and apply a new material is bound to open up new sensibilities.