The Yun Hyong-keun retrospective runs August 4 through December 16 at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Seoul. Yun Hyong-keun (1928–2007) was a master of dansaekhwa, or Korean monochrome painting.

The exhibition features many of his famous works that translate the aesthetics and style of Korean traditional art into a contemporary vocabulary, as well as materials that reveal his unknown stories.

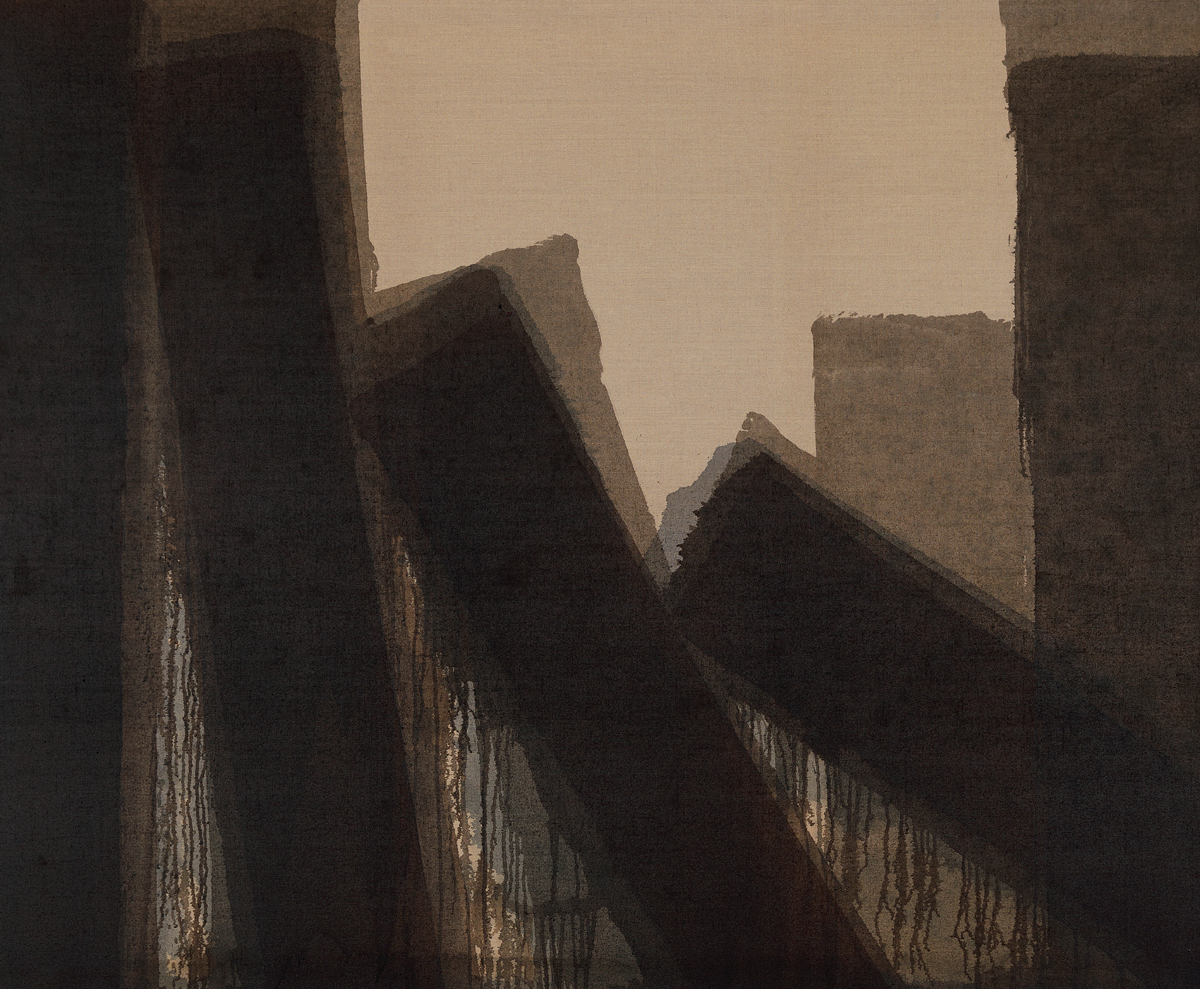

“Burnt Umber.” 1980. Oil on linen, 181.6 × 228.3 cm.

Yun Hyong-keun painted this monochromatic work after hearing about the democratic uprising in Gwangju on May 18, 1980. It represents “people resisting tyranny, leaning against one another, bleeding and falling on the street.” The painting is shown to the public for the first time in this exhibition. © National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

I remember going to the art museum with my parents when I was little. The ambiguous abstract paintings using only one or two achromatic colors were the least interesting. I peeked at the tags, hoping the titles might provide some clues, but I was usually disappointed, and sometimes enraged to find that they read “Untitled” or “Painting No. X.” It was much later that I learned they belonged to a modern Korean art movement, namely the monochrome movement that has garnered global recognition over the past few years.

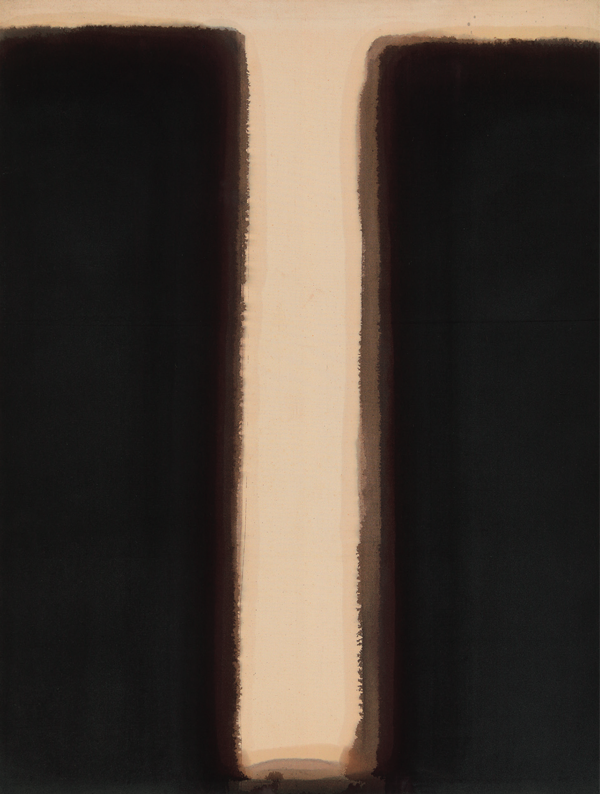

The only painting that I liked back then was one of Yun Hyong-keun’s “Umber-Blue” series. It resembled a black silhouette of columns standing tall against a faint light, either facing westward toward dusk or eastward toward dawn. Strangely, it looked like an ink landscape painting and a Western abstract painting at the same time.

The deep-gray columns seemed to harbor many untold stories. The void, full of either the last light or the first light of day, seemed to transcend the columns and extend toward infinity and eternity. Looking at the painting, I was awed and felt my heart grow bigger. Looking back, that feeling may have been “the sublime” mentioned by British philosopher Edmund Burke: “Infinity has a tendency to fill the mind with that sort of delightful horror, which is the most genuine effect and truest test of the sublime.”

The Color of Ink

The Yun Hyong-keun retrospective at the MMCA brought back memories of that time. I learned some new facts from the curator Kim In-hye, who planned the exhibition. For example, the background colors of dusk and dawn are the original colors of the canvas not covered with primer. The artist considered them to be perfect colors as they were.

From 1973, Yun started using only the color of traditional Korean black ink, or meok, produced by mixing umber and blue, because he wanted to express the sky and the earth with umber as the color of the earth and blue the color of the sky. I also found out that the spread-and-diffuse look resembling ink and wash painting was the result of diluting umber-blue pigment with turpentine and linseed oil.

In a diary entry for January 1977, Yun wrote, “The basic premise of my painting is the gate of heaven and earth. Blue is the color of heaven, while umber is the color of the earth. Thus, I call them ‘heaven and earth,’ with the gate serving as the composition.”

Since heaven and earth are opening through the gate, is this the moment the world was created? It is not that heaven and earth are being divided and opening separately; they are mixed together and separating into two. The light comes through, which has a peculiar effect. (I always believe that the background is not just a void but light.) Art historian Kim Hyeon-suk said that the ink color Yun used was the manifestation of hyeon, a character representing the cosmos in ancient East Asian philosophy. Hyeon means deep, big and distant, and refers to black containing red.

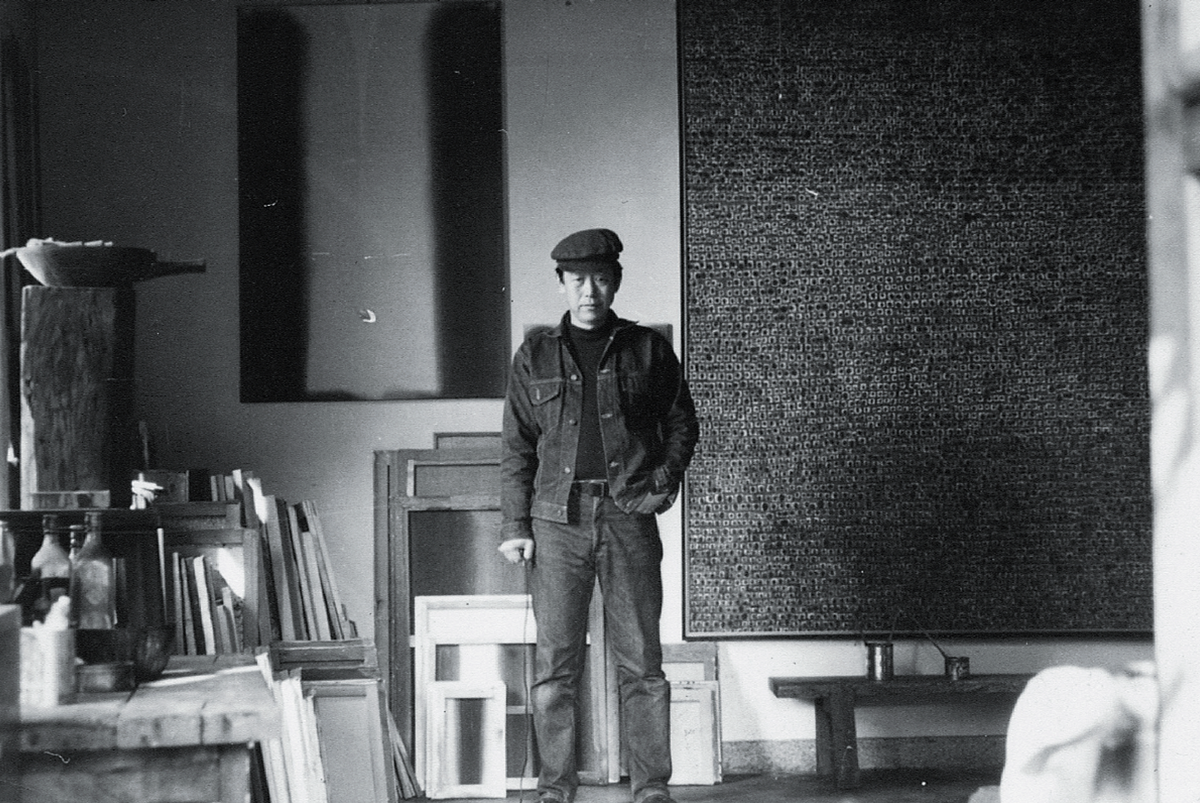

This photo was taken at Yun Hyong-keun’s atelier in Sinchon in 1974, the year his teacher and father-in-law Kim Whanki died. His new work “Umber-Blue” (left) and Kim’s “Where, in What Form, Shall We Meet Again?” hang on the wall side by side.

Rising Above the Teacher

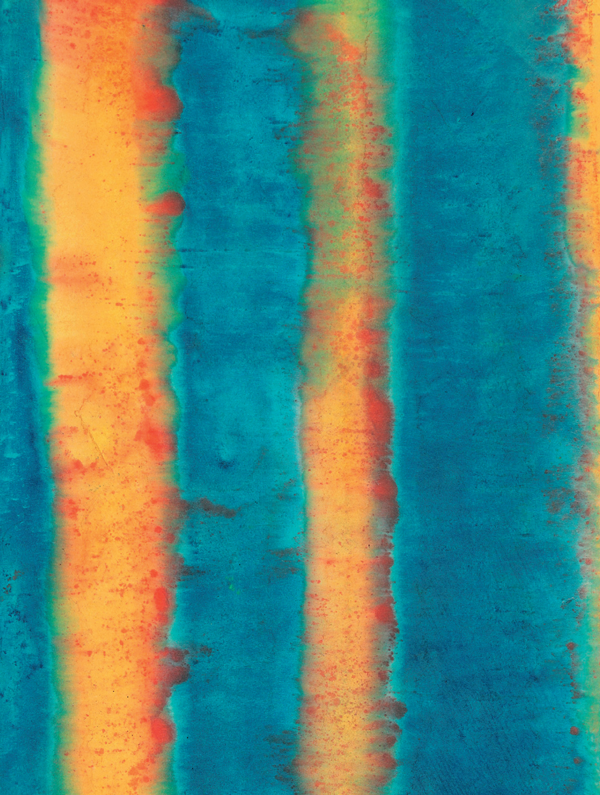

There are other reasons Yun switched to using only umber-blue. He was the student and son-in-law of the famous artist Kim Whanki, whom he respected all his life. But he tried to escape Kim’s influence and create his own art world. Kim was a first-generation Korean abstract painter, inspired by Western abstract art, Korean literati painting and traditional craftwork. He used East Asian motifs such as mountains, clouds, the moon, the “moon jar” and plum blossoms in his half-figurative, half-abstract paintings. After settling in New York in 1963, he turned completely abstract and produced full-canvas dot paintings which resembled star-studded galaxies. Yun’s earlier works certainly show traces of Kim’s influence, especially the drawings using Kim’s hallmark blue.

In October 1974, Yun took a highly meaningful photograph. He hung his new work, “Umber-Blue,” next to Kim’s well-known “Where, in What Form, Shall We Meet Again?” and took up a resolute pose standing in the middle. Curator Kim In-hye said the photo was Yun’s “ambitious documentary, declaring both his start and departure from Kim.”

In explaining his “Umber-Blue” series, Yun wrote in his diary in 1977, “I paint a single wail, with no small talk, going down the two sides of the canvas like thick pillars.” He described Kim’s paintings as “much small talk, as if floating up in the air,” despite his respect for the artist.

Very astute and articulate, indeed. Although both men’s paintings are cosmic, Kim’s blue full-canvas dot paintings invoke poetry and images of a harmonious cosmos, whereas Yun’s paintings are stern, reminding us of primordial chaos in which heaven and earth are intermingled. Color-wise, Kim’s works rise to the sky and float in midair, whereas Yun’s are always rooted to the ground. In the artist’s note for his solo exhibition at Gallery Ueda in Tokyo in 1990, Yun wrote, “Since everything on earth ultimately returns to earth, everything is just a matter of time. When I remember that this also applies to me and my paintings, it all seems so trifling.”

Many people are overwhelmed in front of Rothko’s paintings and shed tears.

Likewise, Yun’s works, which are both abstract and landscapes and a source of agony and joy, have guided my spirit toward shapeless infinity.

Political Persecution

That Yun’s feet were always tied to the ground has to do with his personal history. The black color in his paintings is not only a mixture of the colors of heaven and earth. It is the color of a burnt tree rooted to the earth and the color of burnt hearts belonging to the people whose feet were never able to leave the ground to touch the skies because the absurdities on earth were tying them down. A July 1990 entry in Yun’s diary reads, “I saw the color of a rafter that had burned down. It was much blacker than burnt grass and trees. Perhaps a person’s burnt heart would be the color of that burnt rafter.”

In 1950, during the Korean War, Yun was suspected of being a communist and almost executed. Several incarcerations on political charges followed his near escape from death. The last arrest was a turning point for his art. In 1973, he had been teaching for 10 years at Sookmyung Girls’ High School when he was detained for openly complaining about the school granting admission to an unqualified student. The girl’s father happened to be rich, providing money to the head of the Central Intelligence Agency. Yun was accused of violating the anti-communist law, and the charge brought against him was having a hat like the one Lenin wore. Yun liked the hat he saw in a picture Kim Whanki had sent from New York and so he made one like it on a sewing machine. Little did he dream that the hat would make him a “commie.” He was released a month later but only after signing his resignation letter.

“My paintings took a sudden turn in 1973 when I was released from Seodaemun Prison. Before that I had used colors, but from then on I took a dislike to colors and anything fancy. So my paintings became dark. I spat out vitriol and venom,” said Yun in an interview much later.

“Umber-Blue.” 1976–1977. Oil on cotton, 162.3 × 130.6 cm.

Yun Hyong-keun created this painting after he quit teaching and dedicated himself to art. At the time, Yun mostly worked on the theme “Gate of Heaven and Earth.”

“Drawing.” 1972. Oil on paper, 49 × 33 cm.

One of Yun Hyong-keun’s early drawings in which he experimented with ink dilution and spread on paper. He used bright colors up to this point, which disappeared afterwards.

The message of Yun’s “Umber-Blue” series would be lost on viewers ignorant of his personal history.

His paintings are full of screams, yet silent — “a single wail with no small talk.”

The retrospective includes another very special work related to his personal history — “Burnt Umber,” painted in June 1980. The brushstrokes in the “Umber-Blue” and “Umber” series are always vertical, close to rectangles. In this painting, however, the wide, dark brushstrokes are tilted, almost stumbling over one another, with many thin threads of oil paint rolling down from the wide strokes. They resemble people falling in the street. Yun painted this upon hearing about the massacre in the democratic uprising in Gwangju in May 1980.

He was furious at the repetition of undemocratic political persecution such as he had experienced himself. The monochrome artists of the 1970s and 1980s were criticized for their disinterest in contemporary political and social issues, but from this accusation Yun is definitely exempt. The MMCA purchased “Burnt Umber” from Yun’s family last year and it is being shown to the public for the first time.

It is not in all Yun’s work that black spits anger and venom. “The tree withstands the harsh cold of wind, rain, frost and snow; maintains life; maintains its position; and remains silent,” Yun wrote in his diary. He witnessed and mentioned several times how the tree dies and returns to the earth. His umber-blue black, a color that resembles the fallen tree, is both silence and resistance and also life and death. Borrowing the words of art critic Yi Il, they are a “pristine existence whose shape cannot be defined.”

Toward Shapeless Infinity

Another critic, Oh Gwang-su, called Yun’s paintings “abstract landscapes,” saying that “the landscapes are as simple and rich as can be” and present “nature that is not painted but nature that has formed and come into being on its own.” This is in line with the way U.S. art historian Robert Rosenblum said Mark Rothko’s color field paintings transport the viewers to a sublime landscape, as do the 19th century German romantic landscapes painted by Caspar David Friedrich. However, Rothko did not reproduce scenes from nature like Friedrich; his color fields have become the sublime landscape that guides the viewers’ minds toward shapeless infinity.

Many people are overwhelmed in front of Rothko’s paintings and shed tears. Likewise, Yun’s works, which are both abstract and landscapes and a source of agony and joy, have guided my spirit toward shapeless infinity.