The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art is presenting the exhibition “The Arrival of New Women” from December 21, 2017 to April 1, 2018, at its Deoksu Palace branch. The exhibition explores Korean modernity through images of the “new woman” in the modern visual culture, gaining attention for bringing to light women from a century ago from the perspectives of women today.

The “new woman” refers to women who were cultured through new education during the enlightenment age when Korean society experienced overall transformation under the influence of Western culture. The term, first introduced in Korea in the 1890s, was widely used by magazines, newspapers and other media from the 1920s through the 1930s. The new woman was typically seen as pursuing modern ideologies and culture.

The Iconic Hairstyle

In the summer of 2017, Cho Sun-hee published a novel titled “Three Women,” which features the women revolutionaries Ju Se-juk (1901-1953), Huh Jung-sook (1902-1991) and Go Myeong-ja (1904-?). As like-minded colleagues and friends who led passionate lives during the first half of the 20th century, the three women decided one day to cut their hair. It was a solemn oath as well as a spirited show of camaraderie and solidarity. The novel was inspired by a black-and-white photo published in the monthly magazine Sinyeoseong (“New Woman”), which was popular in Japanese-occupied Seoul. Huh Jung-sook, editor of the magazine and a heroine of the novel, wrote in the special “Short Hair” issue that came out in October 1925: “We were just so happy, as if we had achieved some grand idea or ambition, which had been unknown to us till that day.”

In the 1920s, women with short hair were a sensation. At the time, there were only a handful of them in Korea and the uncommon haircut was seen as a statement, saying: “I am an independent being.” For ages, Korean women had worn their hair in a long pigtail or neat chignon, never undoing it until they went to bed. Wearing short hair itself was an act of bravery and an of strong will. Torn between the traditional values of docility and the modern girl under the yoke of oppression and contradictions, such as imperialism, colonialism, patriarchy, and the clash of Eastern and Western culture, the new woman manifested her identity through her short hair. The first faces that visitors to the ongoing exhibition at Deoksu Palace come across are these short-haired women of 100 years ago.

Section 3 of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s exhibition “The Arrival of New Women” pays homage to five trailblazers from the first half of the 20th century, shedding light on their ideals and frustrations. They are Korea’s first female Western-style painter Na Hye-seok, writer and translator Kim Myeong-sun, modern dancer Choi Seung-hee, socialist feminist Ju Se-juk, and singer Lee Nan-young.

The exhibition comprises more than 500 objects, including paintings, sculptures, embroideries, photographs, printed artworks, films, popular songs, books and magazines. They are divided into three sections, and women with short hair appear in most of them. From the enlightenment age to the Japanese colonial occupation (1910-1945), the short haircut was the iconic symbol of the new woman in modern visual culture. Among the eye-catching exhibits is the cover of the September 1933 issue of the monthly magazine Byeolgeongon (“Another World”) with a special coverage of hobbies. The woman on the cover wears short hair, a top that reveals the curves of her body, a modern-looking skirt that hints at the supple movement of her legs, a provocative red belt, and high heels.

Pre-modern Korean women, especially those of the upper class who were referred to as anbang manim (“madam of the inner room”), were regarded as mere shadows, hidden behind men. They rarely went outside, devoting themselves to household chores and child rearing. However, times changed and the new women roamed the streets. They wanted to become independent beings, learning and working on their own outside the protection of their families. The heroine of Yang Ju-nam’s 1936 film Mimong (“Sweet Dream”) leaves her family, declaring, “I’m not a bird in a cage.”

Characters on the front covers of women’s magazines and novels from the 1920s to the 1940s were mostly portrayed as active, energetic individuals.

Clockwise from left:

“Love Story: Passionate Love,” 1957, published by Sechang Seogwan. Kwon Jinkyu Museum;

Sinyeoseong (“New Woman”), September 1933, illustrated by Ahn Seok-ju, published by Gaebyeoksa. Kwon Jinkyu Museum;

Buin (“Ladies”), July 1922, illustrated by No Su-hyeon, published by Gaebyeoksa. Kwon Jinkyu Museum;

Byeolgeongon (“Another World”), September 1933, illustrated by Ahn Seok-ju, published by Gaebyeoksa. Collection of Oh Yeong-shik

“They were brave enough to stand up against their fate and lead dramatic lives. We get depressed over salaries and promotions, but these women did not concern themselves with such banal issues. They cared little for their own lives and faced history on their own.”

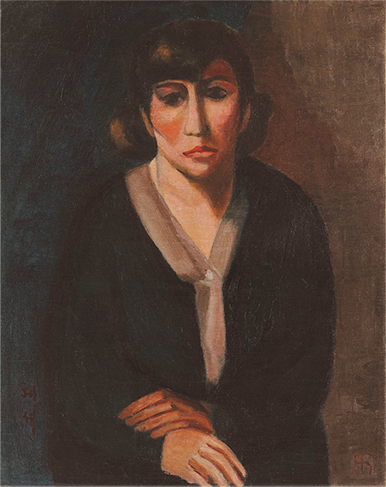

“Self-Portrait” by Na Hye-seok, presumably dated 1928. Oil on canvas, 88 x 75 cm. Suwon IPark Museum of Art

Challenges for the New Woman

The first section of the exhibition, “New Women on Parade,” highlights the dynamism of the new woman walking down the street. In one of the exhibits, Ahn Seok-ju, a pioneer illustrator of serialized newspaper novels, depicts a group of new women through the lively gestures of dancers.

The second section looks back at the new women as artists. Art was considered a means of escape from the education of women in the early modern period, which emphasized traditional virtues such as obedience and quietness. Art provided women with breathing space by combining new values and aesthetic inspirations. However, it was far from easy for women to become artists. The first women in Korea to enter the art scene around 1910 were former gisaeng, or professional entertainers. These women, enjoying relatively more freedom than ordinary women, excelled at calligraphy and painting the Four Gracious Plants (bamboo, chrysanthemums, plum blossoms and orchids), but they were not recognized as independent artists.

The Chosen [Joseon] Art Exhibition, organized by the Japanese government-general, produced Korea’s first-generation women painters, most notably Asian-style painters Park Re-hyun (1920-1976) and Chun Kyung-ja (1924-2015), who had studied art in Japan. Preceding them was yet another famous painter, Na Hye-seok (1896-1948), whose genre was Western oil painting. She was Korea’s first female Western-style painter and writer, but she is best remembered as a feminist and advocate for women’s liberation. She overshadowed her male colleagues not only in art but also in writing, and published many commentaries, novels and essays.

“Self-portrait,” an oil painting presumably dated 1928, expresses in dark colors the pain and depression that a woman artist and intellectual had to go through during those turbulent times.

The third section recalls the ideals of the new women through the lives of five representative figures. It features their images and compares them to the present generation of Korean women, thereby asking how much women have moved forward in the past century.

This part of the exhibition begins with Na Hye-seok. She was the first Korean who graduated from Joshibi University of Art and Design, a private arts school for women in Tokyo. She wrote many essays challenging the traditional patriarchal family and marital system. In one of her most renowned essays, “The Ideal Wife,” which appeared in the third issue of Hakjigwang (“Light of Learning”), a publication of the Korean students’ association in Japan, in December 1914, she accused the male-centered education of women to nurture “good wives and wise mothers” of enslaving women. An excerpt from another essay of hers, “Being Happy Without Forgetting Myself,” published in the August 1924 issue of Sinyeoseong, amounts to an outcry for the recovery of human dignity. She wrote: “We have been too humble. We have lived our lives forgetting that we even exist. We have failed to recognize the unlimited potential hidden in ourselves. It never occurred to us to test them. All we did was sacrifice ourselves and be at someone’s beck and call.”

The rest of the section is devoted to other trailblazers, including writer and translator Kim Myeong-sun (1896-1951), socialist activist Ju Se-juk, modern dancer Choi Seung-hee (1911-1969) and popular singer Lee Nan-young (1916-1965). A slight tremor swept the solemn “Hall of New Women” as the visitors took in the traces of these pioneers.

The third section is all the more interesting as today’s women artists pay homage to the five pioneers in their own ways. The empathy thus generated urges women of the 21st century to awake from their slumber and push ahead with their lives.

“SF Drome: Ju Se-juk” by Kim So-young, 2017. Three-channel video. Artist’s collection

“Research” by Lee You-tae, 1944. Ink and color on rice paper, 212 x 153 cm. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

“One Day Some Time Ago” by Chun Kyung-ja, 1969. Ink and color on paper, 195 x 135 cm. Museum SAN

Homage to the Pioneers

Video artist Kim Se-jin created “The Chronicle of Bad Blood” to honor the first-generation female writer Kim Myeong-sun, who was an illegitimate daughter born to a gisaeng. Her humble origin did not get in the way of her passion for literature, as evidenced by her poems that are recited in the video. Director Kim So-young dedicated her video “SF Drome: Ju Se-juk” to the activist who dreamed of proletarian revolution. Kwon Hye-won’s audiovisual installation “Unknown Song” sheds light on the singer Lee Nan-young whose song “Tears of Mokpo” is as familiar today as ever. The video shows a revolving woman changing her makeup constantly, playing different versions of Lee’s 1939 song “Blue Dreams of Tea Room.”

Cho Sun-hee ends her novel “Three Women” with the statement: “It was in the beginning of the 20th century that these three women were born, but I feel as if I have known them for over 100 years. The times in which they lived were the darkest hours of our history. They literally lived in ‘Hell Joseon.’ It was a hell named Joseon. However, their lives were not simply hell. They were brave enough to stand up against their fate and lead dramatic lives. We get depressed over salaries and promotions, but these women did not concern themselves with such banal issues. They cared little for their own lives and faced history on their own.”

The last sentence rang in my ears as I stepped out of the exhibition hall.

“They faced history on their own.”

Perhaps all the new women featured in the exhibition were like that. How far have we come? I take a bow to our mothers and grandmothers who courageously sacrificed their lives in desperate search of a utopian world. Perhaps the new woman in the true sense has not yet arrived.