The National Museum of Korea recently introduced to the public an outstandinggwaebul from Okcheon Temple in Goseong, South Gyeongsang Province,in an exhibition entitled “Falling in Splendid Grandeur.” The 12th of its kind, the exhibitionopened on April 25, a week before the Buddha’s birthday, and continued until October 22, 2017.Visitors were overwhelmed by the size of the Buddha and bodhisattvas depicted in the hugescroll painting as well as its splendid colors.

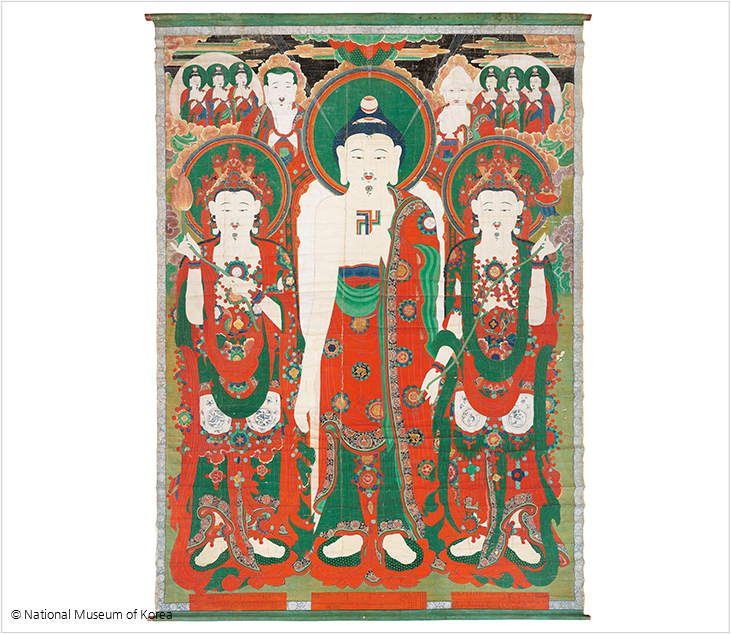

“Scroll Painting of Buddha at Okcheon Temple” (Okcheonsa gwaebul), 1808. Ink and color on silk, 1006 x 747.9 cm.

Designated as Tangible Cultural Heritage No. 299 of South Gyeongsang Province, this huge ritual painting has the unique composition of the Buddha and two bodhisattvas in the center, unlike most other paintings depicting scenes of the historic Buddha’s sermon on Vulture Peak.

The Buddha has an overwhelming presence. Wearing a red monastic robe and surrounded by a round halo, he is facing the world. Flanking the Buddha are two bodhisattvas wearing crowns decorated with flames and holding a cintamani jewel and a lotus bud, respectively. Against the dark night sky, as the lotus flower full of seeds bursts open in its midst, two disciples put their hands together and six little Buddhas encircled in halos descend on a cloud.

What fate brought the Buddha triad, two disciples and six little Buddhas together? Visitors observing the images would direct their attention to the “Record of the Gwaebul Production at Okcheon Temple” (Okcheonsa gwaebul joseong gi), displayed at the bottom of the painting. It says: “A new gwaebul“Scroll Painting of Buddha at Okcheon Temple” (Okcheonsa gwaebul), 1808. Ink and color on silk, 1006 x 747.9 cm.Designated as Tangible Cultural Heritage No. 299 of South Gyeongsang Province, this huge ritual painting has the unique composition of the Buddha and two bodhisattvas in the center, unlike most other paintings depicting scenes of the historic Buddha’s sermon on Vulture Peak.© National Museum of Korea58 KOREANA Winter 2017 KOREAN CULTURE & ARTS 59painting for outdoor rites and ceremonies was created atOkcheon Temple on Mt. Yeonhwa in Jinju County, Right [sic]Gyeongsang Province, in 1808. Plans were made to create anew painting because the old one was destroyed, and the temple’smonks and laymen cooperated in the project.”But producing a huge ritual painting exceeding 10 metersin height was not an easy task. First of all, 20 pok (unit ofwidth) of silk canvas had to be sourced, and red, green andwhite pigments as well as precious gold were necessary. Itrequired donations from 130 individuals in the clergy and laity,made directly or indirectly, to complete the project.

But producing a huge ritual painting exceeding 10 metersin height was not an easy task. First of all, 20 pok (unit ofwidth) of silk canvas had to be sourced, and red, green andwhite pigments as well as precious gold were necessary. Itrequired donations from 130 individuals in the clergy and laity,made directly or indirectly, to complete the project.

In the record, the painting is titled “The Assembly on VulturePeak.” Vulture Peak, or Grdhrakuta, is where the Buddhapreached to a congregation who gathered to hear abouthis enlightenment after six years of meditation as a wanderingascetic. Scenes of this historic assembly have been popular subjectsin Buddhist art through the ages.

However, this particular scroll painting at Okcheon Templedid not include the numerous people gathered to listen to thesermon. A symbolic representation of the assembly was madeinstead by depicting only the Buddha, the bodhisattvas Manjusriand Samantabhadra, the disciples Mahakasyapa and Ananda,and six little Buddhas in awe of the Buddha’s teaching.

Optical Illusion Intended in the Perspective

Measuring 10 meters by 7.5 meters, the scroll could not behung on the wall of a single storey of the museum; instead itoccupied the walls of the second and third floors. Looking upat the painting, it wasn’t difficult to imagine what the ceremoniesmust have been like when it was hung in the temple yard.Gwaebul are large scroll paintings of the Buddha used for outdoorrites and ceremonies. As time passed, their size increasedso that they could be seen from afar, and believers who arrivedat the entrance to the temple grounds were greeted by the sight of a gigantic Buddha soaring to meet the sky.

“Statues of Little Boys,” 1670.Color on stone. Height: 44 cm(left), 47.3 cm (right).The boy monk images weremade in the 17th centurywhen the Hall of Ksitigarbhawas constructed at OkcheonTemple. They supposedlyassist the Ten Kings of Helland judges.

To look at the huge Buddha from the second floor of themuseum, the head had to be tilted quite far back. Looking upfrom the bottom, you could appreciate the perspective andsense of the monk painter Hwaak Pyeongsam, who had an opticalillusion in mind. The main Buddha in the center is paintedlarger than the two bodhisattvas on either side, the disciplesMahakasyapa and Ananda in the upper portion smaller thanthat, and the six little Buddhas even smaller. Viewers are mistakento think there is some distance between the figures on topand the Buddha triad in the center.

From the third floor, you could finally see the figures faceto face. You could notice the round features which are themarks of the Buddha, the fleshy protuberance on the Buddha’scrown denoting his wisdom, the jeweled hair ornament resemblingthe rising sun over the horizon, and the auspicious energyradiating toward the sky. On the chest of the Buddha, whobares one shoulder, a swastika is painted. Lotus flower, dragonand floral scroll designs are embroidered on the Buddha’s redrobe.

Two bodhisattvas flank the Buddha. They are Manjusri and Samantabhadra, associated with wisdom and action, respectively.

They are wearing golden crowns decorated with magnificent flames, and have the face of the Buddha as if they were his son Rahula.

Manjusri is holding a long stem with a wish-fulfillingjewel at the end and Samantabhadra holds a lotus bud in hishand.

The bodhisattvas are adorned with necklaces and braceletsas splendid as the crowns. After feasting amply on the brilliantcolors of red and green, the stories on the bodhisattvas’robes begin to unfold. Rendered in blue paint on white, a rabbitpounds the pestle in a mortar and a squirrel jumps up to snatchsome grapes. A crane with a cintamani in its mouth looks as ifit has come from the immortal world. As such, the story of theBuddha embraces folk tales and legends.

On either side of the Buddha’s head are Mahakasyapa andAnanda with their palms pressed together. Mahakasyapa wasalready an aged monk, and Ananda a young, intelligent one.Regardless of their age, they put their hands together and payrespects to the Buddha triad. Were the six Buddhas in smallhaloes visitors from another world who came to witness thisassembly? Their palms are also pressed together and behind theclouds the night sky spreads, underneath which a lotus flowerblooms.

The historic Buddha, the bodhisattvas Manjusri andSamantabhadra, the disciples Mahakasyapa and Ananda, andthose little Buddhas from another world are brought togetherto complete the imposing pantheon. Coming to the end ofthis magnificent drama, I could see before my eyes the Buddhamanifest as an object of worship. I bowed my head and placed my palms together in reverence.

Then, with my head bowed, my eyes were turned to alarge wooden crate placed at the bottom of the painting. It wasthe storage box for the scroll painting: both the painting andits storage box were on display. Moving both objects togethermust have been a special ceremony of great magnitude. I couldpicture a dozen monks cautiously carrying the scroll carefullytied in ropes out of the main hall of their temple. They wouldhave headed out to a spacious yard where a grand ceremonywas to be held.

Storage Crate with Sun and Moon Engravings

My eyes slowly gleaned over thin metal plates attached tothe surface of the storage box. The metal plate in the middle ofthe box has Sanskrit characters done in openwork. The red coloringof the letters brings life to the otherwise dull wooden box.To either side is a circular metal plate with a Chinese characterengraved on it. Does it mean the sun? Next to the two openworkcharacters meaning “sunlight” is a tree design created inthe repoussé technique. Barely visible, it is reminiscent of thetree in a mural of the Tomb of the Wrestlers (Gakjeochong) ofthe Goguryeo Kingdom. The mythical tree with the sun hangingin it is engraved on the round metal plate.

There is another circular plate broken off in the shape ofa half-moon to show the wooden texture underneath. The twoChinese characters meaning “moonlight” were done in openwork.It was astounding to see this decoration of a gwaebul boxwith images and characters symbolizing the sun and the moon.Who was the artisan? Kindly enough, the inside of the boxrevealed the artists whose names could have gone forgotten:Kim Eop-bal of Jinyang and Kim Yun-pyeong of Cheolseong.Probably metal craftsmen who lived near the temple, their finecraftsmanship brought life to the simple wooden box.

Along with the scroll painting, other treasures of OkcheonTemple made an outing to Seoul. Compared to the 10-meterhighpainting, the figures of the young boys are diminutive,measuring only 44 and 47.3 centimeters tall. Despite their humblesize, they have great significance. In 1670, when the Hallof Ksitigarbha, or the Lord of the Underworld, was built at thetemple, the people of Joseon needed consolation, so many oftheir loved ones having died during the Japanese invasions of1592–1598 and the Manchu invasion of 1636. However miserabletheir lives may have been, and despite their prematuredeaths, the dead deserved a better afterlife. Inside the Hall ofKsitigarbha were enshrined sculpted images of the Ten Kingsof Hell that the deceased were to meet, and the world governedby them was painted in great detail. During the construction,statues of boy monks were also made, carved out of stone and painted.

One hundred years later, in 1777, when the hall was repaired, the boy monk figures were repainted as well. The vivid colors that remain give the images a lively look. The boys that assisted the ten kings and judges have their hair in a long braid and wear long coats with a straight collar. They are holding auspicious birds — phoenix and kalavinka — in their hands. According to the Ksitigarbha Sutra, the boy attendants in hell do not fail to record any small good deed or any evil deed by the deceased. That is why they are called the “boys of good” or the “boys of evil.”

Gwaebul are large paintings of the Buddha used foroutdoor rites and ceremonies. As time passed,their size increased so that they could be seen from afar,and believers who arrived at the entrance to thetemple grounds were greeted by the sight of a giganticBuddha soaring to meet the sky.

“Ten Kings of Hell” (King Yama Series, No. 5), 1744. Ink and color on hemp cloth, 165 x 117 cm.Designated as Treasure No. 1693, the painting depicts scenes of purgatories in the typical 18th-century Joseon style of Buddhist paintings found at Korean temples.

Boy Attendants Accompany the Ritual Painting

Behind the boy monk figures was a depiction of hell from a Buddhist painting. King Yama, wearing a courtiers’ uniform and a tall crown embroidered with sun and moon designs, is seated in a large chair decorated with dragon heads, judging the gravity of the sins of the deceased. He seems to be deep in thought, running his fingers through his beard. Was the deceased a grave sinner?

Colored clouds divide the painting into two parts; the lower part depicts scenes from the purgatories, featuring a karma mirror which reflects all karmic actions of good and evil in the former life of the deceased, and a scribe who keeps record of all sins the deceased had committed. When the souls of dead persons are dragged by their hair in front of the karma mirror, they come face to face with a person holding an ax. This means that they had committed murder in their former life. Other souls waiting their turn are also tied and look up at the karma mirror. The judges and scribes, who accompany King Yama, look at the list of the deceased and write down the sins committed as reflected in the mirror, prior to the king’s judgment. The blank space on the paper means many more sins to record and more judgments left to deliver.

Another work worthy of mention from the exhibition is the “Baekcheon Temple’s Painting of the Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva and the Ten Kings of Hell.” Kept at Yeondaeam, one of the hermitages of Okcheon Temple, it features Ksitigarbha, also known as the Savior from the Torments of Hell, and the Ten Kings and the scribes, who all belong to the netherworld.

According to the record on the painting, it was enshrined in 1737 at Dosol Hermitage of Baekcheon Temple in Sacheon, South Gyeongsang Province, not far from Goseong, where Okcheon Temple is located. Around the 18th century when Okcheon Temple grew in size and influence, the temple’s monks traveled to the nearby areas of Sacheon and Jinju.

This painting indicates the wide range of their activities. It also showcases some superb artistic skills. For example, the monk artist used calm colors and delicate brush strokes, applying ink while the paper was still wet so that some of the facial features of the figures could have a blurred effect. In addition, gilded pigment used on the hand-held tablets and robes of the Ten Kings as well as the sticks held by the judges brings a subtle glimmer to the whole canvas.

Seeing the exhibition on a fine autumn day gave me the chance to contemplate on the resplendent world of the Buddha and the bodhisattvas as depicted in the magnificent scroll painting from the ancient temple, as well as the meaning of enlightenment contained in it.