From the 1930s to the 1950s, Korea was shrouded in poverty. But writers and artists persevered and pursued their dreams, assisted mostly by friends and colleagues. A rare exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Deoksu Palace, Seoul, traces how these creative minds overcame manifold obstacles through camaraderie and cooperation.

“Still Life with a Doll” by Gu Bon-ung (1906-1953). 1937. Oil on canvas. 71.4 × 89.4 cm. Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art.

When academism centered on impressionism was in vogue, Gu Bon-ung was attracted to Fauvism. As suggested by the French art magazine Cahiers d’art in this painting,Gu and his friends appreciated the contemporary art trends of Western countries.

The 1930s was a difficult time in Korean history when Japanese colonial rule grew more oppressive. But it was also a time of modernization and great social change, particularly in Seoul, then called Gyeongseong. Trams and cars ran on paved roads, and luxurious department stores were in business. The streets were swarming with “modern boys” and “modern girls,” who showed off their style in trendy suits or high heels.

With hopelessness about reality coexisting with romantic ideas about the modern times, Gyeongseong was a city of artists and writers as well. They frequented the coffeehouses, called dabang, which had emerged in the downtown area. Creative minds found more than just coffee and tea in these spots. Surrounded by exotic interior decorations and the deep scent of coffee, they discussed the latest trends in the European art scene, such as the avant-garde movement, as Enrico Caruso played in the background.

Coffeehouses and Avant-Garde Art

The poverty and despair of a colonized country could not dampen this creative spirit. The fervor for creativity amid difficult circumstances was underpinned by friendships and collaborations between artists and writers who shared the pain of the times and sought a way forward together.

Today, at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Deoksu Palace, Seoul, the exhibition “Encounters between Korean Art and Literature in the Modern Age” is enjoying considerable public interest for revisiting those years of “paradoxical romanticism.” Despite inconveniences due to social distancing in the COVID pandemic, the exhibition has drawn a steady stream of visitors.

As the title indicates, the exhibition sheds light on how painters, poets and novelists traversed genres and fields, shared ideas and influenced one another to realize their artistic ideals. Introducing the activities of some 50 artists and writers, the exhibition consists of four parts. “Confluence of the Avant-Garde” in Gallery 1 focuses on Jebi (meaning “swallow”), the coffeehouse run by the famous poet, novelist and essayist Yi Sang (1910-1937), and highlights the relationships among the artists and writers who were regulars there. Having trained as an architect, Yi worked as a draftsman in the public works department of the Government-General of Korea for a time, but he quit and set up the coffeehouse when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Known for his surrealist oeuvre, including the short story, “Wings,” and the experimental poem, “Crow’s Eye View,” Yi is one of the pioneers of modern Korean literature of the 1930s.

Jebi didn’t have much to show for itself, other than a self-portrait of Yi and a few paintings by his childhood friend Gu Bon-ung (1906-1953) hanging on the bare walls. Though humble with no remarkable visual attraction, the shop was a favorite hangout of poor artists. Aside from Gu, regulars included novelist Park Tae-won (1910-1986), who was on close terms with Yi, and poet and literary critic Kim Gi-rim (1908-?), to name a few. They huddled together in the coffeehouse, discussing not only art and literature but also the latest trends and works in different media, such as film and music. To them, Jebi was not just a gathering spot but a creative lab where they absorbed knowledge and inspired one another. They were especially interested in Jean Cocteau’s poetry and René Clair’s movies. Yi hung up quotes from Cocteau’spoems, and Park wrote “Conte from a Movie: The Last Billionaire,” a parody of Clair’s satirical piece on fascism, “Le Dernier milliardaire” (1934).

It’s fascinating to see how their works reveal their comradeship and the marks they left on one another’s lives. In Gu’s painting, “Portrait of a Friend” (1935), the man sitting askew is none other than Yi himself. The two were four years apart in age but close friends from their school days. Meanwhile, Kim spared no praise for Gu’s Fauvist style, which broke free from conventions. And when Yi died at the age of 27, Kim mourned his premature death and published the first collection of Yi’s works in 1949. While alive, Yi had designed the cover of Kim’s first poetry anthology, “Weather Chart,” published in 1936. He also did the illustrations for Park’s novella, “A Day in the Life of Kubo the Novelist” (1934), which was serialized in the daily Joseon Jungang Ilbo. Park’s unique literary style and Yi’s surrealist drawings created idiosyncratic pages that were hugely popular with readers.

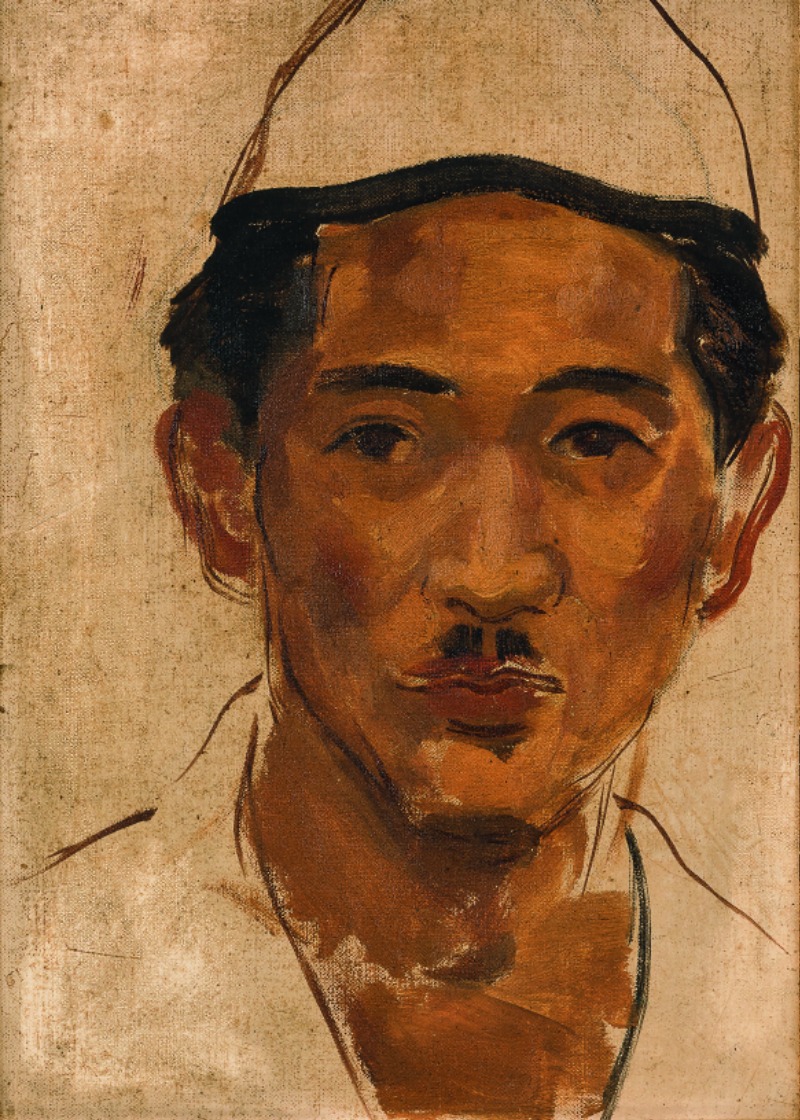

“Self-portrait” by Hwang Sul-jo (1904-1939). 1939. Oil on canvas. 31.5 × 23 cm. Privatecollection.

Hwang Sul-jo, who belonged to the same artists’ group as Gu Bon-ung, accomplished aunique painting style, mastering different genres including still lifes, landscapes and portraits. Thisself-portrait was done the year he died at the age of 35.

Gallery 2 shows printed artworks dating to the 1920s-1940s. On display are books withbeautiful covers as well as magazines carrying the works of illustrators, mostly published by newspapercompanies.

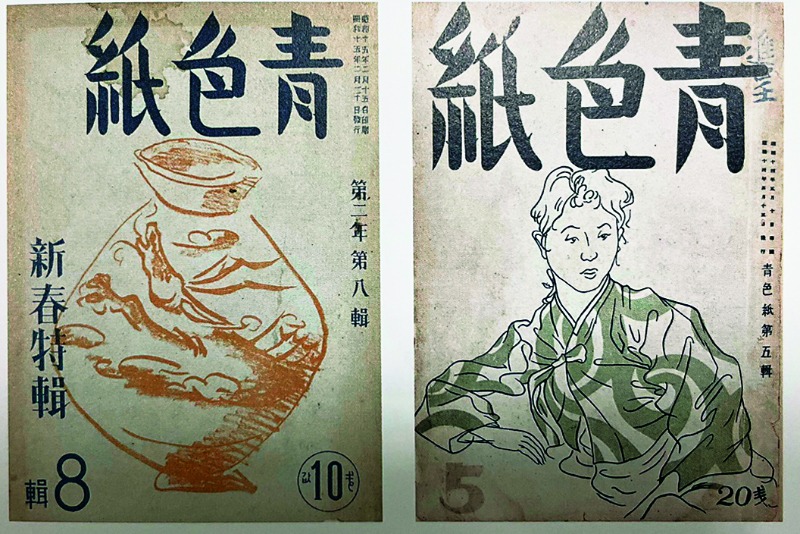

Cheongsaekji (Blue Magazine), Vol. 5, May 1939 (left); Vol. 8, February 1940.

Cheongsaekji, which was first published in June 1938 and ended withits eighth volume in February 1940, was a comprehensive art magazineedited and published by Gu Bon-ung. It covered many fields, includingliterature, theater, film, music and fine arts, and provided quality articlescontributed by famous writers.

Poetry and Painting

Inserting illustrations in serial stories guaranteed a steady income for artists, even if only temporarily, and promoted the image of newspapers as a medium capable of reflecting both popular and artistic tastes. Many of these are featured in Gallery 2, which, resembling a neat library, brings together the achievements of print media, including newspapers, magazines and books, published between the 1920s and 1940s. Titled “A Museum Built from Paper,” this section offers the rare experience of flipping through the installments of serialized novels in newspapers, featuring drawings by 12 illustrators, including Ahn Seok-ju (1901-1950).

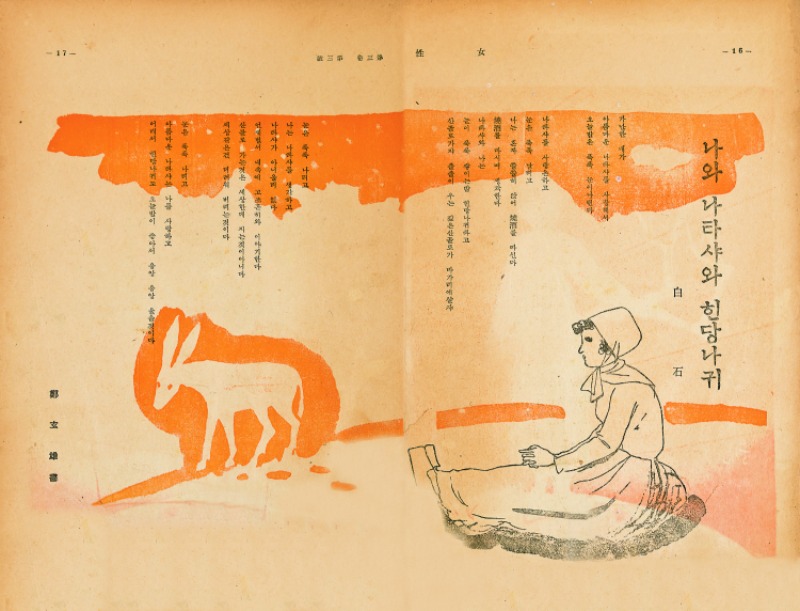

Some newspaper companies also published magazines, giving birth to a genre of illustrated poems called hwamun. “Natasha, the White Donkey, and Me,” a famous poem by Baek Seok (1912-1996), is a noteworthy example dating to 1938. Illustrated by painter Jeong Hyeon-ung (1911-1976), it begins with the lines, “Tonight the snow falls endlessly / because I, a poor man, / love the beautiful Natasha.” The illustration, marked by its orange and white spaces, echoes the tone of Baek’s poem, which describes a peculiar sense of emptiness captured with a vague warmth. The illustrated poem appeared in the literary magazine Yeoseong (Women), which the two men created together to be published by the daily Chosun Ilbo.

Baek wrote many lyric poems with a distinct local color, and Jeong worked actively as an illustrator. Although the two started off as work colleagues, their friendship grew much deeper. From time to time, Jeong would admire Baek seated next to him in the editorial office. In a short piece titled “Mister Baek Seok” (1939), published in another magazine, Munjang (Writing), Jeong praised the poet as being “as beautiful as a sculpture” and drew him immersed in his work. Their friendship continued after they both left Yeoseong; Baek went to Manchuria in 1940 and from there sent a poem titled, “To Jeong Hyeonung – From the Northern Land.” In 1950, after the two Koreas were divided, Jeong went to the North, where he reunited with Baek. He compiled a collection of Baek’s poems, with the back cover of the book featuring his own drawing of the poet, looking older and more mature than in the illustration for “Mister Baek Seok.”

The fervor for creativity amid difficult circumstances was underpinned by friendships and collaborations between artists and writers who shared the pain of thetimes and sought a way forward together.

“Natasha, the White Donkey, and Me” by Baek Seok (1912-1996) and Jeong Hyeon-ung (1911-1976). Adanmungo.This illustrated poem appeared in the March 1938 issue of, a magazine published by the Chosun Ilbo. The collaboration by poet Baek Seok and artist Jeong Hyeon-ungshowcases the frequent exchange between writers and painters mediated by the new hwamun (“illustrated writing”) genre.

“Family of Poet Ku Sang” by Lee Jung-seop (1916-1956). 1955. Pencil and oil on paper. 32 × 49.5 cm. Private collection. Lee Jung-seop, who was staying at poet Ku Sang’s house in the wake of the Korean War, drew Ku’s happy family. At the time, Lee was missing his wife and two sons, who were in Japan.

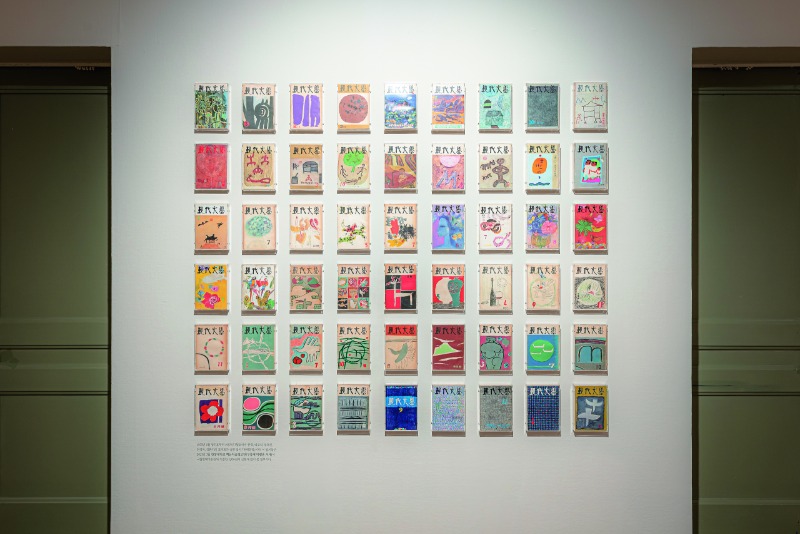

Covers of the magazine, Contemporary Literature (Hyeondae Munhak), which was inaugurated in January 1955. They were illustrated by renowned artists, such as Kim Whanki (1913-1974), Chang Uc-chin (1918-1990) and Chun Kyung-ja (1924-2015), among others.

Writings by Artists

Gallery 3, “Fellowship of Artists and Writers in the Modern Age,” stretches into the 1950s, bringing into the spotlight the personal relationships among the artists and writers of the day. At the center of their personal network was Kim Gi-rim, and his connections expanded beyond his contemporaries to artists of the next generation. Using his profession a a newspaper journalist to advantage, Kim led the initiative of discovering new artists and introducing them to the public through his reviews. This baton was then passed onto Kim Gwang-gyun (1914-1993), a poet and businessman who played a similar role by providing financial support to talented artists. It’s no surprise, then, that quite a few of the exhibits in this gallery come from his personal collection

The one work that probably makes most visitors stop to look is the painting, “Family of Poet Ku Sang,” by Lee Jung-seop (1916-1956). In the piece from 1955, Lee looks upon Ku’s family with envy. Lee had parted with his wife and two sons during the war; he sent them to Japan because the family was enduring extreme financial distress. Though he had hoped to be reunited with them by selling his paintings, the only private exhibition he barely managed to put together failed to bring in the money that he needed. “Family of Poet Ku Sang” is displayed in Gallery 3, along with letters sent to Lee by his Japanese wife, recalling the tragic story of the family and the genius artist’s lonely death in poverty and illness.

The final part of the exhibition in Gallery 4, “Writings and Paintings by Literary Artists,” features six famous artists who were also literary talents. They include Chang Uc-chin (1918-1990), who cherished the beauty of simple and trivial things; Park Ko-suk (1917-2002), whose love of the mountains would last throughout his life; and Chun Kyung-ja (1924-2015), who enjoyed popularity for her colorful painting style and candid personal essays. Also gracing this section are four dot paintings by Kim Whanki (1913-1974). As you approach these paintings and gaze at the microcosmos created by the countless dots that fill the canvas, the names of all the artists and writers you’ve met in the exhibition come back to mind. It seems all the creative talents who shone brightly together in a dark and gloomy period of Korean history have been summoned to gather in one place – at last.

“18-II-72 #221” by Kim Whanki. 1972. Oil on cotton. 49 × 145 cm.Kim Whanki, well-versed in literature and close to many poets, published illustrated essays in various magazines. The lyrical, abstract dot paintings that marked the late period of Kim’s career first appeared in his oeuvre in the mid-1960s, when he was in New York. Early signs of these paintings can be found in the letters he sent to poet Kim Gwang-seop (1906-1977).