Hwang Jai-hyoung has depicted the grim realities of coal miners,rendering scenes of their bleak lives in the blind end with stark realism.As he wanted to break down the boundaries between art and reality by faithfullycapturing the spirit of his times, he went to live among the miners in Taebaek,a remote coal mining town in Gangwon Province.Thus he became a “mining artist,” searching for hope through his paintings.

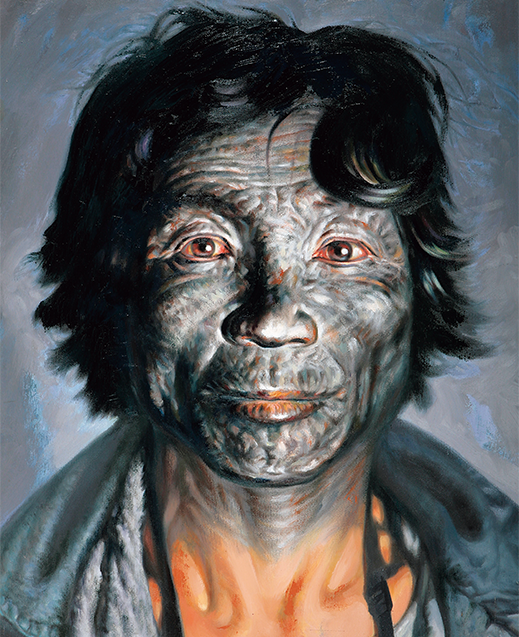

“Portrait of a Miner,” 2002. Oil on canvas, 65 × 53 cm.

Hwang Jai-hyoung’s warm, stocky hands offer a hearty welcome as he thanks me for coming all the way to meet him. I notice his bushy beard and the black overalls and hat he is wearing. Of strong, hefty build, he looks as if he could do the work of two men.They say you can tell a lot about a person from the hands. Just from Hwang’s handshake, I feel as if I already know him. The artist living in the coal mining town is enveloped in somber black, but there’s a sparkle in his eyes. He became a miner himself in order to paint the lives of those toiling underground. “In the blind end, the last hope of life shines like a star,” he says.

“When I came to Taebaek with my family in 1982, it had a dull and dreary atmosphere, like some cheap bar, but I kind of miss those days now,” Hwang says. “This town has gone through certain changes over the past 30 years, pushed around here and there and turned upside down. Having witnessed all of that, I want to tell the story now. Some people ask if it isn’t time I left the place. But I’m not the kind of person who, say, turns my back on a woman once I’m done with her.”

The Blind End, Another Place of Despair

Hwang has sought out the memories of the people and the land, the legacies that should not be forgotten. The Korean word for the blind end in a mining gallery is makjang, which is also used in a negative context, meaning a dead-end situation. To this, he says, “The blind end is where people have lost hope. In that sense, isn’t Seoul more like a coal mine? The suffering and despair of the jobless are not that different from the plight of coal miners.” For several decades, Hwang has been holding exhibitions under the same title, “Dirt to Grasp and Land to Lie On.” It is a metaphor for the people who hold dirt in their hands but have no land in which to lay their bodies, and our times when it has become difficult for people to live a decent life.

“Around the time I graduated from art college, I had a chance to look back on myself. I realized that all those years I had just been posing as an artist, completely oblivious to what was going on in our society,” Hwang recalls. “I thought I had to see for myself and experience firsthand the distorted face of industrialization. I witnessed the lives of socially marginalized workers living on the fringes of the city, in factory districts such as Guro-dong and Garibong-dong. Those driven out even from those places headed to the coal mining towns. I wanted to go beyond the limitations of the Minjung Art [People’s Art] of the 1980s. In a broad sense, the makjang in a mine is a place of despair. In that context, it is a place that is not just found in the mining town of Taebaek but it could be anywhere in Korea, anywhere where there is no hope of leading a decent, dignified life, be it a workplace, the streets, or home.”

He went to Taebaek because he wanted to meet the miners, “who stood for all the people disheartened by the times, but were nevertheless struggling to rise above their circumstances.”

Located in a serene residential area next to the Taebaek Culture and Arts Center, Hwang’s studio has high ceilings that give the place an air of sacredness, like a “sanctuary of paintings.” His workplace is filled with the memories of eating a lunch box in the dark mine under the light of the safety lamp, breathing in the murky air laden with coal dust, and the intensity filling the tunnel, which at times felt like being inside the womb. There are pots of paint stacked against the walls near the doorway. I remember him once saying, “There was a time when I used to buy paint whenever I had some money.” It touches me to imagine the anguish of a poor artist who has such a passion for his work that even while worrying about his next meal, he is thinking of how he can buy paint.

Labor Over Art

“Black Weep,” 1996–2008. Coal and mixed media on canvas, 193.9 × 259.1 cm.

“In my view, the disintegration of activist groups in the 1980s was largely a result of the lack of endurance, and failure to integrate theory and practice,” Hwang says. “When I first set foot in Sabuk in Jeongseon County, Gangwon Province, I knew that I couldn’t remain an onlooker. The miners there didn’t want my art; they wanted my sweat. I dwelled on the question of whether my brushwork carried the same weight as their digging. Resolved to connect with the miners, I organized folk performances and events such as mural painting and producing prints with the locals, and started an art camp. Through painting I cried out that I wanted to stand by them.”

In 1982, Hwang posed as a miner and found work at the Gujeol-ri mine in Jeongseon. Miners were not allowed to work underground if they wore glasses, so Hwang, who had high myopia, had to wear contact lenses all day.

Not long after, he developed acute conjunctivitis because of the coal dust trapped between the eye and the lens. The doctor warned him that he could lose his sight. After three years of working in the mines, he had no choice but to quit, but the people he had met there became the subject of his works. Hwang’s art and his life began to proceed in tandem. From a mere bystander, he was born again as a laborer — a mining artist.

But the miners who were the reason he chose to make Taebaek his second home, and their female colleagues who showed him motherly love and allowed him to put down new roots in the town are slowly disappearing. The power of money and tyranny of capitalism are drying up the soil for their livelihoods. By 2020, all coal mines will be closed down. Tourist attractions are promoted to lure people to the region, but the less fortunate residents have no place to lay their tired bodies. Hwang says there are days when he pushes the canvas aside and drinks soju.

“Meal,” 1985. Oil on canvas, 91 × 117 cm.

He lets out a deep sigh in front of the painting “Mrs. Kwon, the Coal Hewer,” the portrait of a female miner with her face covered in coal dust, her eyes shining all the more brightly.

The paintings piled up in his studio are a testimony and record of his struggles as a mining artist. In “Black Icicles,”Hwang uses mashed coal dust to portray an old miner’s face,deeply lined with wrinkles. The meandering road in “DumundongMountain Pass,” rendered in thick upward strokes of yellowishdirt, is a metaphor for life’s twists and turns. Finding oilpaints too smooth and glossy, he began to use a mix of dirt andcoal dust to achieve a rough texture. He believes this is morelike who we are.

“What prompted me to seriously contemplate the materials I was using was coming face to face with the overalls of minerKim Bong-chun, a casualty of the Hwangji mining accident in1980. His name tag read ‘Hwangji 330.’ All that remained as atestimony to his life and death were his worn-out wrinkled overalls.Nothing could make a better self-portrait,” Hwang says.

The artist boldly uses materials from the ground and everydays found in the coal mining village — such as thedeath certificate of a miner who died of pneumoconiosis, andplywood and wire mesh from an abandoned miner’s house —to honor the memory of a bygone era and the people who areno longer there. Works, such as “Bus,” “Making Briquettes,”“Meal” and “Ambulance,” reveal the self-innovation of an artistwho shared his life’s journey with these laborers.

Hwang has lately become fascinated by a new material:human hair. Huge canvases covered with drawings usinghuman hair as a medium reverberate with a powerful energythat fills his studio. Hair that once used to be on someone’shead now swirls around on the canvas. A single strand of hairmay be fragile, but many strands tangled together becometougher, exuding an energy that overwhelms the viewer. Inthe 150-year history of realism in art, such a solemn, poignantdepiction is probably the first of its kind.

Human Hair as a Medium

Hwang Jai-hyoungsettled in the coal miningtown of Taebaekin 1982, and has sincedevoted himself topainting the wearylives of the miners.

“One day, a teacher came to consult me on family matters.It was about her conflicts with her mother-in-law. I felt a shiverdown my spine the moment I heard her story. After she hadgiven birth, her mother-in-law made her seaweed soup. But asshe was about to take her first spoonful, she discovered a tangleof hair floating in it. The human history of dominance and subordinationoverlapped with the image of the hair in the soup andgave me sudden inspiration. As long as humans exist, it wouldbe impossible to be free from this yoke, I thought,” said Hwang.

Using hair, Hwang has reproduced some of his old works,such as “Portrait of a Miner.” The process of creating a simplesketch and gluing strands of hair onto it seems rather ghastly.“The way the hair s its own flow and rhythm gives megoosebumps,” he says.At first, the artist used his own hair, but as this wasn’tenough, he asked his wife and daughter to donate their hairtoo. “Touching the hair of your loved ones arouses a feeling oftenderness,” Hwang says, clasping his hands. Then he adds, “Ihope these paintings, unprecedented in Western art, will helpestablish my identity as a Korean artist.”

Hwang will unveil his latest works using human hair at asolo exhibition at Gana Art Center in Seoul, scheduled to openon December 14. A fellow artist commented, “This is revolutionary,a shock that pierces my heart.” He will also showcasea new work, the “Vast Silence” series in which the majesty ofLake Baikal is rendered in graphite.

On his long journey insearch of the origins of humankind, Hwang says, he repeatedthe following words to himself over and over again:

“Don’t dwell on small things.”

“Don’t be bound by personal matters.”

The artist, who had once descended to the lowest, darkestplace humans could go, stood in front of the lake that had witnessedthe birth of humankind tens of millions of years ago.Both are the ends of the earth where the light of life is raisedfrom utter darkness. What did he see and draw there? Withmisty eyes like the faces in his paintings “Mother’s Face” and“Father’s Place,” he says, “Life will not be defeated as long asthere is love.”

“I knew that I couldn’t remain an onlooker. The miners there didn’t want my art; they wanted my sweat. I dwelled on the question of whether my brushwork carried the same weight as their digging.”