“Kim Il Sung’s Children,” a documentary film that took 16 years to compile, brings to light a forgotten page from the Korean War – the shipment of thousands of North Korean orphans to communist Eastern Europe to be educated.

In 1952, at the height of the Korean War, thousands of North Korean orphans were hustled onto the Trans-Siberian railroad. After traveling across the Eurasian continent for days, they arrived at the small Romanian town of Siret. There, the excited children stuck their heads out and waved at an assemblage of smiling townspeople who would be their caretakers.

The three-year war orphaned more than 100,000 children. It is well documented that many South Korean orphans became adoptees in the United States or Europe. Far less known is the fate of North Korean war orphans. “Kim Il Sung’s Children,” a documentary film released in June 2020, finally sheds light on those children who were accepted by the Communist Bloc under what is known as a Soviet-orchestrated foster education program.

About 5,000 North Korean war orphans are said to have arrived in five Eastern European countries – Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and Romania – ostensibly to receive an education. In order to unravel the details, Kim Deog-young, the director of the documentary, made more than 50 trips to Eastern Europe over 16 years, beginning in 2004. But this pursuit began with a love story.

Park Chan-wook, a fellow film director, had told Kim about a Romanian woman who was searching for news about her North Korean husband more than 40 years after being separated from him in Pyongyang. The couple were closely linked to the orphans while in Romania.

“It was the first time that I ever learned about North Korean war orphans,” says Kim. Compelled to find out more, he began his long quest to unearth records and tap into old memories.

A North Korean child answers a question at an elementary school in Budapest, Hungary, in the 1950s. Courtesy by Kim Deog-young

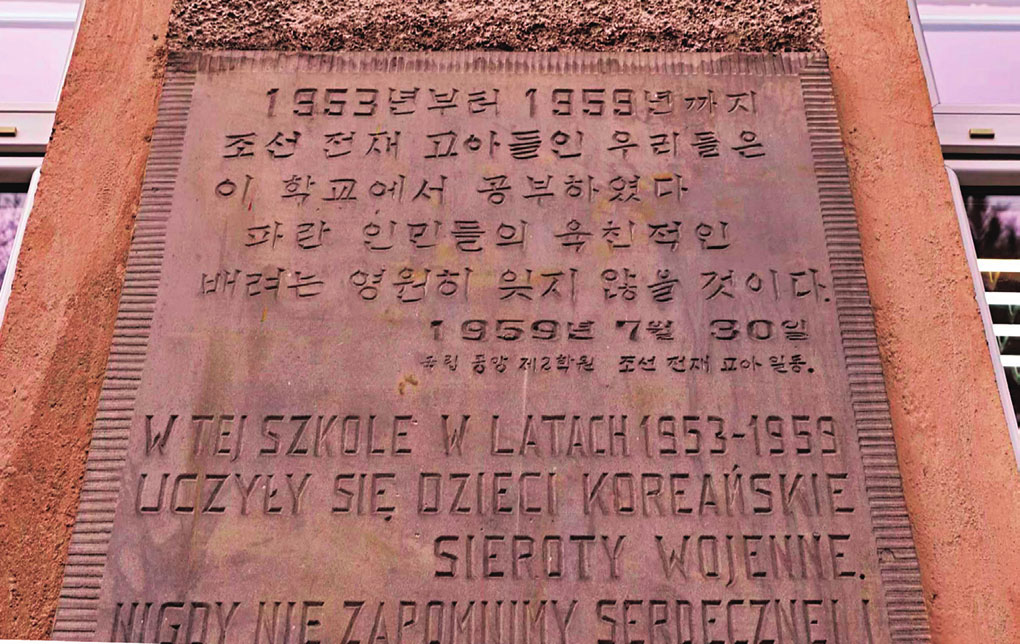

The inscription on the commemorative plaque found at National Central School No. 2 in Plakowice, Poland says that North Korean war orphans studied at the school from 1953 to 1959.

Teacher Couple

Georgeta Mircioiu, 18, had just graduated from a teaching school in 1952. Her first assignment was teaching fine arts at Korean People’s School, an elementary school where North Korean orphans attended classes in Siret, about 100 kilometers from the Romanian capital of Bucharest. The faculty included North Korean Cho Jung-ho, 26. The two teachers fell in love and were married in 1957 after obtaining permission from their respective governments.

Two years later, the North Korean regime suddenly decided to recall all of the children. Cho returned to Pyongyang with his wife and their two-year-old daughter, but soon after their arrival he was purged and sent to a remote coal mine. Mircioiu was left to live alone with their daughter, who suffered from a lack of calcium.

When North Korea adopted its ideology of juche, or self-reliance, it launched a campaign to expel foreigners, even those who were spouses of North Korean citizens. Mircioiu and her daughter had to return to Romania in 1962 and have never been allowed to re-enter North Korea since. In 1967, Mircioiu lost contact with her husband. Today, as she approaches 90, she continues to plead with the North Korean government to tell her at least if her husband is still alive or dead. However, since 1983, all she has received from Pyongyang is a brief message that “he has gone missing.” Mircioiu lives in Bucharest with her 61-year-old daughter and keeps sending letters of appeal to international organizations, anxiously awaiting news of her husband.

Mircioiu still wears a gold wedding band engraved with “Jungho 1957.” She learned Korean to preserve her marital memories and the love that she shared. She has even published a “Romanian-Korean Dictionary” (130,000 entries) and a “Korean-Romanian Dictionary” (160,000 entries). The couple’s heartbreaking story was compiled by Kim Deog-young and aired on KBS TV in 2004, under the title “Mircioiu: My Husband Is Cho Jung-ho,” as a special feature marking the anniversary of the Korean War.

Meanwhile, Kim had continued to follow the trail of North Korean orphans in the five Eastern European countries. He finally hit upon a 4-minute 30-second film from a Romanian film archive. It shows North Korean children getting off a Trans-Siberian train. Kim said that, as soon as Mircioiu saw the film, she called out the names of the children one by one, her eyes filled with tears.

In that moment, it struck Kim that he “should not overlook this history.” He was inspired to do anything possible. It wasn’t easy to locate traces of the North Korean war orphans who had arrived in Eastern Europe in the early 1950s, though he scoured archives, schools and dormitories. And it was nearly impossible to find officials who had served during those years; most had already passed away. But he eventually managed to find people who had spent their childhood together with the North Korean children and recorded their remembrances.

Sudden Farewell

“Kim Il Sung’s Children” shows a vivid black-and-white clip of North Korean children studying and playing together with local kids. It also shows scenes from their group life, getting up at 6:30 every morning to salute a North Korean flag emblazoned with the face of Kim Il-sung and singing “Song of General Kim Il-sung.”

Even now, more than 60 years later, their Romanian and Bulgarian classmates can still sing the song in Korean, which begins, “Each range of Mt. Jangbaek (Paektu) has traces of blood…”

“Back then, we used to play soccer and volleyball on a hill. We were just like real brothers,” Bulgarian Veselin Kolev recalled. He said the North Korean children used to call their teachers “mom” and “dad.”

Dianka Ivanova, one of their teachers, showed an old photo and pointed to one of the children in it, saying, “This is Cha Ki-sun, who liked me the most.”

Kim learned that some children escaped from their dormitory and grew up to settle in nearby areas, marrying local women and becoming taxi drivers. He tried to track them down, but to no avail. The foster education program is known to have been planned by the Soviet Union. It was part of a propaganda campaign to publicize the “superiority” of the communist system and criticize the “consequences of the U.S. intervention in the Korean conflict.”

In 1956, the North Korean children, who were adapting to a new life in a new country, began leaving their friends and teachers. A confluence of events prompted the sudden recall of the children. Resistance movements against the Soviet Union sprang up among Eastern European countries; the so-called “August Faction Incident” in North Korea also occurred that year, an aborted move to remove Kim Il-sung from power while he was visiting Bulgaria; and two North Korean orphans in Poland were caught trying to flee to Austria.

Their days of adapting to a new life and new environment abruptly terminated, the North Korean children said goodbye to their friends and teachers and returned to their homeland in groups between 1956 and 1959.

Before they traveled back to North Korea, some children attempted to leave traces of themselves behind. Steles or obelisks on which their names are carved still stand in forests near their old schools.

Before they traveled back to North Korea, some children attempted to leave traces of themselves behind. Steles or obelisks on which their names are carved still stand in forests near their old schools.

Director Kim Deog-young hopes that his documentary film, “Kim Il Sung’s Children,” will help people around the world have a better understanding of North Korean society.

Georgeta Mircioiu, a Romanian who taught fine arts at Korean People’s School, poses with her North Korean husband Cho Jung-ho. Cho supervised and taught children at the same school.

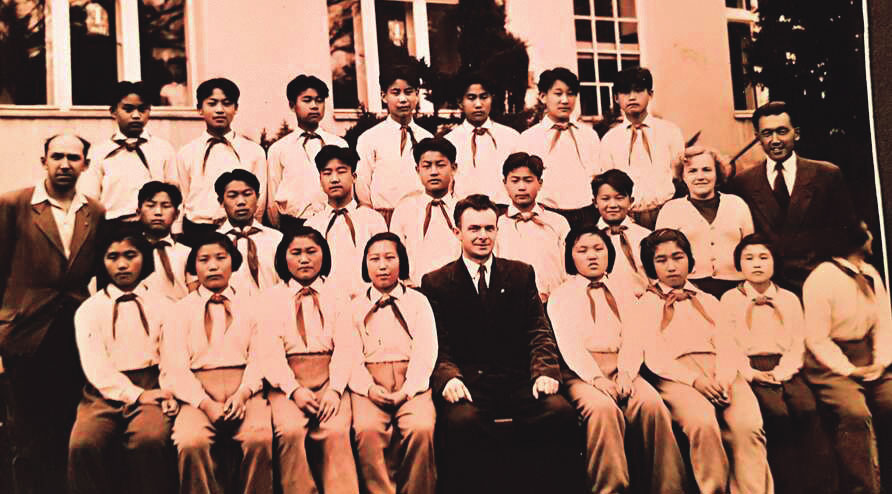

A group photo of children and teachers taken at Kim Il Sung School in Czechoslovakia in the 1950s.

Eastern Europeans still vividly remember their North Korean classmates, with whom they studied and played together more than 60 years ago.

Winds of Chang

The release of “Kim Il Sung’s Children” coincided with the 70th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. The coronavirus lockdown doomed its chances at the box office, but the film has nevertheless reached large audiences in some 130 countries through Netflix with the help of a Korean-American supporter. Despite its failure to attract attention in South Korea, the film has been invited to the main events of 13 international film festivals, including the New York City International Film Festival, the Nice International Film Festival and the Polish International Film Festival, winning significant attention from people around the world.