In his latest book, “Pyongyang Time Flows with Seoul Time,” U.S.-based freelance journalist Jin Chun-kyu presents an atypical view of North Korea based on his encounters with hundreds of North Koreans and revealing pictures. Calling himself a “roving correspondent reporting from Pyongyang,” Jin is devoted to the cultural unification of the divided nation.

Western media often describe North Korea as “reclusive,” a nod to its rigidly controlled accessibility. The limitation naturally inhibits a thorough understanding of its society. Consequently, outsiders are apt to believe that international sanctions are crippling the North’s economy and heaping hardship on its people.

“Pyongyang Time Flows with Seoul Time,” published by Takers in Seoul earlier this year, contradicts this conventional view. Written by Jin Chun-kyu, a U.S.-based freelance journalist, the book unveils an unfamiliar tapestry of today’s Pyongyang, thanks to relaxed restrictions on his visits. Starting in October 2017, Jin visited North Korea four times over the next nine months, staying a total of 40 days. His book, the result of meeting about 250 North Koreans and taking insightful photographs, describes how much the North has changed in recent years. Amid his efforts to unlock relations with Pyongyang, South Korean President Moon Jae-in included the book in his summer vacation reading.

Until the recent thaw, chilly cross-border relations blocked South Korean reporters from entering the North. But Jin has a permanent U.S. resident card, placing him in a different category than other South Koreans, and he has built-up trust with the North Korean authorities. His status allowed him to move around relatively freely, meeting North Koreans at the Masikryong Ski Resort and Mt. Myohyang as well as in Wonsan, Nampo and Pyongyang, and photographing moments of their lives.

Changjon Street in western Pyongyang seen from the Juche Tower. The street lined with high-rise apartment buildings was built in 2012.

© Jin Chun-kyu

Cars and Mobile Phones

Jin calls himself a “roving correspondent reporting from Pyongyang” for a reason. In 1988, he formed The Hankyoreh, a left-leaning South Korean newspaper, along with other journalists who were forced out of mainstream news media by military dictatorships. That year, Jin had a brush with the North when he covered a Military Armistice Commission meeting at the border truce village of Panmunjom. He then visited the North to cover high-level inter-Korean talks in 1992 and the first inter-Korean summit in 2000. At the latter, he photographed President Kim Dae-jung and North Korean leader Kim Jong-il grinning and raising their hands after they signed the June 15 North-South Joint Declaration.

Jin emigrated to the United States in 2001. Sixteen years later, he revisited the North and was dumbstruck by the multitude of cars and proliferation of mobile phones that had transpired.

Taxis were everywhere, or queued up at hotspots. About 10 taxis always stood in front of Okryugwan, waiting for diners to leave the best restaurant in Pyongyang. Contrary to assumptions that only foreigners and senior officials took taxis, ordinary citizens tapped the taxi swarm. Where police officers’ whistles and hand signals were once enough on quiet streets, traffic lights had now become a necessity to maintain order.

Before, such traffic was “unimaginable,” Jin said in an interview. “I heard that more than 6,000 taxis are running around streets in Pyongyang alone and that there are five to six taxi companies there.”

One taxi driver said his cohorts mainly had passengers going to neighborhoods that lacked a subway station or bus stop. More and more people used taxis because they were unable to have a car. Even light traffic jams occurred during rush hours.

Jin’s next big surprise was to learn that as many as five million North Koreans were now using mobile phones, though information and movement were still controlled. Pyongyang pedestrians having a conversation on a mobile phone or taking a picture with it were no longer a novelty.

Another revelation that far exceeded expectations was Internet availability. At Pyongyang International Airport, Jin assumed his connection to a Wi-Fi network was simply a service for global travelers. Later, he discovered unfettered Internet access at his Pyongyang hotel as well. At first, it was hard for him to fathom, guessing that not everyone was allowed to log on.

“It was possible for me to find data I wanted immediately and exchange emails with my acquaintances in the United States and South Korea anytime,” Jin recalled.

His email from Pyongyang to Seoul was met with skepticism; recipients asked, “Is this really an email you sent from the North?” One day Jin waited and waited in vain for a reply to his urgent email to Seoul. He later learned that the recipient doubted that the email was really sent from Pyongyang and feared that he was being watched by somebody. Jin put the finishing touches to “Pyongyang Time Flows with Seoul Time” while in Pyongyang, exchanging emails with the publishing house of his book in Seoul.

“The outside world, including the United States, believes that

North Korea will throw its hands up in the air and surrender soon

if more economic sanctions are imposed. But it occurred to me,

when I took a firsthand look at today’s North Korea,

that such a belief is misguided.”

A long taxi queue picks up passengers after a performance at the Pyongyang Grand Theater. More than 6,000 taxis operate in downtown Pyongyang, according to Jin Chun-kyu, a U.S.-based freelance journalist.

© Jin Chun-kyu

Trusted Outsider

Crisscrossing Pyongyang, Jin came upon streets lined with new high-rise buildings that looked fancier than in the past. Changjon Street is so gorgeous that even foreigners call it “Pyonghattan,” a portmanteau of Pyongyang and Manhattan, or “Little Dubai.” Mirae (Future) Scientists Street, where many scientists live, was so packed with high-rise apartment buildings and a high-end department store that it looked like a backdrop in a capitalist country. A complex of structures in Ryomyong New Town, a development North Korean leader Kim Jong-un reportedly advocated vigorously, was shown by TV cameramen riding along President Moon’s motorcade during his visit to Pyongyang in September.

Jin learned that as many as six pizza parlors occupy the North Korean capital, catering to ordinary citizens, not foreign tourists, and in 2008, the first Italian restaurant opened in Chukjon-dong, Mangyongdae District. When he visited there, Jin found that the spacious 990-square-meter restaurant was packed with customers enjoying pizza or spaghetti.

The rarest pictures that Jin took in Pyongyang show the insides of ordinary citizens’ apartments. A guide told Jin that he was the first outsider to see the insides of Pyongyang residents’ apartments. He visited Ryomyong Street, which is flanked by year-old high-rise buildings staffed with elevator operators. The buildings’ residents are returnees to the neighborhood, who had to relocate when redevelopment began. Most residents there work nearby.

The homes Jin visited were furnished with beds, gas stoves, refrigerators and electric cookers. They resembled middle-income homes in South Korea. Although residents were informed of his visit, Jin did not have the impression that they had installed items that they did not own or decked their homes out purposefully.

North Koreans do not measure their apartments by pyeong (3.3 sq. meters) as done in South Korea, but by the number of rooms. Hence, there are apartments with two to four rooms. The number of family members, not social status and position, determines what apartment they occupy. Each family pays a monthly rent of 240 won (about 2,700 South Korean won) for their home on Ryomyong Street. It may not be a realistic price; it seems to be a symbolic rent, Jin said. North Koreans do not have water bills but are charged for electricity to encourage energy saving.

During his latest visit, Jin was escorted by a guide but did not experience interference. “I was able to freely talk with Pyongyang citizens. Nobody censored the pictures and videos I took,” he said. The North Korean authorities only asked him to photograph statues of (the nation’s founder) Kim Il-sung and (former leader) Kim Jong-il in full length and not to take pictures of construction workers and elderly people in ragged clothes.

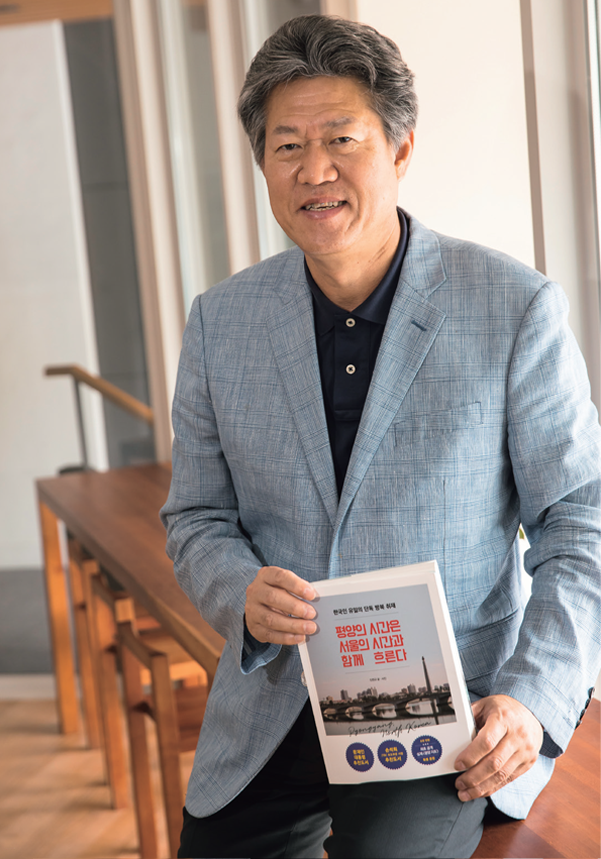

Jin Chun-kyu holds his book, “Pyongyang Time Flows with Seoul Time,” a collection of his impressions of North Korea, which he visited four times from October 2017 to July 2018.

Efforts towards Cultural Unification

Most of the books and pictures about the North published so far are by non-Korean journalists. Not being native Korean speakers, they had to approach the North and its people from the observer’s point of view. Jin, however, was positioned to skirt the linguistic barrier. He wanted to record not only North Koreans’ appearance, but also their emotions and thinking.

“The outside world, including the United States, believes that North Korea will throw its hands up in the air and surrender soon if more economic sanctions are imposed. But it occurred to me, when I took a firsthand look at today’s North Korea, that such a belief is misguided,” he said.

Jin found Pyongyang residents enjoying diverse lives as consumers, far from simply fulfilling their basic needs as outsiders tend to think. Pyongyang people were leading their daily lives “in a calm way, contrary to widespread fears that North Korea was busy preparing for a war,” even in October 2017, when Pyongyang-Washington antagonism intensified over the North’s missile tests and continued development of nuclear weapons.

With a sense of mission, Jin said that he was determined to “see and report on everything without prejudice” as a “border rider.” Some people accuse him of wrongfully using unique aspects of Pyongyang to paint a revisionist portrait of North Korea. He disagrees. “It’s wise to accept it, as it is, as we accept the difference between Seoul and provincial regions, isn’t it?”

While dreaming about becoming a permanent correspondent in Pyongyang, Jin is currently absorbed in creating “Unification TV,” a cable network scheduled to launch in 2019. The content plan includes airing history programs, nature documentaries and food programs that people in the South and the North can enjoy, as well as North Korea-produced programs after obtaining their copyrights.

“I believe that both Koreas can play a big role in moving up the cultural unification of the nation by exchanging diverse cultural contents with each other and restoring homogeneity,” said Jin, who is chairing the Unification TV preparatory committee.