More than 28,000 North Korean defectors have settled in the South after fleeing their home country in a quest for freedom or escape from hunger. Among them are not a few people who had studied art or worked as artists in the North. As the conflict between the two Koreas shows no signs of abating, they express through their work their personal memories of their hometowns and yearning for reunification.

“Take Off Your Clothes and Play” by Sun Mu, 2015, oil on canvas, 130cm x 190cm

At first glance, many of the works by defector artists from North Korea express overt propaganda messages, though the implications are never the same as would be the case if they were back in the North. In fact, Sun Mu, a painter in his mid-forties, had actually experienced the consequences of such a misinterpretation of his art. In 2007, he held the first exhibition of his artworks in South Korea at a gallery in Jongno District, central Seoul. One day, a police officer suddenly burst in and said, “Would you please come with me for some questioning?” He was then escorted to the police station. It turned out that local residents and gallery visitors had reported to the police that his exhibition included “paintings extolling North Korea” — a criminal violation of the country’s national security law. During the Busan Biennale in 2008, his works on display were removed because they depicted the face of Kim Il-sung.

Song Byeok, another defector artist from the North, has gone through a similar experience. His paintings, including works depicting Kim Jong-il and Kim Jongun, were kept at his studio in a shopping mall in Gangnam, southern Seoul. Some elderly men who had seen these works complained to the authorities, which led to a visit by a National Intelligence Service agent.

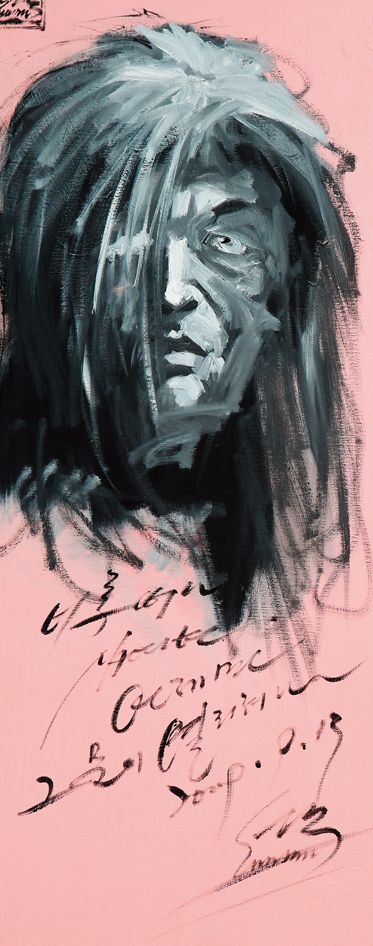

“Self-portrait” by Sun Mu, 2009, oil on canvas,

100cm x 40cm. A note scribbled on the painting says,

“Now it’s about 10 years away from you. I wonder when your door will be opened.”

No Lines, No Borders

Sun Mu slipped out of North Korea in 1998 and arrived in South Korea in 2002, after roaming around China, Thailand, and Laos. He is known as the first North Korean defector artist in the South. Unlike others, he did not flee the North because he disliked the regime. When young, he was a member of the Korean Youth Corps. He attended an art college for three years and served as a propaganda artist in the army. He fled the North by happenstance. He was temporarily working odd jobs for a living in China, when an election day in the North approached. It is mandatory for all citizens in the North to participate in every election. Anyone who fails to vote can be condemned as a political offender and sent to a concentration camp. But he realized it would be impossible for him to return to his home in Hwanghae Province, a region far from the North Korea- China border, in time for the election. Then and there, he decided not to return to the North. In all likelihood, this idea might have been percolating in his mind; he had been impressed by the affluent lifestyle in the South, which he came to learn about in China.

After arriving in Seoul, he enrolled in the College of Fine Arts at Hongik University, where he went on to complete his graduate studies, and became a profes- sional artist. He adopted the pseudonym Sun Mu (“No Line”) as an of his ardent hope that the border between the two Koreas would one day disappear. He never uses his real name or reveals his face in public for fear that his life here would cause harm to his family members in the North.

Sun Mu’s works are characterized by incisive criticism of the North Korean leadership and system. Bright and deceptively cheerful in a kind of pop art style that incorporates elements of North Korean propaganda art, his paintings are implicitly — and undoubtedly — subversive, as exemplified by “Kim Jong-il in Adidas” and “A Jesus in North Korea.”

His sardonic depictions of North Korean reality have caught the attention of international art communities, which has enabled him to stage several solo exhibitions abroad — two in New York, two in Berlin, and one each in Jerusalem, Oslo, and Melbourne. He plans to participate in a group exhibition in France this year. Western media have introduced him as a “faceless artist,” taking note of his works lampooning the leaders he was raised to worship as gods.

‘I Am Sun Mu’

In many of Sun Mu’s recent works, aspects of life in both Koreas, of people and things or events, are depicted side by side, as parallels. This reflects his fervent desire to help bring about peace, reconciliation, and coexistence. He takes a look at the peculiar circumstances of national division and the reality in the North through the lens of artistic inquiry, while keeping a distance from political propaganda. He doesn’t want to fall victim to ideology ever again, he says.

To fully understand Sun Mu’s works, one needs to get beyond simplistic interpretation. This is because he expresses his personal experiences and emotions on canvas while suffering from ideological confusion between two political systems that are poles apart. Although 14 years have passed since he first arrived in the South, he still finds it difficult to adapt to various aspects of his new homeland.

Many a time, he still lives in the North in his dreams, only to awaken and find himself at a loss in his real-life circumstances in the South.

The documentary film “I Am Sun Mu,” which was shown as the opening work for the 7th DMZ International Documentary Film Festival, held in September 2015, offers a glimpse of the kind of person and artist that he is. The 87-minute documentary, produced by American filmmaker Adam Sjoberg, sheds light on his life and work, and what he wants to bring about through art.

The film shows scenes from his aborted exhibition that had been scheduled to be held at a gallery in suburban Beijing in 2014. On the opening day, the Chinese police blocked people from entering the gallery. His artworks, together with a large ad banner, were removed and confiscated, and are still stranded in Beijing. He had intended to convey the Korean people’s desire for national reunification through works rendered mainly in red, white, and blue — the colors of the national flags of the six member countries of the stalled negotiations for North Korea’s nuclear disarmament.

“In the Square” by Sun Mu, 2015, oil on canvas,160cm x 130cm

“I wasn’t going to attend the opening anyway for security reasons. When my exhibition was called off, I was really afraid that I might be taken away, leaving my wife and two daughters behind,” he said.

In spite of many difficulties that he encounters as a marginal man, Sun Mu’s eyes are always looking out toward an open world. “When I visited New York for my exhibition, I realized that there are numerous different countries, including those in the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and Europe, as well as the two Koreas, in the world. I want to create works about the lives of people in those lands,” he said.

‘Take Off Your Clothes’

Song Byeok is another artist whose works satirize the North Korean regime. Like Sun Mu, Song hails from Hwanghae Province. He also uses an alias. But unlike Sun Mu, Song engages openly in public activities, making his face relatively well known.

One of Song’s best-known works is a parody of Kim Jong-il, whose face is superimposed on Marilyn Monroe’s body to replicate the iconic image of her standing over a subway vent, holding down her billowing skirt, in a scene from the 1955 American film “The Seven Year Itch.” Song titled his work “Take Off Your Clothes,” as a message to urge the North to open up.

Pigeons and butterflies often appear in Song’s works, symbolizing the “dreams for freedom hidden deep in the hearts of the North Korean people,” as he explains.

Song painted propaganda posters in North Korea for seven years before fleeing the country to escape from its widespread famine. His first attempt to escape ended in failure in August 2000, when his father drowned in the swift currents of the Tumen River, swollen by heavy rains. Song was apprehended by a border guard. He was sent to a concentration camp, where he lost the tip of the forefinger on his right hand, a vital asset for an artist. After his release, he made another attempt in 2001. He arrived in South Korea via China in 2002. He heard the news of his mother’s death in 2005. Two years later, he succeeded in helping his youngest sister escape the North.

After graduating from the Arts Education Department of Gongju National University in 2007, he enrolled in the graduate school of Hongik University, where he studied Oriental painting. He took on odd jobs for a living, once working for a moving company.

In 2011, he held his first solo exhibition, entitled “Everlasting Escape, Everlasting Freedom,” in Insa-dong, Seoul. He has presented three exhibitions in the United States. His exhibition in Washington, D.C. in 2012 was attended by a number of famous figures, such as Robert King, the U.S. special envoy for North Korean human rights issues, and Kathleen Stephens, former U.S. ambassador to Seoul. The exhibition was covered by major global media networks, like CNN, BBC, and NHK. He has been invited to deliver lectures at vari- ous universities across the United States.

Song Byeok works in his studio.

Song also held an invitational exhibition in Frankfurt in October 2015, during an event to celebrate the 25th anniversary of German reunification, where “Kim Jongun and Marilyn Monroe” attracted media attention, among his other works. He plans to present another exhibition near the former East-West German border in September this year.

Song says he doesn’t merely want to be known as an artist specializing in North Korean themes. He hopes his art can help people around the world, including those in North Korea, who are suffering from hunger and oppression, to hold onto their dreams of peace and happiness. A handwritten note on his studio desk tells of his vision: “Don’t subjugate yourself to reality; don’t stop making challenges but go your own way, patiently and persistently.”

To fully understand Sun Mu’s works, one needs to get beyond simplistic interpretation. Although 14 years have passed since he first arrived in the South, he still finds it difficult to adapt to various aspects of his new homeland. Many a time, he still lives in the North in his dreams, only to awaken and find himself at a loss in his real-life circumstances in the South.

Common Ground through the Arts

Kang Jin-myung, the oldest among the North Korean artists who have settled in the South, was already in poor health when he arrived in Seoul 10 years after he fled the North in 1999. He had long painted propaganda posters for the North Korean regime. After escaping to Qingdao, he worked at an accessory plant operated by a South Korean businessman, by passing himself off as a Korean-Chinese. He was an accomplished artist who had graduated from an art college in Pyongyang and worked as an artist at the Ministry of the People’s Armed Forces, and was a professor as well.

Kang held his first solo exhibition in Insa-dong, Seoul, in February 2010, featuring some 70 artworks that depicted natural landscapes of the two Koreas. But he died of liver cancer the following month, at the age of 57. He had worked hard day and night to prepare for the exhibition, while undergoing treatment for cancer. He often lamented, “I want to dedicate myself to art until our nation is reunified, but my body is too weak to hold out.”

“Back in the North,” he said, “the economy was good during the 1970s and 80s when I began my career as an artist. I received a handsome pay and life wasn’t so tough. But there was no freedom. For an artist, having no creative freedom was tremendously painful.”

The theme of his first and last exhibition was “In Search of the Freedom I Dreamed Of.” His oil painting “Waves of Freedom” testifies to how desperately he craved freedom. He lived under an alias, Kang Ho, for quite a while to avoid retaliation by the North.

Kang’s words reflect his profound desire to see a reunified Korea: “Culture and arts are where the two Koreas can become one, transcending ideologies. I believe we can achieve peaceful reunification a bit earlier if both sides try to approach each other by finding a common ground in the arts.”

“Dreaming of Freedom” by Song Byeok, 2013, acrylic on thick rice paper, 82cm x 110cm