A young Briton’s book of candid photographs and short personal essays illuminates her emotional struggles as a foreign resident in North Korea and challenges common perceptions of the North Koreans.

Lindsey Miller arrived in North Korea with rock-bottom expectations. The 2017-2019 posting of her diplomat husband would mean encounters with heartless, robotic people who would openly exhibit hostility, she thought. Still, undaunted, she grabbed her camera and ventured out of the foreign district in eastern Pyongyang.

Lindsey Miller didn’t plan to write about North Korea, but after leafing through her photographs, she felt compelled to share her experience and visual interpretation. “North Korea: Like Nowhere Else,” a compilation of 200 photographs and 16 essays, was published in London in May 2021.

© Lindsey Miller

Being part of the diplomatic community afforded Miller the advantage of not having a minder who might interfere with her photography. Her early photos were mostly of buildings; she thought their exteriors and designs were exotic. But her attention soon shifted to capturing images of everyday people and learning their stories.

Returning home to the UK and resuming her life as a composer and music director, Miller didn’t intend to produce a book. She says that after two years in North Korea, she feels even less knowledgeable about the country than when she first arrived there. But with her photos stoking memories, she felt compelled to share her encounters. The result is “North Korea: Like Nowhere Else,” a compilation of 200 candid photographs and 16 short essays based on her interactions and arc of emotions while in the North.

“North Korea and the experience I had there are so much bigger and more complex than I could have ever imagined, and it can never be summarized in a simple sentence,” she says. “My book conveys an immersive, sensory experience of what day-to-day life was like for me living as a foreigner in North Korea. It explores the complicated, emotional impact my experience had, but most importantly, it shows how I saw the daily lives of the North Korean people.”

One of her favorite photos is of North Korean soldiers on the move in a truck. It reflects the book’s aim of seeing North Korea not only in terms of amilitary state, but as a place where people lead their daily lives with the same joys, familial love and aspirations that can be found anywhere else.

Young soldiers gaze back at Miller’s camera in one of her favorite photographs. Some ended up waving and blowing a kiss toward her, defying their stonefaced image in the West.

© Lindsey Miller

“My book explores the complicated, emotional impact my experience had, but most importantly, it shows how I saw the daily lives of the North Korean people.”

Interactions

“If we spend more time with the men in the photograph, and knowing the context I detail in the caption, how would our perceptions change and what would that say about us?” Miller asks. The soldiers were in their early 20s. They exchanged greetings with Miller, and one blew her a kiss. Everyone laughed and she blew a kiss to him in return.

In general, Miller found North Koreans to be “very friendly, kind and curious.” But moving beyond spontaneous encounters was usually impossible. As a foreign resident, she wasn’t permitted to visit a North Korean’s home without an escort, and like all foreigners, she owned a local mobile phone that didn’t connect to the telecommunications network used by North Koreans.

“Conversations themselves were frustratingly limiting,” Miller says. “Certain topics had to be avoided because of the risk to the person you were speaking to, and to yourself. And so there you were, two people, stuck in the middle of this controlled cage, trying to balance natural curiosity with careful small talk in an effort to actually get to know each other.”

“It was also difficult developing relationships with Koreans as there was never any clear line between authenticity and falseness in social situations. You never knew if the person you were speaking to was genuinely interested or if they had been tasked with an ulterior motive.”

Despite the hurdles, friendships were formed and so were connections, even if fleeting. “I was once invited to have drinks with some North Korean students,” she recalls. “They asked where I was from while drinking heavily and it felt like I could have been anywhere in the world. Music was playing, students all around were drinking and having a great time. After five minutes they said, ‘We can’t chat long because of security, but it was great to meet you.’ It was moments like that which were precious, and I wish I could have gone on for longer.”

These barriers to interactions meant that questions naturally lingered. For example, why were schoolchildren carrying backpacks emblazoned with Disney characters, cultural symbols of North Korea’s so-called “greatest enemy,” the U.S.?

Questions

In 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump’s Singapore summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un elicited inquiries. Miller had learned about it through international news services, but North Korea’s state media reported it a full day later. Her North Korean acquaintances came and asked questions about what was happening.

“That year brought some much-needed relief, and with the slogan ‘we are one’ being used so frequently, along with seeing Kim Jong-un shaking hands with Donald Trump, it really felt like something had changed, whether that was actually the case or not. My North Korean friends said many times how much lighter they felt,” Miller notes.

Many North Koreans also asked her about British culture but didn’t seem to understand gender equality or same-sex marriage. Questions about South Korea were broached, but they were usually geared toward politics or her personal view of the two Koreas’ future rather than details about life in the South.

Miller’s attention was most drawn to young women in Pyongyang, especially those in their late 20s and early 30s, her own age group. They seemed to value work and their career more than marriage and childbearing. Many asked what it was like to not have children and have a career.

The 2018 North-South pop music concert in Pyongyang was particularly meaningful, given Miller’s career in music. “I felt incredibly privileged to be watching that concert and to see the s on the faces of the audience. It was a moving experience as well for many of the performers, some of whom had family from the North now settled in the South. It was an emotional event and one which I will never forget.”

On a more practical note, North Koreans who attended the pop concert were happy that TV broadcasts included the South Korean song lyrics, Miller says. They struggled to hear the words through the rhythms and lyrical patterns in the South Korean pop songs, which are very different from those in North Korean music.

A huge portrait of Kim Jong-il looms over a subway station in Pyongyang. Images of the late leader are ubiquitous in the North Korean capital.

© Lindsey Miller

Unhurried, elderly North Koreans are seen in front of a worn apartment building. Miller was always curious about what North Korea’s older generations had seen and done, and what their successors would undergo.

© Lindsey Miller

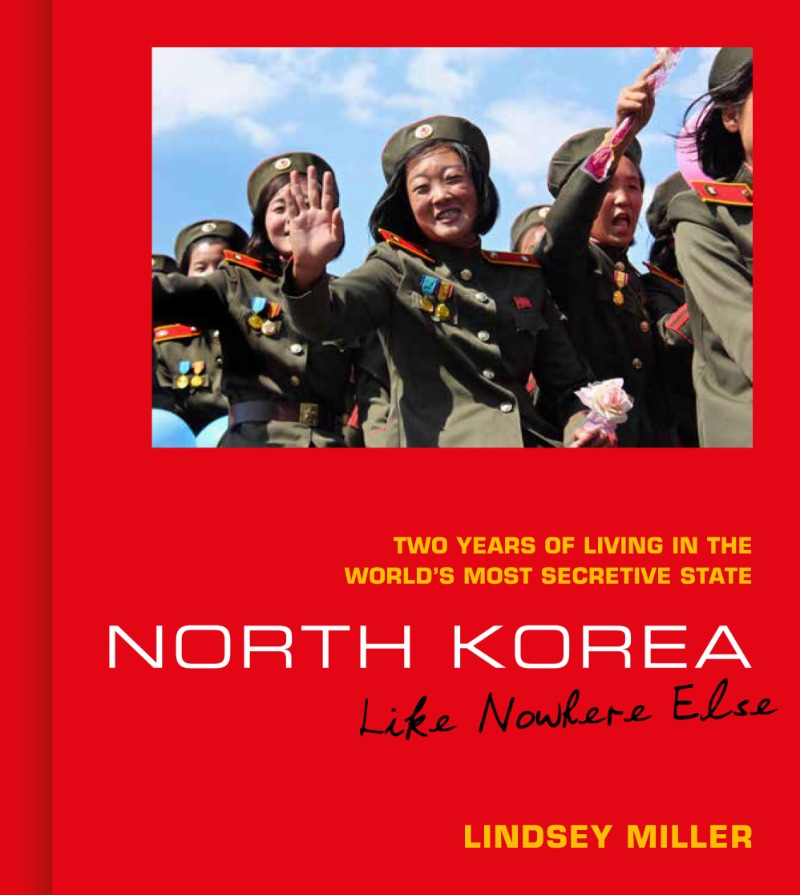

Marching soldiers pausing to give friendly waves grace the cover of Miller’s book, which provokes readers into regarding North Koreans in more approachable terms.

© Lindsey Miller

Outside Again

Miller visited South Korea for the first time after returning to the UK from North Korea. “It was so poignant to visit South Korea after having been to North Korea first, and visiting the DMZ from the South after having visited it from the North was very moving and emotional,” she says.

“What North Korea taught me most was the value of compassion and human connection. In such an isolated place, I was so thankful for the cherished friendships I managed to build with a few North Korean individuals,” Miller says. “In the beginning, I never thought those kinds of friendships would be possible, but I was wrong. It wasn’t easy, but it was possible.”

Those friendships now exist in a vacuum. There is no way to stay in touch – no links through email or telephone – and even if she knew postal addresses, letters and parcels would undoubtedly be intercepted.

“Once you’ve left, it’s like a lifeline has been severed,” Miller says. “Writing this book probably means I won’t be able to go back. But I would want to be able to look my North Korean friends in the eye and know that I was honest in recounting my experiences and the truth of my time there. That I was honest about the lives of the North Korean people and I didn’t sugarcoat the facts because I wanted to go back someday. If we continue to sugarcoat the facts for our own selfish gains, we’ll never discuss the truth of the situation in North Korea. North Korean people deserve better than that.”

“Perhaps with this human focus, we can inspire change in how we speak about North Korea and consider the 25 million people living there in a more personal, connected way. It starts with us,” Miller adds. A Korean edition of her book is scheduled to be published on September 15.