Gasa are traditional Korean poetic songs handed down mostly in the form of scores. Therefore, the first performance of the complete cycle of 12 gasa in 1997 was a groundbreaking event. The singer was Lee Jun-ah, who has devoted herself to the classical vocal music for over 50 years.

Lee Jun-ah, who has devoted herself to traditional Korean vocal music for a half century, says that a profound understanding of all human feelings is necessary to express the lyrics properly. In March this year, she was designated holder of Intangible Cultural Property in the art of singing gasa, traditional poetic songs.

Unfamiliar melodies floated around her childhood home. Lee Jun-ah was always busy, not playing outside with her friends but learning the words of ancient poems. Back then, she would hover around her grandfather, picking up fragments of the seemingly illegible lyrics and moving her body to the gentle, slow tunes that he would sing all day, sometimes with his guests. She liked it as much as playing outside.

Recollecting her childhood, Lee says, “My grandfather, who was a public official, loved singing the poetic songs, sijo, and regularly attended singing sessions. When I was about six years old, his elderly friends from the singing club, sijobang, used to come to our house and take turns singing.” Her mother served tea, and she sat there watching them. With time, she learned the songs and began to sing in front of the guests. “I loved the praises they gave me. And the pocket money, too,” she says.

Her Grandfather’s Consolation

The guests were amazed; the child could sing the old songs that contained difficult words. They wondered who had taught her. She had no proper teacher, though. She just repeated the melodies that she had heard for so long, and memorized the words whose meaning she did not know. If anything served as her teacher, it would have been her own talent and her grandfather’s passion for music. He adored his talented granddaughter, but was strict when training her. Being just a child, she simply reasoned that he loved those songs so much that he wanted her to sing them well. Sometimes she wanted to go out to play, but she followed his rigorous training because his compliments made her happy.

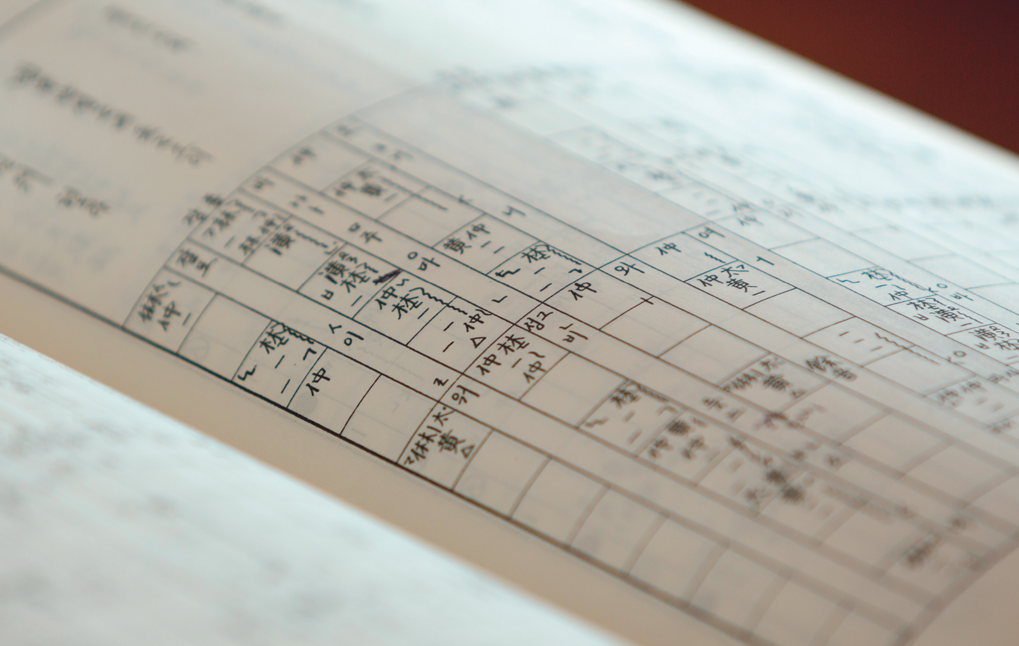

On the gasa scores, the lyrics are written in verse form in the upper part and the pitch and rhythm of each syllable in the grid in the lower part. Of the 12 gasa pieces surviving today, all but three are in sextuple time.

Years had passed when she realized that her grandfather’s preoccupation with her training “had something to do with the violin.” “My grandfather, who loved violin music, raised his eldest son to be a violinist,” Lee says. “I heard that my uncle was an excellent musician. He even formed a trio with cellist Jeon Bong-cho, who later became dean of the College of Music at Seoul National University, and pianist Yun I-sang, the world-renowned composer who went into exile in Germany in the 1970s.”

She came to know that her uncle was in North Korea. They said he was abducted during the Korean War, devastating her grandfather, so the mere sound of the violin greatly saddened him. Lee also learned to play the instrument briefly in her childhood, but her grandfather prevented her from carrying on with it. Eventually, his passion for music found another outlet in sijo singing.br>Her uncle was violinist Lee Gye-seong, who went over to the North during the war and later served as concertmaster of the State Symphony Orchestra there for many years. After all, the sijo songs consoled her family who experienced Korea’s tragic modern history. They also changed the course of life for the young Lee Jun-ah.

Dream of Her Own

Recognizing her talent, Lee’s grandfather searched for a competent teacher. Then, a family acquaintance introduced her to Yi Ju-hwan (1909-1972), who had served as first director of the National Traditional Music Institute, the predecessor of the National Gugak Center. Under the virtuoso singer and teacher, Lee set out on a long, painstaking journey of serious music study. However, life did not go as planned. Yi passed away a few years later, leaving her at a loss for how to continue her study.

In the meantime, she started to participate in monthly concerts of the Korean Jeongak Institute, which specializes in traditional court music. Although the concerts were just given once a month, they were a great burden for an elementary school child who was too young to develop a grand plan for her future. Even at her age, she already took music for granted just like the air, but she had no big dreams about using her musical talent in any way. She was just happy to see others enjoy her singing.

Lee goes on with her recollections: “When things didn’t go as planned, I refused to study music altogether. I entered a regular middle school and focused on schoolwork for three years, just like other kids. I considered going to a regular high school and then major in something other than music at university. Then my grandfather stood firm in his ions. He must have had some foresight. In the end, I decided to enter the Gugak National High School.”

Shortly after Lee entered high school, a teacher who would open her eyes to a new world sought her out - Yi Yang-gyo. With the new teacher, she finally committed herself to learning jeongga, which means “proper songs.” She also came to realize, however vaguely, the significance of what she was doing, and began thinking about how to help revive the genre. Only when she was initiated into the sub-genre of gasa did she finally start to pursue her own dream.

The Final Choice

The Gugak National High School introduces jeongga on its website, roughly as follows:

“Jeongga, meaning ‘proper songs,’ are a genre of traditional Korean vocal music, sung and enjoyed by the literati of the Joseon Dynasty. It is divided into gagok, sijo and gasa. Unlike pansoriand minyo (folk songs), which plainly deal with all sorts of human emotions, this elegant vocal genre is characterized by a rigorous control of emotions. Gagok are the most relaxing in tempo and most refined among them, with poetry and music tastefully blended toa peaceful and profound realm of art. With a five-line structure, gagok were the songs of professional singers accompanied by a small-scale orchestra, while sijo, based on three-line poems, were so widespread that amateurs could sing them to the rhythm of their hands slapping their knees. Lastly, gasa have long verses and are sung to set rhythms.”

Unlike pansori and minyo, relatively well known to the public, jeongga expressing the lofty spirit of Confucian scholars, or seonbi, were, and still are, a major that few students choose. Lee Jun-ah was no exception, for she entered high school to major in the geomungo, a traditional Korean zither. Later, when she entered Chugye University for the Arts and then graduate school at Ewha Womans University, it seemed that she had no choice but to continue majoring in the instrument. But things changed, though gradually, while she was pursuing her undergraduate and graduate studies.

“I’ve done research on the 12 gasa songs, appreciating the beauty and uniqueness of each, and refined my performance of them for 40 years. Doing so, I realized that the universe is ruled by yin and yang, just as there is no joy without sadness.”

Gasa were different from the songs she had long been singing. There was something special and demanding about them. She also found it hard to empathize with the unfamiliar ancient Chinese tales alluded to in the songs. For example, “White Seagull Song” (Baekgu-sa) describes a man rambling in nature appreciating the spring scenery, after being abandoned by the king and ousted from public service; and “Mt. Suyang Song” (Suyangsan-ga) is about a man disheartened as his plan for a leisurely outing to eat and drink under the moonlight was thwarted by wind and snow. The themes of those songs, in a word, were quite removed from the teenage sensibility of a high school girl.

To embrace the new genre not just with her voice but also with all her heart, it was essential to understand and empathize with the content of the songs. So began Lee’s research into the songs, which continued through high school and university, and into her years as a training assistant for her teacher, who was a “living human treasure.”

Lee’s studies were enlightening. “You should sing a certain song in a major key, as brightly as the sun in May; another song ruefully like a minor-key song in Western music; yet another song merrily and cheerfully like folk songs; and still another in a big-hearted way,” she says. “I’ve done research on the 12 gasa songs, appreciating the beauty and uniqueness of each, and refined my performance of them for 40 years. Doing so, I realized that the universe is ruled by yin and yang, just as there is no joy without sadness.”

With an insight into human life gained by singing these contemplative songs for decades, Lee presents matchless performances, which have been described as “more potent and profound” than those of other artists with the same repertoire. Her recitals have been particularly successful overseas. During a concert tour last spring around Europe - Hamburg and Munich in Germany and Brussels in Belgium - audiences who were hearing these ancient Korean songs for the first time enthusiastically called for encores.

Lee Jun-ah sings the “Plum Blossom Song” with her students. She currently teaches around 50 students to transmit the tradition of gasa singing.

It has been four decades since Lee first learned to sing gasa at the age of 17. In that time she has worked for the National Gugak Center for 35 years, initially as a member of its court music orchestra, then as an advisory committee member, and currently as concertmaster. All these long years, gasa have been a part of her life. Therefore, being the designated holder of a cultural property [Gasa: Important Intangible Cultural Property No. 41] is a recognition by the state and society that she earned with her lifelong dedication, rather than a mere mark of honor or authority.

Full Cycle Performed

“Nobody had ever performed all 12 gasa pieces on stage, so I decided to give it a try. My efforts came to fruition in 1997, when I held the first-ever recital of the complete gasa cycle. Congratulations and words of encouragement arrived from everywhere,” Lee says. Her songs were released in an album of four CDs in 2008.

In 1997, she also participated in the First International Music Festival “Sharq Taronalari” (Melodies of the East) in Samarkand, hosted by the government of Uzbekistan and sponsored by UNESCO.

“Since gagok were inscribed on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010, efforts to perform and pass on the songs have been greatly stimulated,” Lee says. “I hope the same will happen with gasa, with more people taking active interest in them, studying them, and looking for ways to have them more widely enjoyed.”

Lee Jun-ah has appeared in numerous concerts both in Korea and abroad to promote traditional Korean vocal music. She has been so busy performing that she has had no time to get sick. Her designation as a state-recognized master in the art of gasa has given her tremendous responsibilities.

“Strangely, gasa is a genre relatively better understood abroad than in Korea,” she says. “We have to try harder to make the songs more familiar to our people. Professional musicians in various fields could learn them for collaborative concerts, and other people for cultural enjoyment and mental health. I will also do my part by ensuring that everybody has access to these elegant, meaningful songs.”