Master embroiderer Choi Yoo-hyeon has worked ceaselessly with needle and thread for seven decades. She is recognized for taking Korean embroidery to a new level with her creative techniques and grand-scale renditions of Buddhist paintings.

Sakyamuni Buddha (detail) from “Buddhas of the Three Worlds.” 257 × 128 cm.

Master embroiderer Choi Yoo-hyeon started toembroidery renditions of Buddhist paintings in the mid1970s. Depicting the Buddhas of the past, present and future, “Buddhas of the Three Worlds” is a masterpiece that took more than 10 years to complete.

Anyone can appreciate the beauty of an exquisite piece of embroidery, but not everyone can endure the toilsome and tedious process of stitchby-stitch work over the seemingly endless hours required for its production. This is especially true for traditional embroidery, which is generally more elaborate in procedure, diversified in technique and expressive of an underlying spirit.

“If embroidery was just hard and tedious for me, how could I have done it all my life? I’ve done it because I love it and enjoy it. I have also hoped to keep the traditional handicraft from disappearing entirely,” Choi said when asked if the work wasn’t too laborious.

She continued, “I’m well over 80 now. When I was young, needlework was a big part of the household chores. Families made their own clothes and prepared bridal linens adorned with hand embroidery. I’m the youngest of seven siblings, and I naturally took up embroidery because that’s what my mother was always doing. I really becameinterested in embroidery when I was praised for a piece I had made for school homework. There was a time when I would embroider for more than 20 hours a day, without even eating or washing.”

Formal Training

At 17, Choi was lucky enough to meet Kwon Su-san, a renowned embroidery artist of the time, and begin formal training. At the time she took up the craft as a profession, traditional Korean embroidery was overshadowed by Japanese-style embroidery, which had been promoted as part of women’s occupational training. Practical skills for everyday items were taught at women’s universities and sewing schools. The teachers were mostly women who had studied in Japan. This tendency continued after national liberation in 1945.

In the 1960s, Choi opened an embroidery institute and also began to study traditional Korean embroidery with the goal of reviving and preserving it. Her initial efforts involved applying traditional designs to household items, such as pillow ends and floor cushions. In time, her interest gradually expanded to rendering traditional paintings in embroidery and further reinterpreting ancient artworks in her own style.

“A good embroiderer needs nimble hands and a good sense of color, of course, but what’s more important is whether one has an eye for design,” Choi said. “You can’tyour own style by simply imitating others. That’s why I’ve designed my own works based on motifs from traditional pottery, landscapes and folk paintings.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, amid a widespread disregard for traditional Korean culture, Choi’s embroidered works and their fresh approach to cultural heritage managed to catch the attention of a growing number of people. Her pieces were especially popular among foreign tourists, but Choi had little interest in selling because she put the development of the craft above immediate economic gains.

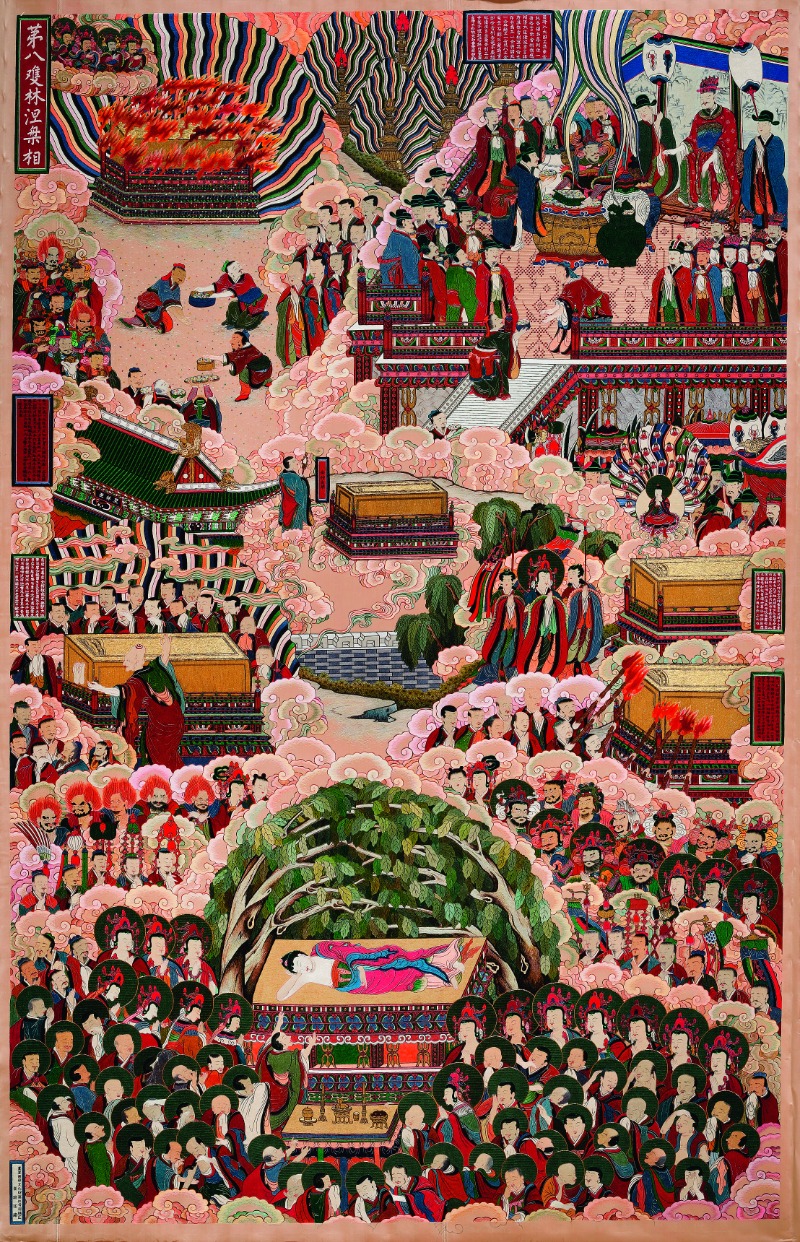

So, in the mid-1970s, she began concentrating on research and exhibitions, working on pieces based on Buddhist paintings, which she believed to be the culmination of traditional Korean art. Her Buddhist-themed masterpieces, representing the pinnacle of her seven-decade career, include “Eight Scenes of Buddha’s Life,” depicting the eight phases of Sakyamuni’s life, and “Buddhas of the Three Worlds,” portraying the Buddhas of the past, present and future. These embroidery paintings, each of which took more than 10 years to finish, are characterized by an exuberant combination of traditional and creative techniques, as well as varied textures resulting from the use of different threads cotton, wool, rayon and silk.

“I put my heart into each and every stitch, working like a monk devoted to spiritual practice,” Choi said. “After I first came across the original painting of the ‘Eight Scenes of Buddha’s Life,’ called Palsangdo, at Tongdo Temple, I prayed and waited for 10 years for an opportunity to re it in embroidery. I finally gained the temple’s permission and began the work, but with each scene measuring over two meters in length, it took 12 years to embroider all eight of them. I worked with my students; otherwise, it would have taken even longer.”

“Lotus Repository World” (detail). 270 × 300 cm.

MFor this embroidery painting based on the mandala at Yongmun Temple in Yecheon, North Gyeongsang Province, Choi was awarded the Presidential Prize at the 1988 Korea Annual Traditional Handicraft Art Exhibition.

Challenges

Her passion and perseverance were rewarded with a prestigious prize; her embroidered version of the “Lotus Repository World,” based on the mandala at YongmunTemple in Yecheon, won the Presidential Prize at the 13th Korea Annual Traditional Handicraft Art Exhibition in 1988. In 1996, Choi was designated as a “living cultural treasure” in the art of embroidery, or National Intangible Cultural Property No.80. This was official recognition that she had reached the highest level of expertisely. Ordinary households also had their own family legacies in the craft.

Choi upholds the idea of “simseon sinchim,” meaning “threads from the heart for stitches of heaven.” Comparing her lifelong work to “heavenly stitches embroidered with her heart’s thread,” this was the title of her exhibition held at Seoul Arts Center in 2016.

She explained, “Every piece is d through a painstaking process. First, I select an original painting, valuable historically and artistically, which can be rendered in embroidery, and then make a sketch on the ground fabric. Once I start embroidering, I have to make one decision after another with the entire picture in mind: the best color and texture for the fabric and the threads, the color scheme, the techniques to use, and so on. As I work, I personally twist my threads to vary their thickness in view of the overall composition and the location of the part in question. I make stitches and remove them over and over until I’m satisfied with the techniques applied and the color tones produced.”

Perfection

“The Great Nirvana in the Sala Grove” from “Eight Scenes of Buddha’s Life.” 236 × 152 cm.

Based on the namesake painting at Tongdo Temple in Yangsan, South Gyeongsang Province, this piece is characterized by elaborate and realistic . Depicting the eight phases of Sakyamui’s life, each scene contains a series of episodes featuring numerous figures on a single canvas.

"Integrity” (detail) from the eightpanel folding screen “Pictorial Ideographs of Confucian Virtues.”128 × 51 cm.

When Choi began studying traditional embroidery in the 1960s, one of her major interests was the reinterpretation of folk paintings, including pictorial ideographs.

Throughout this rigorous process, Choi does everything to perfection. She stresses the importance of being faithful to the basics and following the traditional ways, in order to help transmit the handicraft to the next generations. For this purpose, she has committed herself to teaching as a chair professor at the Pusan National University’s Institute of Traditional Korean Costume.

“Many people realize that traditional embroidery is beautiful and valuable, but very few are willing to learn it, and even those who do mostly give up halfway,” she said. “You need unremitting endurance, even after completing the proper training, to go through the long years of practice before being recognized as an artist. It’s such a thorny path that most don’t even attempt to challenge it.”

She looks back at her life in her memoirs, “History of Choi Yoo-hyeon’s Embroidery,” which will be published soon. The book chronicles her interest as an artisan,shifting from practical household s to folk paintings, and then again to Buddhist paintings. She is also compiling teaching materials for her students. And in addition to her annotated portfolio of over 100 works, published in several books, she is writing yet another book on her original techniques, each with a detailed description and explanation. At the same time, she is in the final stretch of embroidering the “Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara,” based on the mural enshrined in the Hall of Great Light (Daegwangjeon) at Sinheung Temple in Yangsan, South Gyeongsang Province. She has been working on the piece for the past three years, expecting it to be her last grand-scale project. Stitched on purple silk with only golden thread, it gives the impression of reaching the heights of exquisite splendor.

Remaining Mission

“I don’t think I will be able to produce a large piece like this ever again,” Choi said. “I find it hard to work for even two or three hours a day now, because I get tired easily and my eyes get dim. Now it seems to be the time for me to devote my energy to teaching for my remaining mission to pass down as much as I can.”

For almost half a century, Choi has safekept all her works, refusing to sell anything. Along with hundreds of pieces of traditional and modern embroidery she has collected from all over the country, her work is in storage at the National Intangible Heritage Center in Jeonju, North Jeolla Province, with support from the Cultural Heritage Administration. She hopes to see a new museum specializing in embroidery constructed in the near future to preserve and showcase her lifetime collection for as long as possible.

To achieve greater artistry, Choi uses a wide array of techniques, both traditional and original, as well as threads of diverse colors and materials, such as silk, cotton, wool and rayon, todelicate textures.

For the last three years, Choi has been working on the “Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara,” based on the mural in the Hall of Great Light at Sinheung Temple in Yangsan, South Gyeongsang Province. Stitched on purple silk with only golden thread, it radiates with elegance and splendor.