“Korean Video Art from 1970s to 1990s: Time Image Apparatus” at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Gwacheon was a meaningful opportunity to look back on the history of Korean video art. Regrettably, the exhibition was closed for much of its originally scheduled period between November 28, 2019 and May 31, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Video art in Korea developed in tandem with contemporary Western video art, but outside of the world-renowned artist Nam June Paik (1932-2006), the genre remains rather unfamiliar to most Koreans.

“Korean Video Art from 1970s to 1990s” displayed more than 130 works by some 60 artists, spanning from the art’s nascent years to its maturity. The exhibition represented a rare occasion to explore the history of video art and how it took root in Korea, and to appreciate early works from artists who would later attain international repute.

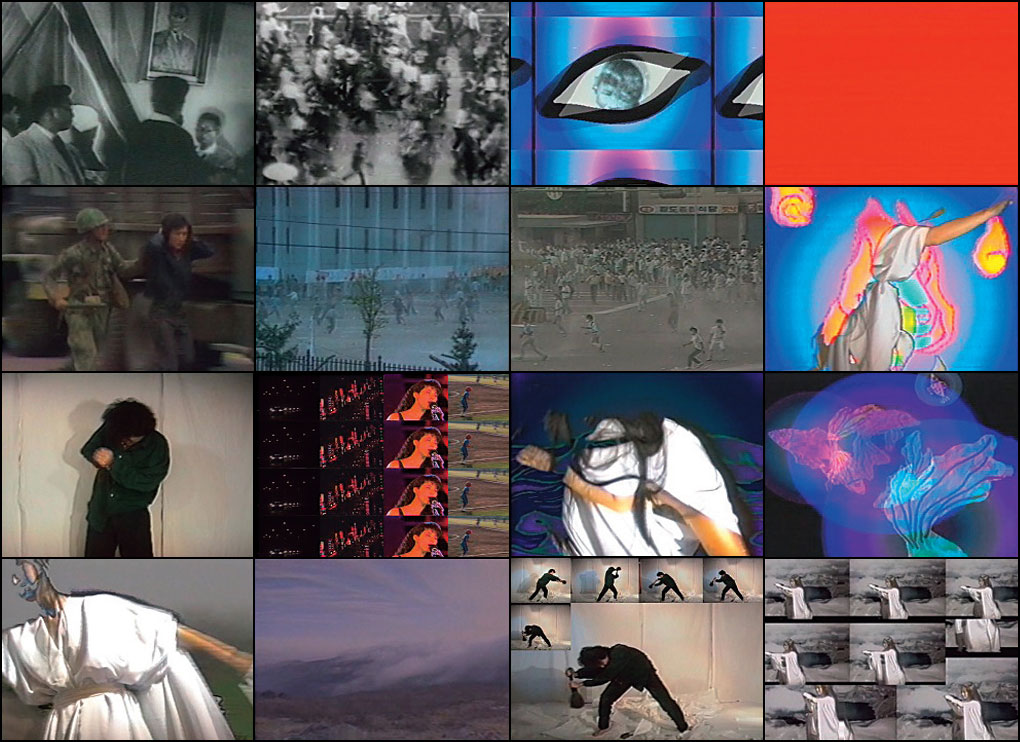

The 1970s were characterized by many experimental and avant-garde movements in contemporary Korean art. Against a backdrop of radical attempts including happenings, installations, photographs and images, a handful of artists conducted pioneering projects in the field of video art. Ironically, the harsh political reality under military dictatorship served to nurture a progressive spirit in the art community.

Avant-Garde Experimentalism

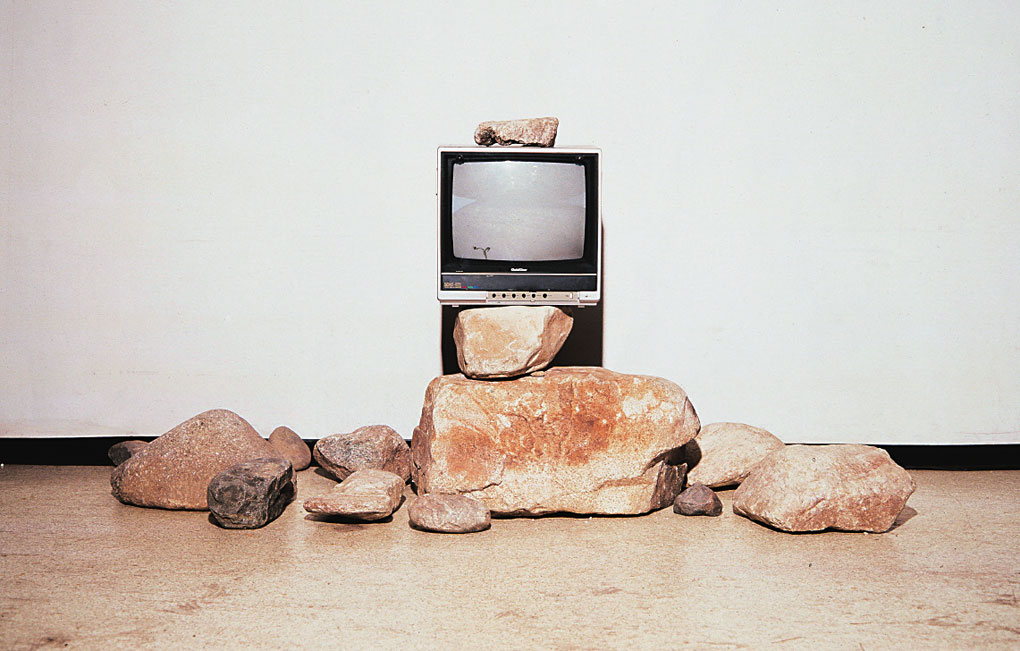

“Untitled” by Park Hyun-ki. 1979. 14 stones, 1 TV monitor. 260 × 120 × 260 cm (WDH). National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

“TV Buddha” by Nam June Paik. 1974/2002. Buddha sculpture, CRT TV, closed-circuit camera, color, silent. Variable size. Nam June Paik Art Center.

Rather than using video as an independent new medium for aesthetic images, most artists embraced it as a tool for practicing avant-garde or conceptual art. At the vanguard of this movement were Kim Ku-lim, Lee Kang-so and Park Hyun-ki. Through the novel medium of video, they began to visualize thoughts about temporality, process and action, sense and existence, and concept and language. For example, Kim Ku-lim’s early work “Wiping Cloth” (1974/2001) condenses the process of wiping a desk with a cloth that gets dirtier and dirtier, almost turning black and disintegrating into pieces in the end.

Fellow video art pioneer Park Hyun-ki began working in the genre around 1973. His “Untitled” series, better known by the nickname “TV Stone Tower,” is a juxtaposition of real stones and video footage of stones – a work that studies the issues of nature and technology, reality and fantasy, and originals and reproductions. Park had been impressed by Korean War refugees who, while evacuating from their homes, took the time to pick up little stones, pile them into small towers and pray in front of them. To him, a stone functioned both as matter and as a cultural-anthropological object projecting human aspirations, and his art offers a glimpse of the relevance of stones in Korean shamanism. Through his work, viewers can see the occult shamanic qualities of traditional Korean art reincarnated with advanced technology.

“Good Morning, Mr. Orwell” is a video art piece edited from Nam June Paik’s satellite installation show of the same name, which aired live across the world on January 1, 1984. This was a pivotal moment that introduced wider Korean audiences to video art. From very early on, Paik took notice of the aesthetic characteristics of light-emitting cathode-ray tubes used in TV sets, distinct from photographic images and movies that are mere shadows. He had originally studied music and had been active in Japan and Germany as an experimental contemporary musician. At the beginning of the 1960s, Paik’s work showed his attempt to arbitrarily manipulate TV in order to break away from the one-way communication of commercial broadcasting. Around 1965, he began employing new video technology in his works, opening a new chapter in media art.

Paik had discovered artistic possibilities in TV. By transforming TV equipment and images, he was able to appropriate the medium for a usage other than its inherent objectives. He thus enabled the fixed medium of TV to take on a formative experiment and incorporate philosophical thinking, ultimately breathing new life into it.

Though not included in this exhibition, “TV Buddha” (1974) is representative of his early meditative and ritualistic art. A monitor is placed on an elongated base facing a bronze Buddha statue, seated cross-legged. A camera placed behind the monitor shoots the front of the Buddha, his visage displayed on the screen, while he calmly gazes at his own image. This installation was acclaimed for combining Eastern religion and Western technology. The Buddha intended to reach the absolute void transcending time and space through meditation, but the image in the monitor shows the body that he cannot shed.

“Heaven, Earth & Man” byOh Kyung-wha. 1990. 16 TVs, video and computer graphics, color and with sound, 27 minutes and4 seconds. Artist’s collection.

Video Sculpture

In the latter half of the 1980s, video sculpture emerged as a new art form. Born out of interest in post-2D, post-genre, mixed media and technology, most of the earliest works consisted of multiple TV monitors piled together or superimposed. After the mid-1990s, however, kinetic video sculpture emerged, combining physical motions and moving images. Among the artists in this group, Kim Hae-min and Yook Tae-jin are in a similar camp with Nam June Paik and Park Hyun-ki in that their work reflects ideological and existential themes.

With profound insight into the medium, Kim Hae-min has created subtle boundaries between virtual and real, past and present, and existence and non-existence. “TV Hammer” (1992/2002), one of his early installations, provides the unique experience of jumping between the real and the virtual with a TV monitor that shakes whenever the hammer shown within hits the screen with a loud bang. Meanwhile, Yook Tae-jin incorporated objects like antique furniture with images of repetitive action, opening up an ingenious realm in video sculpture. In “Ghost Furniture” (1995), two drawers open and shut repeatedly, automated by a motor. Inside the drawers are video images of a man continuously ascending a flight of stairs, reminiscent of humans who, like Sisyphus, struggle toward new heights but are destined to confinement in the absurdity of existence.

It is interesting to see how the supernatural communication and ecstasy inherent in Korean shamanism connect with the up-to-date medium of video. This is one of the most attractive features of Korean video art. The MMCA exhibition served as a reminder of that.

Shamanic Art

“Ghost Furniture” byYook Tae-jin. 1995. 2 monitors, VCR, antique furniture. 85 × 61 × 66 cm (WDH). Daejeon Museum of Art.

Artists are alchemists. They touch and connect trivial materials and turn them into something new. Artists are also shamans who can read the souls of matter. In so doing, they can turn stones and trees into people and they also breathe life into dead matter, turning them into living things. This is not based on human-centered thinking but on respect for all beings as equal. Shamanism is rooted in hylozoism, the philosophical point of view that all matter is alive. The power that animates matter is called god. Shamanism and animism erase all dichotomic divisions and barriers that separate life and death, darkness and light. Shamanism facilitates communication with and travel to the world of death. Similarly, art may be intended to communicate with the dead, show the invisible around us, or allow us to reach the unreachable. Through art, we can therefore escape from a world dominated by that which is visible.

It is interesting to see how the supernatural communication and ecstasy inherent in Korean shamanism connect with the up-to-date medium of video. This is one of the most attractive features of Korean video art. The MMCA exhibition served as a reminder of that.