Contemporary dancer Ahn Eun-me, an iconic figure known for her shaved head and flamboyant costumes, seldom flaunts her past achievements. “Known Future” is a retrospective commemorating the 30th anniversary of Ahn’s debut, set up in multi-purpose spaces where visitors are the main actors participating in various ways. This highly provocative exhibition, opened June 26 at the Seoul Museum of Art, runs through September 29.

Nicknamed the “21st century shaman,” contemporary dancer Ahn Eun-me encourages people with a smile and hugs them, leading them to dance joyously, if only for a moment. She neither criticizes the present with a stern face, nor does she diagnose the future based on pedantic theories. Her works are packed with vibrant colors and lively s. “Known Future,” looking back on her 30-year career, was planned in the same vein. She did not want a conventional retrospective and instead asked for some space inside the art museum.

Exhibition Space Turned Stage

As if it were her persona, Ahn Eun-me’s costume welcomes visitors at the entrance of the exhibition. The costume was worn in a performance for Danish artist Olafur Eliasson’s 2016 exhibition, “The parliament of possibilities.”

In the modernist era, art galleries aspired to be white cubes, but in the 21st century, major galleries are mounting new experiments in the hope of becoming pluralist art spaces. New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), for instance, actively embraces contemporary dance. Now people are saying that museums should become places where the general public can engage in self-motivated learning. In that sense, “Known Future” is right on the mark for it captures the spirit of our times.

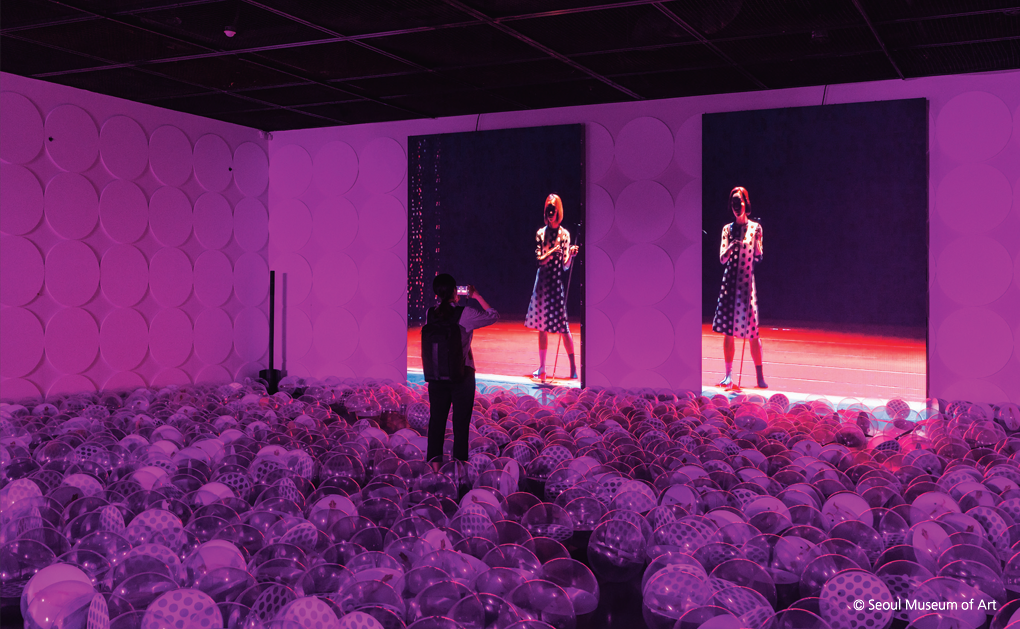

Through spatial variation, the exhibition guides visitors to change their behavior protocol. At the entrance they are greeted with Ahn Eun-me’s costumes hanging from the ceiling. Walking underneath them, they are visually struck by the sensational colors and concurrently experience different textures as the costumes brush against their faces and hair. After passing through the hanging costumes, they come across the lavish gold costume Ahn wore in a performance for Danish artist Olafur Eliasson’s 2016 exhibition, “The parliament of possibilities.” As if it were Ahn Eun-me’s persona, the costume functions as a welcoming gesture. Then, making their way through a beaded curtain, visitors enter a space where the floor is covered with beach balls containing Ahn’s pictures. Text and videos explaining the exhibition, a chronicle of her major performances, and essays and murals illustrating her world of art are splashed across the walls. This is the prelude to the exhibition.

In the next section, many silver air vent tubes are installed like columns, continuously expanding upward and shrinking back. There are wells that present Ahn’s major works on multi-screens and rainbow-colored curtains. Beyond the curtains is a low, wide stage. Stage lights, disco balls, walls covered with circular discs, an actual dressing room, speakers that pour out sound, and two haetae (mythical fire-eating animal) statues adorn the stage.

Titled “This World/World Beyond,” this space is where Ahn Eun-me puts on a series of performances and lectures. “Body Dance” features dance lessons for the audience; “Eye Dance” opens up rehearsals to the public to show how a new work is choreographed and created; and “Mouth Dance” is a series of lectures and discussions. Participating in “Body Dance” and “Mouth Dance” is free for those who have signed up in advance on the museum’s website. The classes by philosopher Slavoj Žižek and installation artist Haegue Yang are impressive, but the museumgoers’ favorite moment is Ahn Eun-me’s body-shaking lesson. They seem to feel a sense of catharsis at rediscovering their own bodies and learning how to use them on a more approachable stage set up in an art gallery.

After the motion-filled “This World/World Beyond,” visitors come across two large screens showing video art. It is a mixture of old and new, ranging from the dance moves of a baby who has just started to take its first steps and grannies’ free-style dance. The core message is the “universality of dance” that Ahn Eun-me has discovered. There is a resemblance in the ways a little baby instinctively moves and an old woman dances with her back and legs bent from years of labor, using her muscles and joints differently from the way she does when working. It is all about escaping reality where you must work to survive, expressing your joy and grief in primitive moves. It is an act of self-esteem; Ahn feels this is the essence of dance.

In the next room is a colorful, squishy Ahn Eun-me style bed, and the original drawings of costumes and a collection of pamphlets are on display with dance music playing in the background. Visitors who just kicked around beach balls in the other room lie down on the bed and spend some time taking selfies or surfing the internet. When the curtain with “good-bye” written on it is pushed aside, the archive catalog marking Ahn’s 30th anniversary, soon to be published, goes round and round in circles bidding farewell.

The low, spacious stage titled “This World/World Beyond,” where many performances and lectures take place, is the most important space in this exhibition.

Abstract Grammar for Dance

Ahn Eun-me made her debut in 1988 as an independent artist. She abandoned the conventions of the Korean dance community, which emphasized beautiful moves following the style and methodology of Western dance. Instead, she introduced non-dance “body speech.” She was not afraid to mix the grammar of traditional Korean dance with that of modern Western dance.

During the 1990s, including her early years in Korea and the time she spent in New York, she experimented with and pioneered the dance language of post-modernism that went beyond phenomenological existence by selecting themes based on social reality, collaborating with artists from different genres, actively using primary colors and objects, and designing stages with visual installations. This period can be summed up as the “Koreanization of post-modernism and post-modernization of Korean dance.”

In the early 2000s, Ahn served as artistic director of the Daegu City Dance Company, presenting aof large-scale works. She introduced a Korean-style dance theater, benchmarking Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater which pursued the recovery of narrative by combining dance and theater.

Ahn did not stop at testing and actualizing her “Vernacular Tanztheater.” In “Let’s Go,” premiered at the 2004 Pina Bausch Festival, Ahn made a breakthrough in methodology. By repeating, adapting and constructing non-dance body movements, she further progressed into the abstract world of modern dance. In a world after post-modernism, William Forsythe and Ahn Eun-me are probably the only choreographers to create their own unique abstract grammar for dance.

Videos showing edited versions of Ahn Eun-me’s works play on two large screens. Visitors can relate to the consistent theme of “universality of dance.”

The museumgoers’ favorite moment is Ahn Eun-me’s body-shaking lesson. They seem to feel a sense of catharsis at rediscovering their own bodies and learning how to use them on a more approachable stage set up in an art gallery.

Universal Body Language

From 2011, Ahn Eun-me challenged herself to study old ladies, youths and middle-aged men as subjects of ethnographic research. It was an experimental move to borrow and recreate their existence on stage. In “Dancing for Grandmother,” Ahn collected the body language people were sharing with her and actually put those everyday people on stage, juxtaposing and mixing them with the choreography she created from her research. “Throughout 25 years of working for the stage, I have been entreating the world and spitting something out. Now I want to do something that’s exactly the opposite,” she said.

Dreaming of “giving dance back to people,” Ahn came to adopt as her medium the art museum which pursues plurality. Under the new conditions of a 21st century art museum, she tries to renew herself, the dancers and the audience. If she keeps trying, then maybe the museum will also be renewed.

Visitors enjoy the opening performance for the exhibition “Known Future,” held June 26 in the lobby of the Seoul Museum of Art.

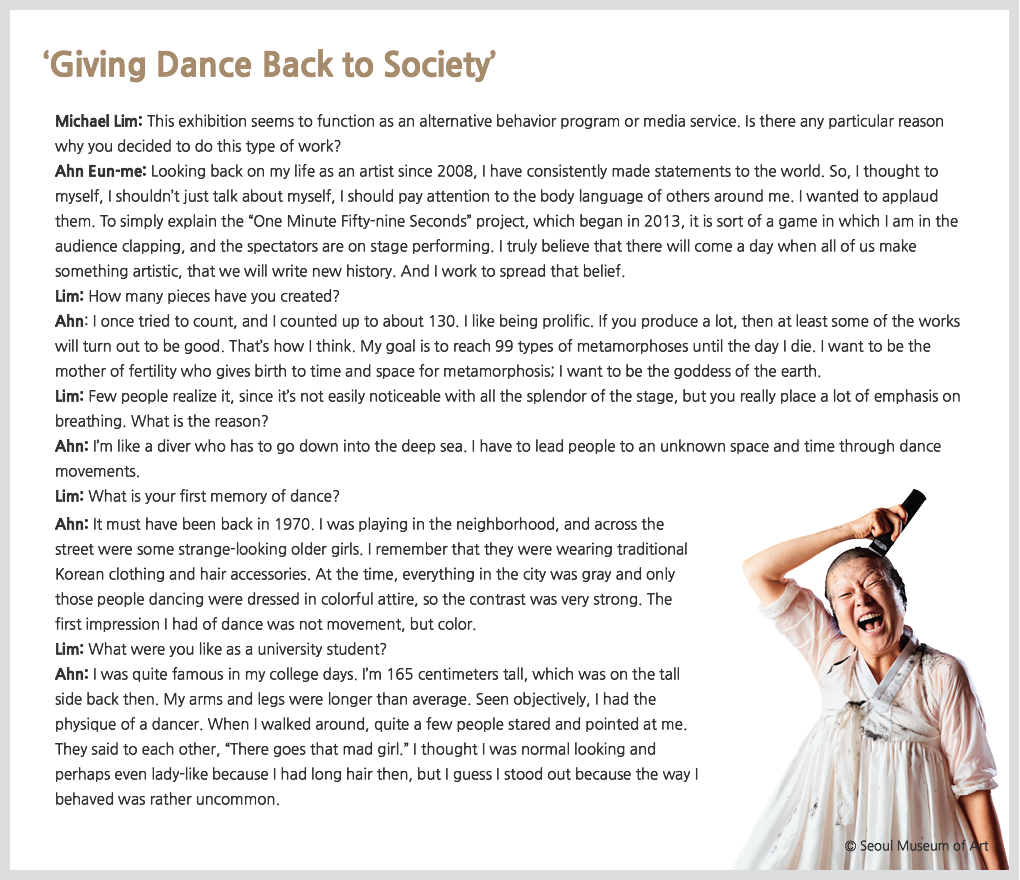

Ahn shaves her head in the picture on the poster for “Known Future,” a retrospective commemorating the contemporary dancer’s 30th year as an artist.

Michael LimArt and Design Historian