Installation artist Choi Jeong-hwa isn’t particularly pleased about being called an “artist.” With a self-identity akin to a “designer,” Choi considers flea markets and traditional street markets to be more artistic, in many ways, than any art museum.

Choi Jeong-hwa says he finds more inspiration at flea markets and traditional street markets than in art museums. Using everyday articles available to all, he creates works that break down the barrier between art and daily life.

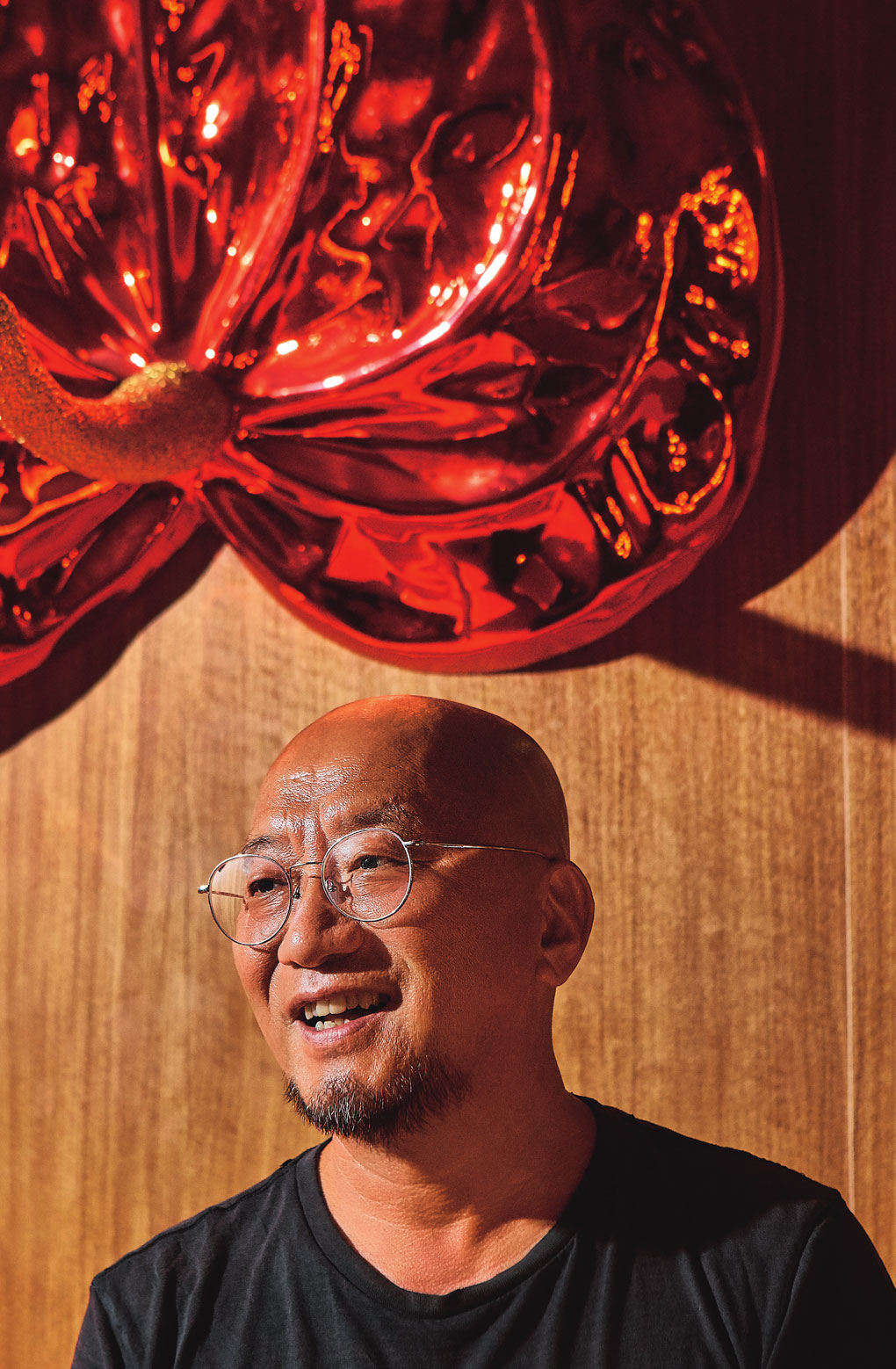

During the week leading up to the Chuseok holiday period, huge balloons depicting a pomegranate, peach and strawberry hovered over the fruit and vegetable market of a provincial city. The balloons, some up to eight meters in diameter, were part of the “Fruit Journey Project” by Choi Jeong-hwa.

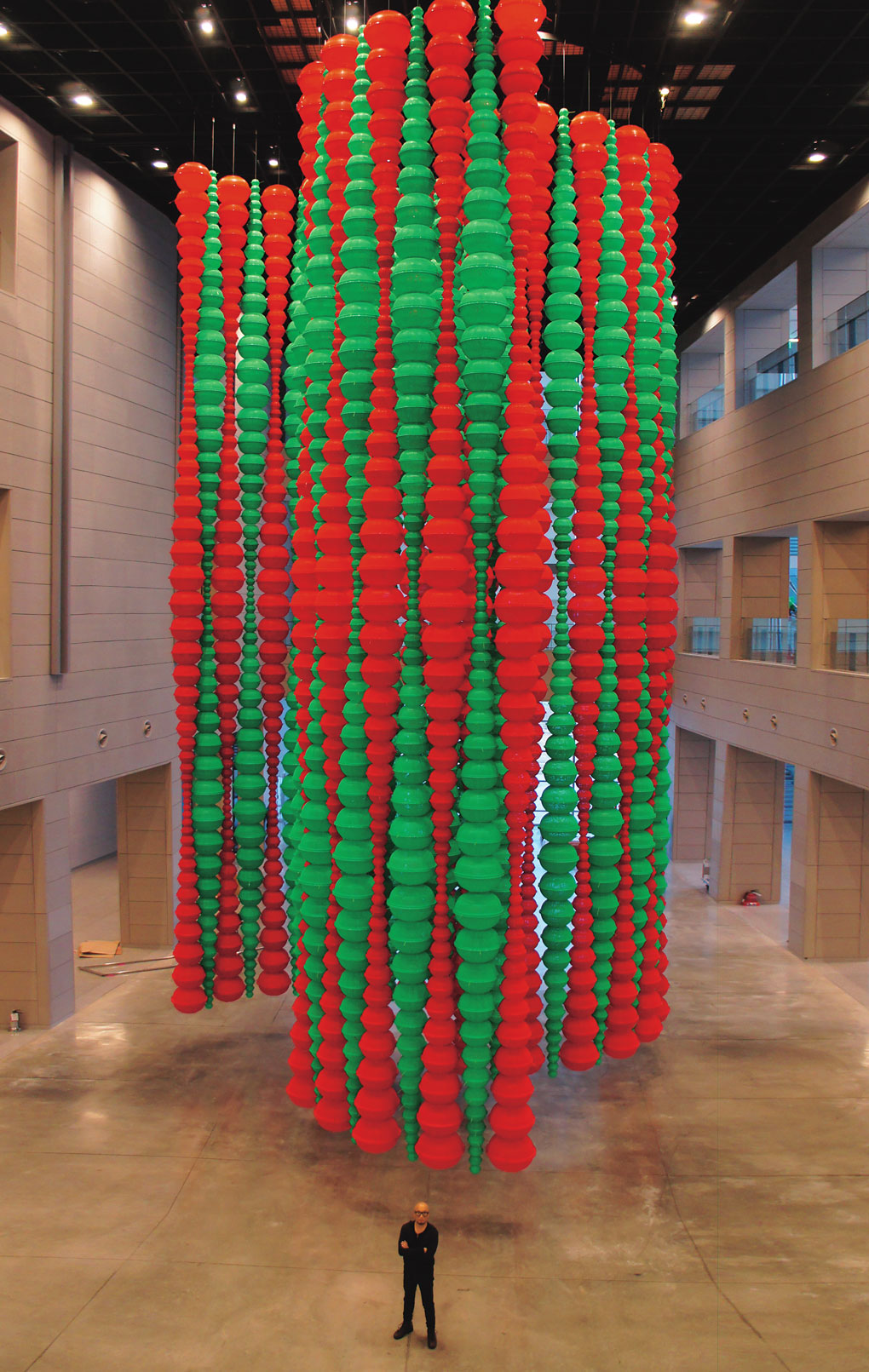

Choi is known for stacking or blowing up ordinary objects that people encounter daily and presenting the reconstitution in a public space. For “CHOIJEONGHWA – Blooming Matrix,” his 2018 solo show at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Choi gathered some 7,000 pieces of kitchenware donated by the public to build “Dandelion,” a piece that ultimately stood nine meters tall. In 2020, he displayed his 2013 work “Kabbala,” constructed of 5,376 stacked red and green plastic baskets, at the Daegu Art Museum.

These methods recall Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” or Claes Oldenburg’s giant sculptures. The major difference is that the components – plastic baskets and kitchen pots – feel familiar to Koreans in particular. The loud colors and familiar materials can’t help but be eye-catching; although passers-by may not recognize Choi’s name, they will remember his artwork. This active master of “Korean pop art” both at home and abroad can be found at his studio in Jongno District, Seoul.

How did stacking begin?

In the early 1990s, I had a solo show called “Plastic Paradise,” in which I stacked green baskets into a bunch of towers. It was an experiment intended to make the familiar unfamiliar. It started from a simple, playful thought: “How will people react if I take these plastic baskets and put them in an art museum’s gallery space?” But in the end, a lot of people loved it.

“Kabbala.” 2013. Plastic baskets, metal frame, variable installation (16m). Daegu Art Museum. Some 5,000 plastic baskets are stacked together in this installation piece, an eye-catching repurposing of an ordinary object.

“Fruit Tree: The Air of the Giants at Villette Park.” 2015. FRP, Urethane, metal frame. Variable installation (7m). This piece in La Villette park in Paris reflects the artist’s characteristic fondness for kitsch and animation. Variations on this piece, with the same title of “Fruit Tree,” have been installed in several other places around the world.

Why plastic baskets, of all things?

Originally, I painted. I even won a few awards. But I felt some doubt about it all. So for some three years, I declined invitations to exhibit. Then, the moment I decided to finally accept one again, I was struck by a red plastic basket that happened to be lying around my house.

Some say you ended up using everyday materials as a way to avoid exercising artistic stunts.

The methods and subjects I tend to choose are usually about making play and an installation outdoors. “WITH” was the title of the 2015 solo show I had at the Onyang Folk Museum. I collected furniture from abandoned houses near the museum and built a tower of dinner tables, among other things. These are attempts at a kind of play that occurs beyond what we consider visual art or fine art. Because you really run the risk of becoming, you know, “A League of Their Own.” I put it this way: I want to make a “playground where life becomes art.” Then anyone can enjoy it, recalling past images and memories all their own. Art, fundamentally, belongs to everyone – and it was a grievance of mine that only this specific category of people, this one percent, were getting to enjoy it.

In truth, even now, contemporary art doesn’t come easily to me. There’s a lot I don’t understand. So just imagine what it must be like for the general public.

That’s very honest.

It’s the truth. I said as much not long ago, at a solo show I had at Gallery P21. I said, “This exhibition is basically a Choi Jeong-hwa product show, a bujeok (talisman) show.” What I mean is that anything an artist makes is ultimately a product.

Do you mean you consider communication to be important?

I suppose I do, in the end. It’s my belief that one shouldn’t be aiming to reach the experts. The first time I exhibited [the stacked baskets] the cleaning lady saw it and said to me, “What pretty baskets! Give me one, too.” That, to me, is a sign that this mode of communication I’ve attempted is working.

You’ve also been very active in art direction for both stage and screen, not to mention interior design.

I’ve done some boutiques and clubs, some bar interiors. Then, along the way, I met modern dancer and choreographer Ahn Eun-me and ended up doing some stage art for her. Then I met poet and novelist Jang Jeong-il and began working as an art director for the film adaptation of his work, “301 302” (1995). This movie was about two women who lived as neighbors in the same apartment building, one suffering from anorexia and the other from compulsive overeating. I started off intending to work on just the art, but eventually I offered to take on the full role and work on all aspects of creating the film’s overall atmosphere.

Honestly it was even before this, in the late 1980s, that I worked at an interior design firm – and even founded a firm of my own. The things I did back then were “blindingly insignificant” things. In an ordinary boutique, I would use some unusual material or just leave the debris in place after demolition. They were “meticulously loose” things, too, you could say. My experience with material and space during that period shaped everything that came after it.

“Cosmos.” 2015. Beads, mirror sheets, metal wire, clips. Variable installation (Top); “The Mandala of Flowers.” 2015. Plastic caps. Variable installation. This project was unveiled at “APT8 Kids,” part of the 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT8), held at the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) in Australia. Plastic chains and colorful s of beads dangled from the ceiling while children played freely with countless plastic caps.

What about your “Alchemy” series? Do you mean it as a prayer for luck?

Well, alchemy is literally alchemy – the practice of turning base metal into gold. It assigns meaning, turning these plastic pillars I make into something more. Creating gold might be impossible, but this is a process that transforms matter into mind. When you watch shopkeepers at the market stacking their wares, you can’t help but gasp – not just because of the aesthetic beauty but because of the incredible skill, the years of practice you can feel. It’s the beauty of the sublime, found in these countless piles of plastic.

Why do you stress praying for good luck?

You know, I’m not sure. Maybe because we didn’t have much when I was growing up? We were dirt poor, and between first and sixth grade I transferred schools eight times. So, I don’t actually have any childhood memories. It’s total darkness, a blank. And you know, there’s nothing as frightening as having no memory of something. I think I came to use those years. I didn’t have any friends to play with because we moved so often, so I developed a habit of picking up trash and discarded objects on my own. When I became a university student, I would often find myself incredibly moved on my walk to and from school. There were junkyards and construction sites on my route, you see. One time I even stumbled across a hunk of gold. But then once I got to school, I felt stymied – it was like I couldn’t hear or think clearly. Maybe this is why, but artists who know me well tend to say my works are very sad.

It may be a dangerous thought, for something to be “for everyone,” but my art was made in the streets. When art was something high up and out of reach, I wanted to say, “Come down and play,” to insist “art is what’s right beside you.”

“Cabbage and Cart.” 2017. Silicone, cart. WDH: 210 × 100 × 106 cm. Silicone cabbages are stacked in a cart that rests at one end of the gallery. This is part of the “Sarori Saroriratta” exhibition at Gyeongnam Art Museum (October 22, 2020-February 14, 2021).

“A Feast of Flowers.” 2015. WDH: 122 × 75.5 × 290 cm. Part of the exhibition “WITH: Choi Jeong-hwa & Onyang Folk Museum” at the Onyang Folk Museum’s Gujeong Art Center (March 31-June 30, 2015). Kitchen goods like small tables, trays and dishes from homes near the Onyang Folk Museum in Asan, South Chungcheong Province, form a nine-story pagoda.

Your work seems to be influenced by your mother.

My father was against me going to art school. He even broke my brushes to keep me from painting, so I entered the design department of Gyeonggi Technical College [now Seoul National University of Science and Technology]. It was my mother who helped me secretly so that I could apply to art school. When we couldn’t pay the studio fees, she would even bring kimchi to the studio instead. My mother is my creator and my goddess. And she is actually quite talented herself, too.

You now have a show at the Gyeongnam Art Museum?

Well, 50- to 70-year-old handcarts from the local fruit and vegetable market enter the museum to become works of art. Colorful parasols from the market are transformed into a chandelier, and a boat abandoned along the coast also makes an appearance. Most important, though, is that we’re also inviting local urban revitalization activists as guest artists to introduce their own projects, too.

Any plans for future projects?

It may be a dangerous thought, for something to be “for everyone,” but my art was made in the streets. When art was something high up and out of reach, I wanted to say, “Come down and play,” to insist “art is what’s right beside you.” Currently, I’m very interested in “regeneration.” I’m considering how to execute a return to the source, the root of all.