Lee Jung-sung was running an electronics shop in Seoul in 1988 when he first met Nam June Paik, the father of video art. For nearly two decades thereafter, Lee worked as Paik’s project technician and main collaborator. Lee is still busy these days overseeing the late virtuoso’s legacy, restoring and maintaining his works.

Lee Jung-sung, installation engineer for video artist Nam June Paik, poses in front of “M200” exhibited at the Tri-Bowl in the Songdo Central Park, Incheon, in 2010. The 1991 work is a video wall comprised of 94 monitors. It is 3.3m wide and 9.6m tall. © News Bank

Behind Nam June Paik, the world’s first video artist, there was Lee Jung-sung. Their first collaborative work was a tower of 1,003 TV sets titled “The More the Better” (Dadaikseon, 1988). In the ensuing 18 years, Lee engineered the installation of Paik’s artworks, and as they crisscrossed the globe, Lee morphed into Paik’s closest collaborator and source of ideas. It could be said that Nam June Paik’s brain soared on the wings of Lee Jung-sung’s hands, and Lee Jung-sung’s hands were able to build amazing things because of Nam June Paik’s brain.

Nowadays, Lee occupies a sixth-floor studio in Sewoon Sangga, a neighborhood by Seoul’s Cheonggye Stream and the parallel walkway that slices through the downtown Jongno District. His desk is at the end of a long space with shelves lined with old TVs, electronic parts and books about Nam June Paik. The hands that fitted “The More the Better” shook mine warmly.

Sowing Trust

Lim Hee-yun: When did you start working here in Sewoon Sangga?

Lee Jung-sung: Construction was completed on this market complex in 1968, but I’d been in the neighborhood since 1961. Back then, there were stores and workshops selling junk and electronic parts huddled together in temporary buildings lined up all the way from out the front of Jongmyo (Royal Ancestral Shrine) down to Toegyero. The very start of my work with electronics was a vacuum tube radio one of my older brothers had when we lived in Busan.

Lim: From one radio to all those TVs? When did you come to Seoul?

Lee: I was young and really obsessed with my brother’s radio. I’d hide it under the covers and keep it on all night while I slept. We couldn’t afford to keep buying new batteries. My brother always scolded me for using them up. That radio was so magical to me that in the end I started opening it up and looking at all the parts. I really got a taste for it, so I said to my family, “This is what I’ll have to study.” My older sister lived in Seoul then. I told her, “I don’t mind if I have to sleep in the doorway, please just keep me fed and dry,” and so I ended up staying with her. I must have been around 18 when I started attending the Gukje TV Institute at Euljiro 2-ga. After studying at the institute, I came into Sewoon Sangga and got work. At that time, regular households didn’t have TVs. It was before the KBS television station even existed. Households with money to spare would buy a TV to watch the American military broadcasts. I started out installing and fixing these TVs.

Lim: So how did you meet Nam June Paik?

Lee: I have to set the scene first. The household appliances trade show in Korea began in 1986. The Seoul International Trade Fair opened in what is now the COEX Convention Centre in Samseong-dong, and the competition between Samsung and LG was really intense. They were having a battle of ideas, under strictest secrecy, to come up with the most innovative display for the grand opening. The Samsung side commissioned me to install a “TV wall.” I managed to build a wall of 528 TVs in little time, so after that they got me to do all the displays for the major Samsung Electronics stores in Seoul.

And then it was 1988. Mr. Paik was asking around for a technician to help build “The More the Better,” and eventually got in touch with me because I was doing that work for Samsung. He asked me, “Can you do me one with 1,003?” And, of course, I said, “Yes, I can do that.” I was thinking, “I did one with 528, just doubling the number shouldn’t mean it can’t be done.” At that point I had no idea about what an important figure Nam June Paik was, or what an embarrassment it would be on the global stage if we couldn’t pull it off. They say, don’t they, that you’re bravest when you know nothing.

Lim: Did the work on “The More the Better” go smoothly?

Lee: Mr. Paik tasked me with installing the 1,003 TVs and then he went off to America, simply saying, “Do a good job.” At the time, the biggest challenge to installing TVs on such a large scale was how to deal with the video feed. Even in Japan, they only had a device that could distribute video to six TVs simultaneously. And it was 500 dollars apiece, which was a lot of money. So I started making my own from scratch. In the end, the 1,003 TVs worked perfectly by the promised date of the live broadcast. It was the best feeling ever. I think Mr. Paik was really surprised, too. Later on, when he came back to Korea, he admitted to me, “To be honest, I thought if even half of them worked, it would be a big achievement.” Then he asked, “I have to make another work in New York. Could you do it?” And I responded, “Sure, yeah, why not?” The work was “Fin de Siècle II,” which was installed at the Whitney Museum in 1989.

After that one, Mr. Paik sent me to Switzerland where I couldn’t even speak the language. I had to install 80 TVs in a week, and because of my massive bag full of TV parts and tools, I was stopped by customs at Zurich Airport. I wrangled with the customs officer, speaking in Korean and making signs with my hands and feet. I managed to persuade the gallery to extend the time I was able to work until after closing. I finished the work in less than five days and was able to go off and do some sightseeing. That was when Mr. Paik really came to believe in my grit and adaptability.

Exchange of Ideas

In this 1994 photo, Nam June Paik and Lee Jung-sung test an early version of “Megatron/Matrix” at Paik’s Seoul office.

Lim: Nam June Paik was an artist and you’re a technician. Were there any communication problems when it came to your work?

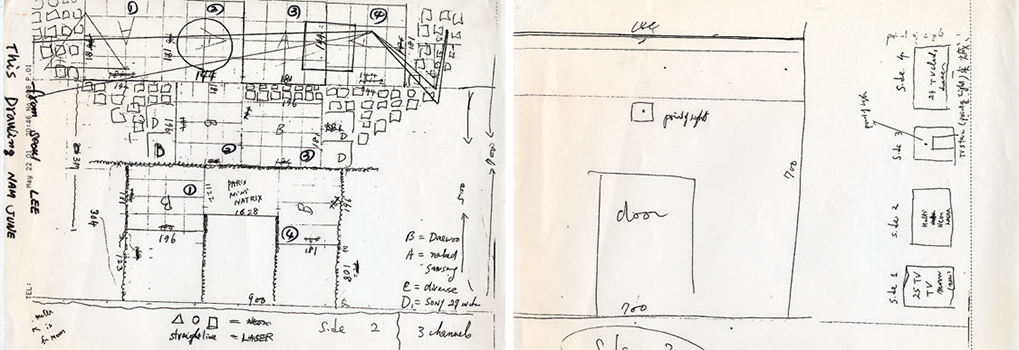

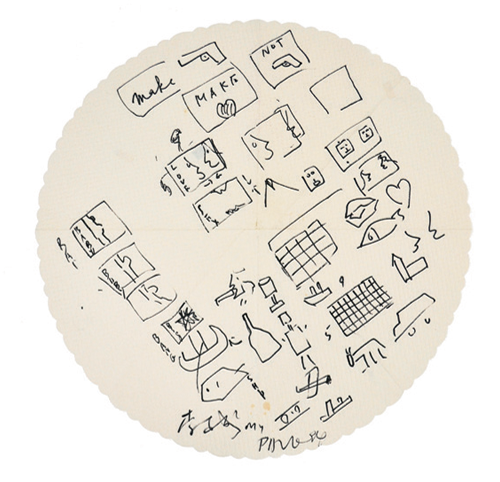

Lee: When I worked with Mr. Paik, we never needed to use anything like an official blueprint. We spent a lot of time together in restaurants and cafés. Wherever we went in the world, we’d sit for hours on end discussing things and sketching ideas on restaurant napkins and paper tablecloths. Sometimes we even drew on record sleeves and cigarette papers. The scribbled diagrams and explanations were almost like the random digit tables you see spies using in the movies, but it was fine because I was the only one who needed to understand them.

Quite a lot of artworks started out with Mr. Paik saying: “Remember the thing we talked about at the café in France? Shall we have a go at that?” “The thing we chatted about in New York, let’s try it out!” The idea for “Megatron/Matrix” (1995) that included animated images with video displays came about like that.

A diagram for Nam June Paik’s works submitted to the 1993 Venice Biennale. Paik represented Germany at the biennial art exhibition and received the Golden Lion.

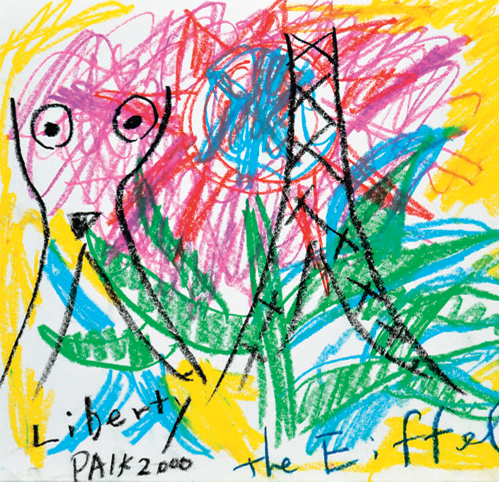

A drawing made by Nam June Paik as a gift for Lee Jung-sung.

The concept outline for “Megatron/Matrix” (1995) drawn by Nam June Paik on a paper tablecloth at a café near Montparnasse Station in Paris. The first “Megatron/Matrix” is owned by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., the second by the Seoul Museum of Art, and the third by the Seoul Olympic Museum of Art.

One day, an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris had just ended and there was a reception. The two of us concocted a story to tell the president of the center that we weren’t feeling well and left. We went straight to a café near Montparnasse Station and sat down at the best spot in the whole place. From our table, there was a direct view of what was then the biggest neon advertising display in Europe. The two of us sat looking out the window and came up with the plan for that artwork.

Lim: You started out as a technician. How were you able to understand the creative world of Nam June Paik when even people in the art world at the time weren’t able to keep up with him?

Lee: I’ll turn that question around. Do you understand Picasso’s paintings? There’s no right answer when it comes to appreciating works of art. There’s nothing to wonder about with why people like a certain artwork either. You just need to feel for yourself, “That’s fun,” or “That looks good.” At the beginning, I also just passively made whatever Mr. Paik instructed me to make. But from some point or other, I started candidly proposing my ideas, too. If I were to say, “I think it would be good if we add something like this, what do you think?” he’d respond with, “Hey, buster, you should have said so from the beginning.” And then I realized, “Ah, if I suggest my ideas in advance, he really would take them on.” Yes, he would readily take on the advice I gave in consideration of the environment of the exhibition space and technological limitations.

“Tower” (2001) exhibited at “LETTRES DU VOYANT: Joseph Beuys x Nam June Paik” held at the HOW Art Museum, Shanghai, in 2018. Lee Jung-sung spent two weeks for installing Paik’s works for the exhibition. Courtesy of Lee Jung-sung

Lim: It’s been a long time since the TVs of “The More the Better” could operate at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, Gyeonggi Province. With conflicting opinions in the art world about restoration methods, the situation seems to have come to a standstill.

Lee: There are a number of different ways of doing it. The first method would be to replace the TVs with Braun tube screens. But it’s a very difficult option to put into practice, because it’s a pyramid that’s 19 meters tall. It would be a huge undertaking just to put up the support beams and scaffold. The method that I’m in favor of would be to replace the old Braun tubes with LCD screens. But it clashes with the opinion that flat-screen LCDs would ruin the curved lines of the Braun tube sets that are in the original. I don’t agree. When it comes to media art, isn’t the spirit of the artist in the software, not the hardware? “Seoul Rhapsody” (2001) at the Seoul Museum of Art was made with flat screens. When Mr. Paik made “The More the Better,” he didn’t use Braun tube sets because he liked them. It was because that was all there was at the time, so he couldn’t help but use them. And so I can’t agree with the opinion that replacing them would be damaging the original.

Based on that logic, you have to be opposed to the restoration of paintings, too. With Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” in the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, what only remained as an outline was painted again over a number of years. In that case, would it also be right to say that it shouldn’t have been touched? I once asked Mr. Paik when he was alive, “What do we do if the TVs break down?” And he simply said, “When that happens, we’ll just replace them with ones that work.” If he saw the situation right now, I’m sure he’d have a good giggle about it. In some circles people are even hinting that it should just be taken apart all together. But if we do that, in the long run, we’d end up being a laughingstock in the international community.

Lim: Is there a lot involved to maintain Nam June Paik’s works? And what work do you do now aside from that?

Lee: Not long ago, I worked on restoring the work “108 Agonies” (1998) in Gyeongju. It was so damaged that it took me a whole week, and I also did some work on “Fractal Turtleship” (1993) at the Daejeon Museum of Art. Recently, I went over to the Whitney Museum in New York to help with the conservation of “Fin de Siècle II.” Aside from that, I give advice to young budding artists, and I occasionally give lectures, too. This autumn, there’s a big Nam June Paik retrospective in Nanjing, China, and I think I’ll have to work on that one, too. I also have to keep pouring my heart and soul into the organization of his archive.

I once asked Mr. Paik when he was alive,

“What do we do if the TVs break down?”

And he simply said,

“When that happens, we’ll just replace them with ones that work.”

Preservation and Restoration

Lim: Now the era of YouTube is in full swing. How do you look back on Nam June Paik’s art in this day and age?

Lee: He went around piling up debts toinnovative artworks, but with today’s technology he would have made loads of really unusual works. In his later years, he stopped doing video art and tried to go into laser art, but the overheads were just so high. He was just about able to use military-grade lasers. If lasers and LED had been in use when Mr. Paik was doing his work, we probably would have gotten to discover another Nam June Paik, entirely different from the one we know.

Lim: Do you still sometimes think of the days when you were working with Nam June Paik?

Lee: Of course. I was nothing but a technician, but since I worked with Mr. Paik on his artworks, I got to travel the world and wanted for nothing. To tell you the truth, even now, once or twice a month, I meet him in my dreams and we work together. It’s completely new work. In the dreams, we never work again on the works we made in the past. Maybe his insistence on always going after what’s new is still alive.

Lee Jung-sung at his studio, located in Sewoon Sangga, a shopping, industrial and residential complex in central Seoul. His studio is filled with old TVs and electronic parts he has collected. Lee says that once or twice a month these days, he still has a dream in which he works with Nam June Paik.