Wearing a cap and overalls that he designed, Lee Kwang-ho seems to be envisioning himself as an astronaut traveling in space. “Dreaming is what I do, and so I’m the happiest when I’m able to turn my dreams into reality, and my thoughts into results,” says the young designer. His eccentric but delightful works, d with everyday materials, a simple approach and meticulous handcraft, have garnered recognition in the international art world.

“Osulloc Tea House” (Detail),

Seoul, Lee Kwang-ho, Collaboration with Grav, 2017; Electric wire.

Lee Kwang-ho’s first break came like a miracle. The first exhibition he held after completing his studies in metal art and design at Hongik University went largely unnoticed. He was extremely disappointed and frustrated when it didn’t receive any reviews, good or bad. Hearing of this, a senior alumnus told him about an overseas website where designers could promote their work. Lee put together a portfolio of his works and posted it on the site. He was desperate, but also confident. Although he had never studied abroad, he firmly believed that his steadfast and sincere commitment to the exploration of materials and handcraft would be noticed.

“Not long after, I was contacted by Les Commissaires in Montreal, Canada,” Lee said. “With high hopes, I immediately flew over there. I met with Pierre Laramée, the gallery’s director and co-owner, who said he was impressed with my work and proposed a solo exhibition. I asked what it was about my work that appealed to him, and he said that it was ‘original and special.’ My first private exhibition held at the gallery in 2008 was well-received, and my works also sold well. This opened up further opportunities. The Johnson Trading Gallery in New York and the Victor Hunt Gallery in Brussels expressed interest in my work, and I was invited to sample fairs and major international art fairs including Design Miami/ and Art Basel.”

The fact that his works caught the discerning eye of the Johnson Trading Gallery, a leading p in New York’s design and art scene, was instrumental in allowing the then largely unknown Korean designer to successfully enter the global art scene. From then on, it was smooth sailing for Lee. He was flooded with requests for collaborations from galleries based in leading design cities, such as Berlin, Paris, London, Amsterdam and Milan. In April 2009, he was selected as one of the 10 emerging designers to watch in a major event at the Milan Furniture Fair (Salone Internazionale del Mobile di Milano), earning global recognition.

Redefining Ordinary Materials

“A simple approach has been the key concept of my works. The lighting design class I took in college was the beginning,” said Lee. “While other students thought that all there was to designing light fixtures was varying the shades covering the light bulbs and thus limited themselves to changing just their shapes or materials, I tried to come up with ways tosomething out of the box using the basic elements of electricity, electric wires and light bulbs. So, I decided to weave the electric wires. That’s how my ‘Knot’ and ‘Obsession’ series were d.”

Lee has a talent for rethinking the familiar materials we come across in our daily lives. He allows us to rediscover their aesthetic beauty by creating s through his technique of manually intertwining materials like electric wires, garden hoses and PVC tubes that can be found lying around a house. The interwoven electric wires hanging from the ceiling are beautiful in their rawness and the “aesthetics of the weave.” The harmony d by the juxtaposition of mass-produced industrial materials and knitting is delightful and humorous. For some, the work evokes images of a fishing lamp on a boat and for others, of knitwork.

“I remember my mother knitting sweaters and mufflers for me when I was young,” Lee recalled. “I was amazed at the patterns and textures she d with the colorful wool. Thinking back to those days, I weave each strand with utmost care. I believe that good design boils down to fine details. Ultimately, it depends on elaborate detail and artistic completeness. I myself have striven toward a state of perfection until I add the final finishing touches, which I could say is why I have been able to continue to present my works on the international art stage. I need to stay focused.”

Lee recalled memories of his grandparents’ farm in Cheongpyeong, Gyeonggi Province, which he visited as a child. He remembers having learned to use his hands while helping his grandparents during school holidays. His grandfather’s hands seemed magical in the eyes of a young boy. He was awed at the sight of his grandfather fashioning a broom simply bya bunch of bush clover branches and stacking bundles of harvested crops. He realized then that design is the process of ordinary, crude materials being transformed through a person’s hands. Memories of his grandfather and his childhood days spent in the countryside have been a source of inspiration for his handcraft projects.

“I remember my mother knitting sweaters and mufflers for me when I was young. I was amazed at the patterns and textures she d with the colorful wool. Thinking back to those days, I weave each strand with utmost care.”

Design That Harbors Many Stories

“The collaborative project with fashion brand Fendi titled ‘Fatto a Mano for the Future’ in March 2011 was an opportunity for me to reconfirm my belief in working with my hands,” Lee said. “Sitting side by side with a Fendi craftsman and weaving the leather s, I realized anew that the precise repetitiveness involved in twining together s, whatever the material, must have been the future of mankind for a long time. The intense beauty of the weave is sure to deeply impress any viewer. This simple act is good for passing the time and clearing your mind. Once anstarts to take shape, it stimulates your imagination to go on to the next stage of the creative process.”

The “ramyeon chair” featured in Lee’s “Obsession” series, so called because of its resemblance to curly instant noodles, is a big hit in any gallery around the world. Children rush to it as soon as they see it, and touch and sit on it. It’s not simply a piece of furniture; it becomes a playground. The distinguishing feature and philosophy of Lee’s design is flexibility: his works kindle the viewers’ imagination, inspiring them to think of different uses for the . He likes tofurniture harboring many stories that vary depending on the space.

“Design is like storytelling,” said Lee. “I attached the title ‘Shape of a River’ to a piece I made by corroding copper. Usually, a title will spring to my mind while I’m working. I start simple, but gradually the work expands. This whole process is interesting. As these stages are repeated, it eventually results in a good design.”

Last year, Lee converted a three-story row house into an art studio. Like his designs, it has a simple beauty, displaying a neat interior decorated with metallic materials while preserving the original form of the old brick building. The location is ideal since it is near the factories that are essential for his work. For more than 10 years, he has been working with the same plastic processing companies and welders who understand his concept. They are like-minded friends who support his unfamiliar endeavors, and at times, even pitch ideas.

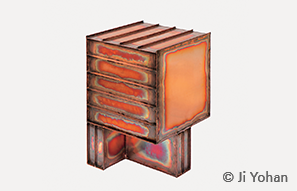

“Obsession” Series, Lee Kwang-ho, 2010; PVC

“Osulloc 1979” (Detail), Seoul, Lee Kwang-ho, Collaboration with Grav, 2017; Granite, enamel, copper, aluminum, stainless steel, Styrofoam, glass, and wood

Lee has worked on collaborations with many brands, including Christian Dior, Swarovski, Onitsuka Tiger and Gentle Monster, through his company “k L o” (Kwangho Lee Office). The scope of his collaborative projects has expanded remarkably. In the past, he mainly received offers from fashion brands that saw a similarity between his handicraft technique and the method of weaving fashion fabrics, but now he also receives commissions from hotels and large businesses.

AmorePacific’s new headquarters building is one such project Lee has collaborated on. Designed by English architect David Chipperfield, the building that was completed this year features an unconventional spatial composition where Lee’s design can be witnessed in every corner. The well-structured spacious lobby welcomes visitors, who can comfortably relax in the red, blue, yellow, green and brown chairs and sofas from Lee’s “Obsession” series. Lee also designed the space for the Osulloc Tea House and the brand’s premium tea room, Osulloc 1979, as well as the furniture, lighting and fixtures, which have been favorably received by customers. The interior gives the feel of relaxing and drinking tea in a natural environment, inside a huge forest or cave.

“I used granite because I liked the compressed grains visible on the surface. It is a material with potential for diverse uses,” said Lee. “The AmorePacific project is particularly memorable because I was able to use the different properties, textures and weight of stones toworks of various shapes and functions, applying them to the space.

“Shape of a River” Series, Lee Kwang-ho, 2017; Copper

In a large-scale project like that, the artistic completeness of small elements is all the more important. I considered the spatial configuration of the large building, but I realized that in the end, my perfectionism would be the key and solution. I intend to keep forging ahead faithfully, accumulating experience in working with materials I haven’t used before.”

In 2017, Lee was once again in the global spotlight when he was awarded Designer of the Year at Mercado Arte Design (MADE), a design and art fair in Sao Paolo, Brazil. He plans to hold a solo exhibition later this year at Salon 94 in New York. Flooded with proposals for collaborations, the busy designer said humbly, “I chose a great profession and I was lucky.”