A published collection of interviews with senior pro-North Korean artists residing in Japan provides valuable insight into North Korean music and how its distinguishing characteristics have been formed.

A scene from “The Song of Mount Kumgang,” one of North Korea’s five major revolutionary operas. Premiered in 1973, it tells a story of family members separated during the colonial period and then reunited under the socialist system led by Kim Il-sung. The picture is from a 1974 performance by the Kumgangsan Opera Troupe, which was founded in 1955 under the pro-Pyongyang General Association of Korean Residents in Japan.

While the native music of North and South Korea have the same roots, they no longer share the same harmony. What is called gugak in the South is minjok eumak in the North, both meaning “national music” but with different connotations. The two sides even differ in their use of traditional musical instruments. The South focuses on preserving the original form of these instruments, while the North crafts variations that can also be used to play Western music.

“A Collection of Oral Recounts by Senior Overseas Korean Artists – Japan” parts the curtain on the development and current state of music in the communist North. The weighty volume, illustrated with rare historical photos, was published in December last year by the National Gugak Center, a Seoul-based public institution for preserving and promoting traditional Korean music.

“North Korea has outdistanced South Korea in terms of the endeavor to modernize traditional musical instruments and try their hands at fusion music,” said Cheon Hyeon-sik, curator at the National Gugak Center and co-author of the book along with Kim Ji-eun, a researcher of North Korean music.

The North’s effort at modernizing native Korean musical instruments has turned the 12- zither, the gayageum, into an instrument with 19 or 21 s. It has also changed the tone scale of traditional Korean music from pentatonic to heptatonic scales. Some modernized instruments of the North have been accepted by South Korean performers. They include the okryugum, a 33-ed zither; the jangsaenap, an oboe-type, double-reed wind instrument; and the daepiri, a clarinet-like brass instrument.

The co-authors spent three years conducting interviews and compiling the book. “The interviewees unanimously said that it’s impossible to discuss music apart from politics in the North,” they explained. “It has also been reaffirmed that music has greater influence than any other art genre there.” This is based on the background of the late leader Kim Jong-il’s instruction: “Music should serve politics. Music without politics is like a flower without fragrance. Politics without music is like politics without a heart.” Thus, music in the North has come to have a different face from music in the South, where it largely plays a part in each individual’s pleasure and taste.

Interviewees

The poster for “The Flower Girl,” a revolutionary opera that toured China in 2008. Some 50 Meritorious Artists and People’s Artists performed in the production, alongside members of the Sea of Blood Theatrical Troupe. © Yonhap News Agency

Cheon Hyeon-sik (left) and Kim Ji-eun, co-authors of “A Collection of Oral Recounts by Senior Overseas Korean Artists – Japan.” The book is based on interviews with eight prominent musicians and dancers residing in Japan.

The book’s eight senior artists residing in Japan – all of them recipients of North Korea’s People’s Artist, Meritorious Artist, People’s Actor, or Meritorious Actor awards, and recognized as supreme authorities in their respective fields – were interviewed between 2017 and 2018. Two passed away while the book was being compiled.

The interviewees were: Im Chu-ja (1936-2019), choreographer and dancer; Lee Chor-u (1938- ), composer and deputy director of the Isang Yun Music Institute in Pyongyang; Jung Ho-wol (1941- ), singer and former actress of the Kumgangsan Opera Troupe; Kim Kyong-hwa (1946-2017), former conductor of the Kumgangsan Opera Troupe; Hyun Gye-gwang (1947- ), dancer; Ryu Jon-hyon (1950- ), opera singer; Jong Sang-jin (1958- ), composer; and Choi Jin-uk (1958- ), professor of music education at Korea University Tokyo.

Composer Jong Sang-jin said most of his North Korean cohorts compose “program music,” primarily based on Russian-influenced melodic motifs, staying away from Western “melodic fragments,” be they symphonies or smaller orchestral works. However, Jong noted that there is slightly more diversification these days, and works with more melodic fragments than before are being written.

Co-author Cheon provides complementary interpretations to better explain the different aspects of music in the two Koreas. For example, he cites the operas of both Koreas based on the ancient folk tale of Chunhyang. North Korea’s folk operas emerged along with the state’s effort to modernize traditional musical instruments in the 1960s. The genre began there with “The Tale of Chunhyang” and went on to yield revolutionary operas in the 1970s.

The North Korean opera version of the tale showcases the Western bel canto technique for beautiful singing, instead of Korea’s traditional raspy vocal style of pansori (narrative song). It also highlights class struggle, a sharp contrast to the Southern version, which sticks to the original plot of a love story between an aristocratic boy and a lowborn girl that leads to a happy ending.

“North Koreans learn pansori as a mere subject of study, no longer enjoying it as a genre of folk music,” Cheon said. Pansori has been rejected by the socialist regime in the North largely on the grounds that it is permeated by upper-class values, while in the South it has gained remarkable popularity as a representative traditional music genre.

Vocals

In the North, vocal music has undergone changes in techniques, lyrics and even musical forms. In other words, it has been transformed to suit the goals of the North’s socialist revolution and its people’s sensibilities.

Two vocal techniques in particular are emphasized: “minseong” for the traditional vocal genre and “yangseong” for Western classical music. The former is also called “juche style,” referring to a clear and lilting style rooted in the traditional seodo (western province) style of singing. “The Tale of Chunhyang” features singers performing in the traditional folk style, whereas “The Flower Girl,” a revolutionary opera, highlights those singing in the Western style.

Singer-actress Jung Ho-wol said North Koreans prefer high voices. They believe that native folk songs should be sung in a thin, high-pitched tone. But they have come to love songs sung in low voices as well, as many mezzo sopranos have come on stage these days.

“According to Mr. Jong Sang-jin, each of the outstanding North Korean operas has its own characteristics,” Kim Ji-eun said. “For example, ‘Sea of Blood’ gives off a nationalistic and folksy feel; ‘The Flower Girl’ presents many refined melodies; and ‘The Song of Mount Kumgang’ has a very modern touch.”

These characteristics also stand out in the orchestral arrangements. “Sea of Blood” was written with a focus on purely native instruments. The orchestra for “The Flower Girl” initially featured native instruments and Western brass instruments, later adding violins for overseas presentations. And the orchestra for “The Song of Mount Kumgang” only consists of western instruments, with the sole exception of bamboo wind instruments.

The interviewees largely agreed that national music has lost its charm in the North, in comparison to the Western music that appeals to young people nowadays.

Winds of Change

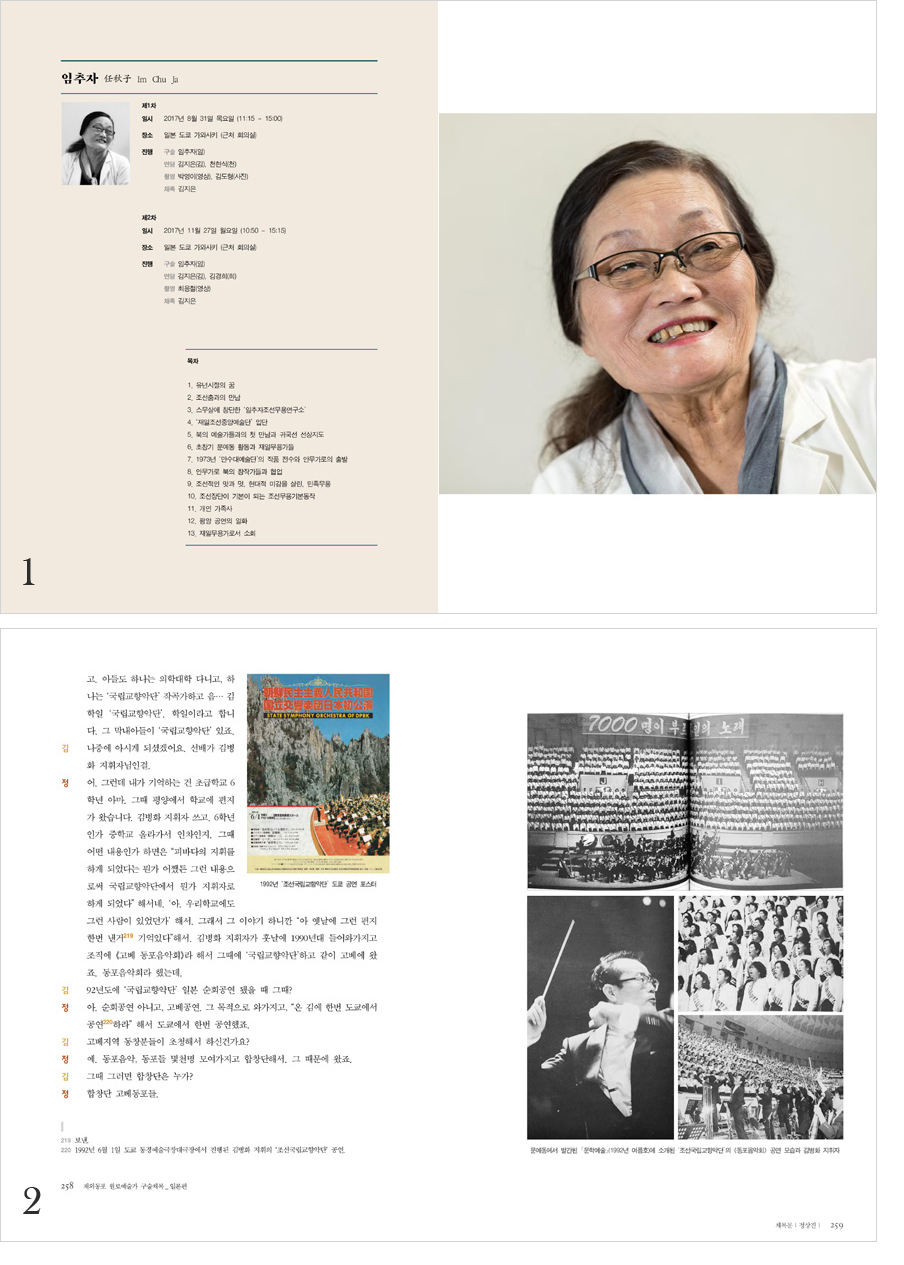

1.Biographical data of choreographer and dancer Im Chu-ja. She dedicated herself to teaching students after establishing the Korea Dance Institute in 1957, earning a reputation as a “great star” in the dance world of Korean residents in Japan. She passed away in 2019.

2.Jong Sang-jin, a composer, recalls the life of Kim Byong-hwa, conductor of the State Symphony Orchestra of North Korea. Photos of Kim and the orchestra’s concert in 1992 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre are shown on the right-hand page.

The interviewees largely agreed that national music has lost its charm in the North, in comparison to the Western music that appeals to young people nowadays, Kim Ji-eun noted. For example, the Samjiyon Band, which mostly performs European classical music, enjoys great popularity, and its concerts that feature conductor Jang Ryong-sik attract even larger audiences. The band drew significant interest when it visited the South to give concerts in celebration of the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang.

Kim recalled the interviewees’ claims that the North’s music scene is undergoing changes in step with overseas trends, introducing a variety of new vocal techniques. “Mr. Jong Sang-jin further said that North Korean music colleges these days mainly teach three types of techniques, following the performing style of the Moranbong Band; that is, the techniques for native folk songs, Western classical music and contemporary pop music.”

Currently, the members of the Moranbong Band, known in the South as a “North Korean girl group,” are the most popular artists among North Koreans. The band was launched in 2012, shortly after Kim Jong-un came to power. Its leader Hyon Song-wol aroused much attention from the South Korean media and public during the band’s visit for the 2018 Winter Olympics.

Most of the band members are graduates of either Pyongyang University of Music and Dance or Kum Song Music School. The latter is the alma mater of the North’s First Lady Ri Sol-ju. This has sparked speculation that she was the one who initiated the band. Both the Moranbong Band and the Korean People’s Army State Merited Chorus are regarded as icons of the Kim Jong-un era. Their performance style exerts strong influence on other performing arts organizations in the country.

Isang Yun (or Yun I-sang, 1917-1995), a South Korean-born composer who was charged with acts of espionage for North Korea in 1967, is highly esteemed in the North, whereas he has not received a proper evaluation in the South. The Isang Yun Music Institute in Pyongyang and its Isang Yun Orchestra remain active today. “There are many people in Pyongyang who are crazy about Yun’s music,” Cheon quoted the interviewees as saying.

Elements of jazz and rock are also increasingly seeping into North Korean music. Regime founder Kim Il-sung once forbid and demonized the genres, saying, “Western pop singers take drugs and lead dirty lives.” No doubt the carefree lifestyles of many musicians were of little help in dissuading the authorities in Pyongyang. But the interviewees agreed with Kim Ji-eun’s view that swing rhythm and jazz beats seem to have been integrated into North Korean music today.

Kim Hak-soonJournalist; Visiting Professor, School of Media and Communication, Korea University