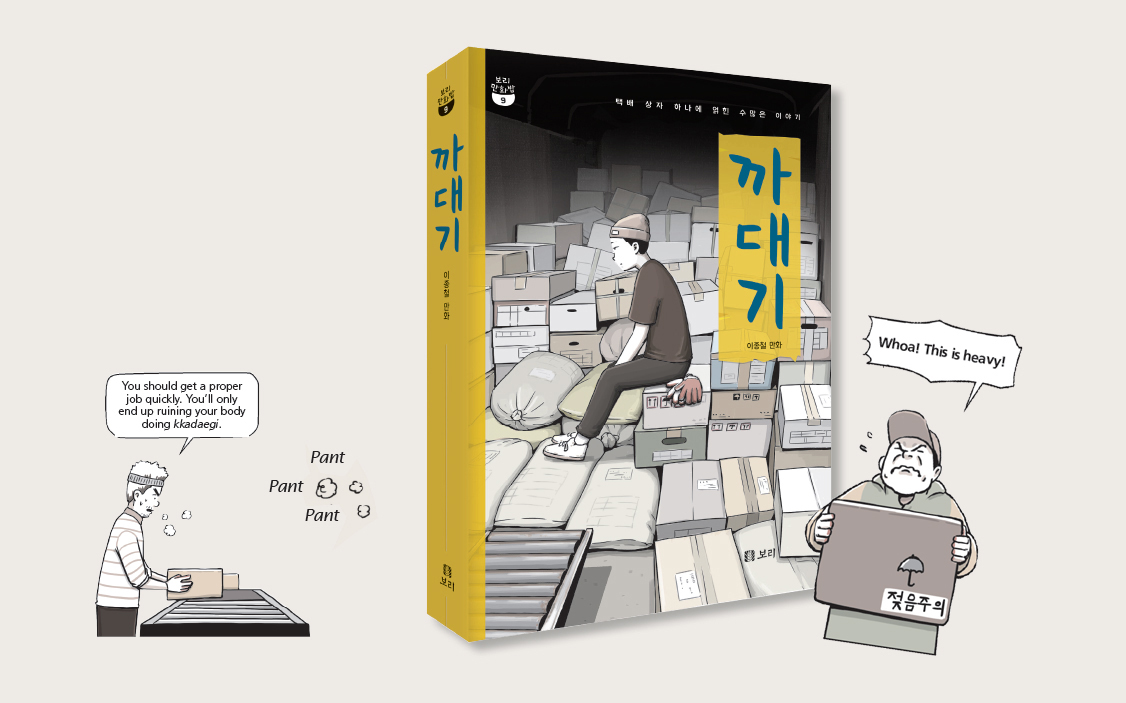

Products ordered online pass through many hands before they are delivered to the customer. Unloading packages from heavily loaded trucks is one part of the process. Comic artist Lee Jong-chul portrays his own experiences as a package unloader and episodes about his colleagues in the comic book “Kkadaegi,” published in 2019.

Igraduated from an art college in the provinces and came to Seoul with my mind set on achieving my childhood dream of becoming a comic artist, but with no specific plans. My parents supported me financially for a while, but the money they sent wasn’t nearly enough to live on in a city like Seoul. I needed to earn a living while working towards my debut as a comic artist. Ideally, I would work for five to six hours and draw comics the rest of the day. An opening for a morning-shift loading and unloading job caught my eye. Wouldn’t it be too strenuous? I hesitated for a bit, but the work site was near my place and the pay was higher than the minimum hourly wage, which enticed me to call. The person on the other end asked if I could start the next day. I said that I could. That was how I began my part-time gig as a delivery truck unloader.

“On the Way to Market in Snow.” Presumably Yi Hyeong-rok (1808-?). 19th century. Ink and light color on paper. 38.8 x 28.2cm. National Museum of Korea. This Joseon Dynasty painting depicts merchants heading for the market with their wares loaded on the backs of horses and oxen. It is part of an album allegedly painted by court artist Yi Hyeong-rok. © National Museum of Korea

First Part-Time Job

Online purchases go through several stages before they arrive at the customer’s door. First, the seller confirms the orders and packages the items, then a person from the partner delivery company takes the packages to the warehouse. The packages are loaded onto trucks and taken to the delivery company’s central distribution center, where they are sorted overnight according to postal code. Part-time workers load the sorted packages onto trucks, which take them to regional distribution centers at around dawn. There, the packages are unloaded from the trucks and the delivery drivers take them to the end user.

My first part-time job was at a delivery company’s regional distribution center. On the first day, the manager asked if I had done kkadaegi before. This is industry jargon for loading and unloading items from trucks. I told him I had no experience whatsoever. He introduced me to another part-timer who would work with me as a team: a man in his mid-50s with graying hair. He was brusque but explained to me in detail, step by step, what I would be doing. He only asked me my surname. Due to the grueling nature of the job, there was a high turnover, so he didn’t bother to ask my full name. He called me Lee and I called him Mr. Woo.

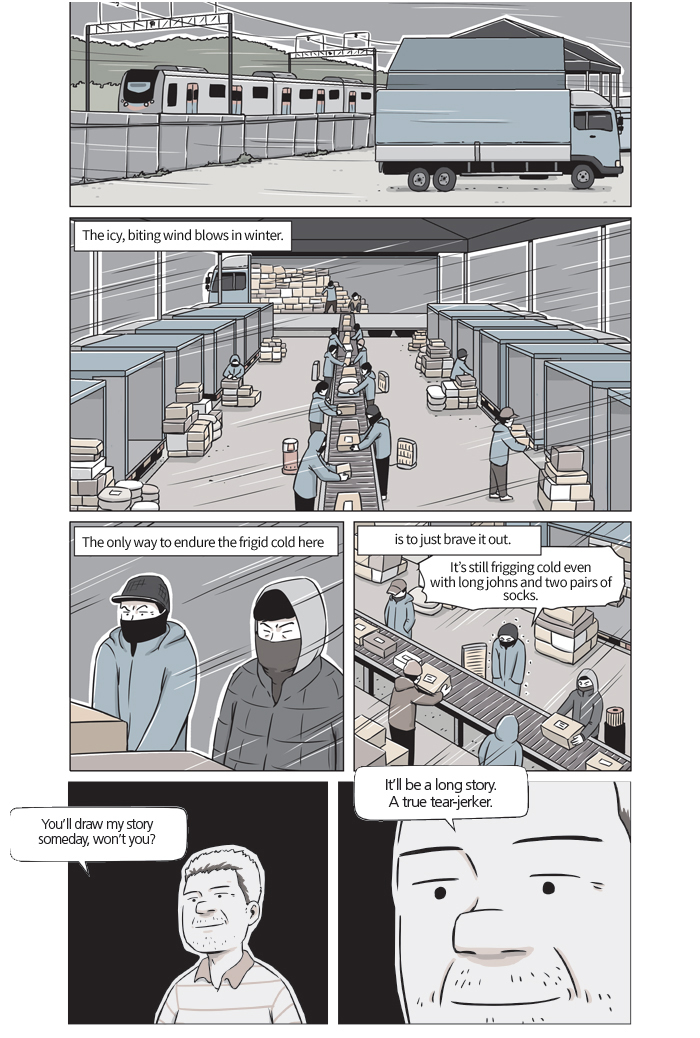

I met people from all walks of life: an athlete who used to be goalie in the K3 League; a guy studying for the national police exam; a semiconductor factory worker who married young and wanted to provide better for his family; a middle-aged man who worked 30 years in civil service; and our captain in his mid-40s who lived with a sick mother. Everyone had their own story.

‘Cans’ and Lower Back Braces

Our job was to unload the boxes from the trucks and place them on a conveyor belt. Delivery drivers stood waiting by the conveyor to take the packages for their respective zones. An 11-ton truck can carry an average of 700-800 packages, occasionally holding more than 1,000. We worked in teams of two to unload on average four to five trucks a day. It took about 40-50 minutes to unload each truck. After just one truck, my legs would feel weak and wobbly. The trucks, called “cans,” were poorly ventilated and stuffy; as soon as I started work, the dust immediately stung my nose and throat, and I began sweating like a pig. I realized why the pay was 2,000-3,000 won higher than the minimum hourly wage. I started at 7 a.m. and finished past lunchtime. Only then did the drivers set off to deliver the packages to eagerly waiting customers.

Over time, I became friends with the drivers. They generally worked from 7 a.m. until late in the evening, and way past midnight during peak seasons when demand surged. They earned a modest fee of less than 1,000 won per delivery. The deliverymen wanted us to work faster so they could head out quickly, while we wanted to take intermittent breaks; such opposing stances bred conflict at times.

Workspaces at distribution centers are usually located outdoors, leaving workers exposed to the elements. We had to brave sweltering heat and frigid cold. The so-called “delivery crisis” repeats every year around the Chuseok holidays in autumn. That’s the peak delivery season, when box upon box of newly harvested rice and other crops, salted napa cabbage for kimchi, and ready-made kimchi fill the distribution center. We got through it by wearing a lower back brace.

Mr. Woo eventually quit and went to work at an agro-fishery market on the outskirts of Seoul, carrying vegetables at night. I also quit and went to work with him. One day, a publisher contacted me with a proposal for a children’s comic series. When I told Mr. Woo the good news, he leapt for joy and told me never to come back to that place. I promised I wouldn’t. However, I soon found drawing comics didn’t earn me enough to get by, so I resumed my side gig at another delivery company. But I didn’t tell him. “There was this young friend called Lee Jong-chul who worked with me for a while. He plugged away at his comics and achieved his dream of becoming a comic artist.” That’s how I wanted him to remember me.

The work was even more exhausting than I had expected, but there were upsides. I got to meet people from all walks of life: an athlete who used to play goalie in the K3 League; a guy studying for the national police exam; an employee at a semiconductor factory who married young and wanted to better provide for his family; a middle-aged man who had retired after 30 years in civil service; and our captain in his mid-40s who lived with a sick mother. Everyone had their own story.

Unlike older generations, digital natives born after 1980 effortlessly adapted to the latest technologies, and in no time, advanced delivery services became a distinctive feature of Korean society.

We worked in teams of two to unload on average four to five trucks a day. It took about 40-50 minutes to unload each truck.

Everyone Has a Story

I grew closer to my colleagues as time went by, and I wanted to put their stories into comics. So I began writing down my experiences at work. I wanted to tell their stories, console them and root for them. The culmination was my comic book “Kkadaegi,” which came out last year.

During these trying times, when the whole world is reeling from a pandemic, the delivery industry has been receiving renewed attention. On the flip side of the convenience of getting anything, anytime, anywhere without face-to-face interaction are miserable incidents of overworked couriers collapsing due to explosive growth in delivery volume. Delivery packages have various warning labels attached to them: “Don’t throw,” “This side up,” “Fragile,” and so on. One day, it occurred to me that these precautions shouldn’t just apply to delivery boxes. These days when I meet people, I tell them, “Handle your body and mind with care!”

Lee Jong-chulComic Artist